NATIONAL EMBLEMS

By Terence O'Toole

[From the Dublin Penny Journal, Vol. 1, No. 2, July 7, 1832]

NATIONAL EMBLEMS. |

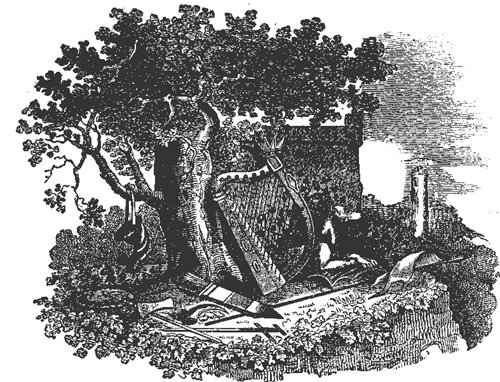

What will our readers think of us, when we are so very soft-natured as to tell them, that the wood-cut which graces the head of our page, was not done expressly for this number? The simple truth is, that, not anticipating the unprecedented demand which exists for our first number, we did our countrymen the injustice of supposing that our sale would be but a few thousands, a circulation which would scarcely afford even an occasional good wood-cut. We have now made arrangements with Mr. Clayton for a weekly series of views of remarkable objects and places in Ireland; commencing next week with "dublin, from the phoenix park." In our dilemma, we showed the one above to a very talented, tried, and worthy friend, a true Irishman, when he immediately exclaimed, "Oh this is capital! I will give you both a motto and a motive for it;" and shortly after he went away, the following letter was handed to us:

TO THE EDITOR OF THE DUBLIN PENNY JOURNAL.

SIR-Your wood-cut is, to my apprehension, as full of meaning to an Irishman, as any emblematic device I have seen. It represents peculiar marks or tokens of Ireland, which are dear to my soul. I am bold to say, the Round Tower, and the Wolf Dog, belong exclusively to our country; not so I allow the Oak, or the Shamrock, or the Harp; and, we may add, the Crown. But Irish oaks and Shamrocks, and Harps, as well as Irish Dogs, are known all the world over; and small blame to me if I try to say a little about them!

The Round Tower, to the right, is a prodigious puzzler to antiquarians. Quires of paper as tall as a tower, have been covered with as much ink as might form a Liffey, in accounting for their origin and use. They have been assigned to the obscene rites of Paganism - to the mystic arcana of Druidism - said to be temples of the fire worshippers - standings of the pillar worshippers - Christian belfries - military towers of the Danish invaders - defensive retreats for the native clergy, from the sudden inroads of the ruthless Norman. But all these clever and recondite conjectures are shortly, as I understand, to be completely overthrown, and the real nature of these Round Towers clearly explained, for the first time, in a Prize Essay, presented to the royal irish academy, by an accomplished antiquarian of our city. Sixty-five of these extraordinary constructions have been discovered and described in our island; of these, the highest and most perfect are at Dromiskin, Fertagh, Kilmacduagh, Kildare, and Kells.- There are generally the marks of five or six stories in each tower; the doors are from thirteen to twenty feet from the ground, and so low, that none can enter without stooping. The one nearest to Dublin, is at Clondalkin, four miles from town-though formerly there was one in a court off Ship-street. The most interesting one, both to the antiquarian and the lover of mountain scenery, is the one at the Seven Churches of Glendalough, within a day's drive of Dublin,- the scene of the legend given in your first number, and which if any one of your readers has not seen, he will not do himself justice, unless during the fine weather, he contrive to pay it a visit.

The next of our national peculiarities is that Wolf Dog, which, with paws most contemplatively crossed, is looking abroad, and as it were scouting with his keen round eye, for the game that, alas poor Luath! is no longer to be found on hill or curragh. Ireland, though it does indeed contain many a ravenous greedy creature, is yet no longer infested with wolves. Formerly it was not so. So late as the year 1662, Sir John Ponsonby had to bring into parliament a bill to encourage the killing of wolves. Their coverts were the bogs, the mountains, and those shrubby tracts, then so abundant in the island, and which remained after the ancient woods were cut down; affording shelter, not only for the wolf, but the rapparee. The last wolf seen in Ireland was killed in Kerry in 1710. But if our country was thus once famous for wolves, she was equally noted for its peculiar enemy,- and the Irish Wolf Dog, uniting all the speed of the greyhound with the strength of the mastiff, and depending on its eye, its foot, and its wind, would hunt down the game, which the canis veltris, or scent hound, had started for it. These Irish dogs were exhibited in the fourth century, at the Circensian games at Rome; they were an article of export from our isle in the middle ages; they are mentioned in the Welsh laws of Howel Dha, as belonging exclusively to the Cambrian princes and nobility; and a great fine is noted, as to be imposed on those who should injure them. They were employed to hunt the red deer, and the platyceros, or moose deer, as well as the wolf;- but the employment being gone, the breed, though not extinct, has ceased to be common; it is rarely to be seen, though I have marked a certain, grave, solemn gentleman, parading through town with a couple of these grim creatures stalking after him, while both he and his dogs looked as if they belonged to an age long gone by.

