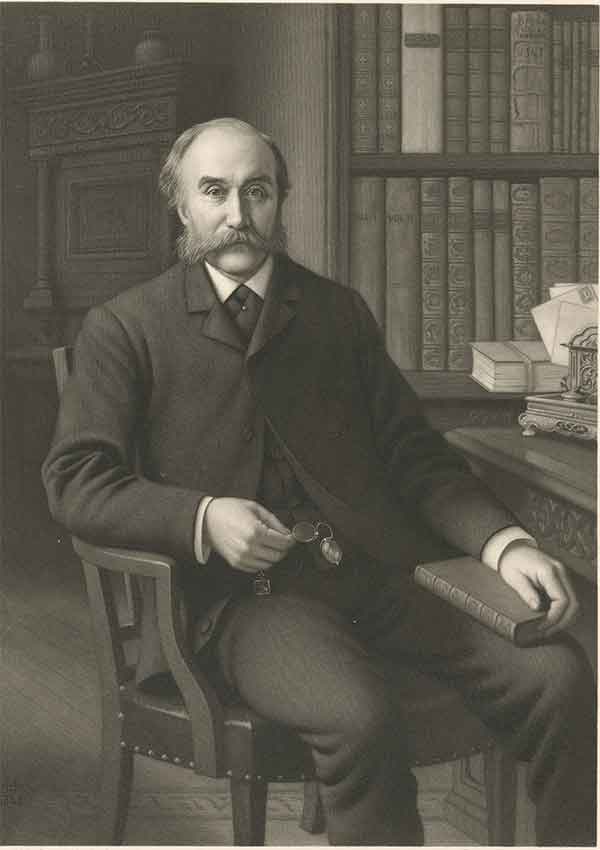

Thomas Addis Emmet

The sub-headings for navigation purposes have been added to the original entry. The image has been borrowed from an external source. Thomas Addis Emmet’s line of descent can be found in the Emmet family genealogy which is part of John O’Hart’s Irish Pedigrees.

Emmet, Thomas Addis, M.D., Barrister-at-law, a leading United Irishman, son of Dr. Robert Emmet, State Physician, was born in Cork, 24th April 1764.

Education

He was educated at the school of Mr. Kerr, and entered Trinity College in 1778.

His career there gave ample promise of future eminence.

Upon taking out his degree he proceeded to Edinburgh, where he devoted himself with ardour to medical studies, and formed lasting friendships with Sir James Mackintosh and Dugald Stewart.

He was at one time the president of no fewer than five societies—literary, scientific, and medical—formed among his fellow-students.

Death of Temple Emmet

He remained in Edinburgh the winter after his graduation, visited some of the principal schools of medicine in Great Britain, and afterwards travelled through Germany, France, and Italy.

On his way home, news reached him of the death of his elder brother Temple, a young barrister of great promise.

Admitted to the Irish Bar

At his father’s desire, and by the advice of Mackintosh, he immediately relinquished medicine, read for two years at the Temple, and was admitted to the Irish Bar in Michaelmas Term, 1790.

Marriage

The following year he married Jane, daughter of the Rev. John Patten of Clonmel.

Defence of James Napper Tandy

The first case in which he distinguished himself was that of J. Napper Tandy against the Viceroy (the Earl of Westmoreland) and others, in which the validity of the Lord-Lieutenant’s patent was contested, as having been granted under the great seal of England instead of under the Irish seal.

Leonard McNally was one of Emmet’s fellow-counsel, and there is every reason to believe betrayed all the pleadings to the Government.

Emmet’s speech attracted considerable attention, and a full report of the proceedings at the trial was published by the Society of United Irishmen.

United Irishmen

In September 1793 we find Emmet associated with the Sheareses and McNally, in the defence of a Mr. O’Driscoll, tried for seditious libel at the Cork assizes.

In 1795 he appeared as counsel for persons charged with administering the United Irish oath, and to confirm his argument in favour of its legality, solemnly took it himself in open court.

The next year, 1796, he began to take a prominent and leading part as a United Irishman.

Possessed of private means, already earning £750 a year at the Bar, with a young family rising up round him, of domestic habits and irreproachable character, nothing but the clearest convictions of duty could have impelled him to range himself against the Government.

Already, in 1792, he had joined the Catholic Committee, and Tone speaks of him as “the best of all the friends to Catholic Emancipation” except himself.

In this service he had made no public display.

The meeting with Russell and Tone, prior to the departure of the latter for America, took place at Emmet’s house near Rathfarnham in 1795.

In 1794 the Society was forcibly broken up; in the beginning of 1795 it was reorganized as a secret society, and in 1796 the military organization was engrafted on the civil.

Upon O’Connor’s arrest in 1797, Emmet took his place on the Directory.

FitzGerald, O’Connor, and Jackson urged immediate action.

Emmet, McCormick, and McNevin advocated the policy of waiting for French assistance.

Emmet afterwards admitted that this dependence on French assistance was ultimately fatal, and that Bonaparte was the “worst enemy Ireland ever had.”

The Government, having allowed the plans of the Society to reach sufficient maturity, availed themselves of the services of Reynolds, the informer, and on the 12th March 1798 the deputies were arrested at Oliver Bond’s, in Bridge-street.

Emmet and others were taken at their houses, examined at the Castle, and after a few days committed to Newgate.

There was no specific charge against Emmet, but he was rightly regarded as one of the most formidable opponents of the Government.

Soon after his committal, his wife managed to visit him, and with the connivance of the jailers, and through her own determination and firmness, she was permitted to reside with him during the whole term of his incarceration of twelve months in Newgate and Kilmainham.

1798 Rebellion

Meanwhile, during the summer, abortive risings took place in different parts of the country, and after the engagements of Antrim, Ballinahinch, and Vinegar Hill in June, and the capitulation of Ovidstown on the 12th July, all hopes from insurrection were over.

Blood now flowed in torrents, and with a view to arrest the slaughter, Emmet and other State-prisoners entered into an agreement with the Government, by which they bound themselves to disclose all the workings and plans of the association, without implicating persons, upon condition that the Government should stop the executions, and allow him and his companions to leave the country.

Examination before Parliamentary Committees

Emmet’s examination before Parliamentary Committees took place in August.

He defended the policy of the United Irishmen, and showed that revolution was inevitable after the rejection of the moderate demands of the Irish people for reform in Parliament—demands that embraced Church disestablishment, Catholic emancipation, a national system of education, freedom of commerce, and a reform of the criminal code.

In the course of his observations, he remarked:

“I have no doubt that if they [the United Irishmen] could flatter themselves that the object next their hearts would be accomplished peaceably by a reform, they would prefer it infinitely to a revolution and republic.”

The gradual improvement of the condition of the people, in spite of evils complained of, being urged, he declared it was “post hoc sed non ex hoc.”

A study of these examinations will show the nature of the early claims of the United Irishmen, and on the other hand, how convinced Castlereagh and the Government were that the concession of reform was incompatible with “constitutional government.”

Fort George prison

The Government, it is said, published a garbled report of these examinations; the State prisoners replied by advertisement in some of the papers.

Upon the plea that this was a breach of faith, and in consequence of the objections of Rufus King, the American Minister in London, to the deportation of rebels to the United States, the Government altered its intentions (according to Emmet’s account, broke faith), and on the 26th March 1799, after a year’s imprisonment, Emmet, O’Connor, Neilson, and seventeen companions were embarked in the Aston Smith transport, landed at Gooroch on the 30th March, and imprisoned in Fort George, Inverness-shire.

The governor, Stuart, was a humane man, and did all in his power to alleviate their confinement and mitigate the harsh orders of the Irish executive.

About the close of 1800 Mrs. Emmet was permitted to join her husband, with her three boys, Robert, Thomas, and John.

Their youngest child, Jane Erin, was born in Fort George.

After release

After three years’ confinement, all the prisoners were liberated, and they landed in Holland, 4th July 1802.

From this date, until October 1804, Emmet resided successively at Hamburg, Brussels, Paris, and on other parts of the Continent.

He considered himself absolved from any promise of abstaining from action against the Government.

In the end of September 1803 he received in Paris the news of his brother Robert’s execution, and in the following December he had an interview with Bonaparte, and presented a memorial relative to an Irish expedition.

Under the command of General MacSheehy, the United Irishmen in France formed themselves into a battalion, and prepared to take part in the invasion promised by the First Consul in a communication to Mr. Emmet, dated 13th December 1803.

Their hopes for a time ran high, as active preparations for invasion went forward; but they were doomed to disappointment.

United States

In April 1804 Bonaparte’s plans were changed, and on the 4th October Emmet embarked with all his family at Bordeaux for the United States.

During his residence in France all who were nearest and dearest to him in Ireland had been swept away by death—father, mother, brother, and sister.

His intention after landing was to settle in one of the western States, but friends who knew his abilities opened the way for his appearance at the New York Bar, and there his success and advancement were more rapid than he had dared to hope.

From the first he accepted the States as his adopted country, he seldom referred to the past, and he was happy in his family and in the society of many of his old friends who had settled in New York.

Anti-slavery

His first case was one in which he was employed by some members of the Society of Friends to secure the liberty of slaves who had escaped into New York.

Dr. Madden quotes the following:

“His effort is said to have been overwhelming. The novelty of his manner, the enthusiasm which he exhibited, his broad Irish accent, his pathos and violence of gesture, created a variety of sensations in the audience. His republican friends said that his fortune was made, and they were right.”

From the first he attached himself to the Republican party.

His profession soon brought him in from $10,000 to $15,000 a year.

On Irish affairs

That his opinions regarding Irish affairs remained unchanged, maybe gathered from an extract from a letter to a friend who in after years urged him to revisit Ireland:

“I am too proud, when vanquished, to assist by my presence in gracing the triumph of the victor; and with what feelings should I tread on Irish ground? As if I were walking over graves—and those the graves of my nearest relations and dearest friends. No; I can never wish to be in Ireland, except in such a way as none of my old friends connected with the Government could wish to see me placed in. As to my children, I hope they will love liberty too much ever to fix a voluntary residence in an enslaved country.”

Death of Thomas Addis Emmet

On Wednesday, the 14th November 1827 he was seized with an apoplectic fit in the United States Circuit Court of New York, and on being conveyed home, expired in the course of the night.

The different courts were adjourned, and he was interred with every mark of public respect in St. Mark’s Church, Broadway, New York, where a monolith, with inscriptions in English, Latin, and Irish, marks his resting place.

Appearance and personality of Thomas Addis Emmet

Thomas A. Emmet was six feet tall, and stooped somewhat; his face wore a sedate, calm look; he was near-sighted, and used an eye-glass frequently.

Pleasant and playful in his family circle, abroad he was courteous and polished, dignified and self-respecting, without anything approaching to arrogance or self-sufficiency.

Family

His widow survived him nineteen years, and died in New York, at the house of her son-in-law, Mr. Graves, on 10th November 1846, aged 71.

Particulars of the other members of the Emmet family will be found in Madden’s Lives of the United Irishmen, also in Notes and Queries, 3rd Series.

Sources

331. United Irishmen, their Lives and Times: Robert R. Madden, M.D. 4 vols. London, 1858–’60.