Now, the hound is couchant beside a goodly plant of trefoil. The draughtsman seemed determined that the Shamrock should be as gigantic as the dog. And why should not our favorite plant have a goodly appearance? Other Countries may boast of their trefoil as well as we; but no where on the broad earth, on continent or in isle, is there such an abundance of this succulent material for making fat mutton. In winter as well as in summer, it is found to spread its green carpet over our limestone hills, drawing its verdure from the mists that sweep from the Atlantic. The seed of it is every where. Cast lime or limestone gravel on the top of a mountain, or on the centre of a bog, and up starts the shamrock. St. Patrick, when he drove all living things that had venom (save man) from the top of Croagh Patrick, had his foot planted on a Shamrock; and if the readers of your Journal will go on a pilgrimage to that most beautiful of Irish hills, they will see the Shamrock still flourishing there, and expanding its fragrant honeysuckles to the western wind. I confess I have no patience with that impudent Englishman, who wants to make us believe that our darling plant, associated as it is with our religious and convivial partialities, was not the favourite of St. Patrick, and who would substitute in the place of that badge of our faith and our nationality, a little sour puny plant of wood sorrell! This is actually attempted to he done by that stiff, sturdy Saxon, Mister Bicheno: though Keogh, Threlkeld, and other Irish botanists assert, that the Scamar oge, or Shamrog, is indeed the trefolium ripens; and Threlkeld expressly says, that "the trefoil is worn by the people in their hats upon the 17th of March, which is called saint patrick's day, it being the current tradition, that by this three-leaved Grass, he emblematically set forth the Holy Trinity. However that be, when they wet their Scamar oge, they often commit excess in liquor, which is not a right keeping a day to the Lord!" The proof the Englishman adduces is the testimony of one Spencer, another Saxon, who, in his view of Ireland, describes the people, in a great famine, as creeping forth and flocking to a plot of Shamrocks, or water-cresses, to feed on them for the time; and he also quotes an English satirist, one Wytthe, who scoffingly says of those

" Who, for their clothing, in mantle goe,

" And feed on Shamroots, as the Irish doe."

But we are not so easily led, Mr. Saxon; we, Irishmen, are not quite disposed to give up our favorite plant at your bidding. In time of famine, the Irish might have attempted to satisfy hunger with trefoil, as well as they did two years ago, when such a thing as sea-weed was eaten,- for hunger will break through a stone wall. But do not the Welsh put leeks into their bonnets on St. David's day, and now and then they may eat their leek, as Shakespeare has it, as a relish either for an affront or for other sort of food; and small blame to an Irishman, if, when he feels that queer sensation called hunger, he chews a plant of clover! I, for one, when going into good company, would rather have my breath redolent of the honeysuckle plant, than spiced with the haut gout of garlic! Yet no Welshman would like to live upon leeks, no more than a poor Irishman would upon grass or trefoil; for there is, doubtless, as little nourishment for man in the one as the other. But to do Mr. Bicheno justice, he has another argument in favour of the wood sorrell being the favourite plant of our country, which is far more to an Irishman's mind. He says that wood-sorrell, when steeped in punch, makes a better substitute for lemon than trefoil. This has something very specious in it.

If any thing would do, this would. But let the Saxon do his best. Even on his own ground-even in London-he would find it very hard to convince our countrymen, settled in St. Gile's, that the oxalis acetosella, the sour, puny, crabbed wood-sorrell, is the proper emblem for Ireland. No; "the Shamrock-the green Shamrock," for me!

But what will I say about the Harp, the gnarled Oak, the regal Crown, the weapons of war, and of chase, that are strewed around? If any of your readers want to see a perfect specimen of an Irish harp, let them go to Trinity College Museum, and they will see there the genuine harp of Brian Boro, monarch of Ireland, who used to solace his proud and lofty spirit with this identical instrument, before he fell in his country's cause at the battle of Clontarf. To be sure it is not such a finished article as Mr. Egan of Dawson-street can supply, at the very goodly sum of a hundred and fifty guineas, and whose pedals are as complicated as the levers and articulations of the human foot. The old Irish harp was intended more for the poet than the musician, and was used as a subordinate accompaniment to the recitative of the minstrel; and who, on looking at the harp of Brian Boro, rude though it he, would not kindle into a rapture of enthusiasm, at the thought of that valiant minstrel king,- and feel his spirit swelling within him, as the words rise to his recollection-

" His father's sword he hath girded on,

" And his wild harp slung behind him!"

Yes! though the harp be hung on Tara's walls, though it he as mute as if the soul of music had fled, there was a time when the bard made its wild notes ring to his Tyrtean strains, and roused the warrior to the strife, or awakened within him the softer emotions of love and pity!

And who has not heard of Irish Oak? For though our hills and plains are now so bare of trees that they excite the admiration of all timber-hating Yankees, as they sail along our improved shores, yet formerly it was not so. No! It is said that Westminster Hall is roofed with oak, brought from the wood of Shillelagh: and a great many of our common names are significant of oak woods. As Kildare, the wood of oak; Londonderry, the oak wood planted by Londoners; Ballinderry, the town in the oak wood. At the bottom of all our bogs, and on the tops of our highest hills, roots of oak of immense size, are found; and we may fairly conclude, that though Ireland is now a denuded country, it was once the most umbrageous of the British isles. The customs of our country show that our people once dwelt under the green-wood tree; for an Irishman cannot walk or wander, sport or fight, buy or sell, comfortably, without an oak stick in his fist. If he travels, he will beg, borrow, or steal, a shillelagh; if he goes to play, he hurls with a crooked oak stick; if he goes to a fair, it is delightful to hear the sound of his cloghel-peen on the cattle's horns; if he fights, as fight he must, at market or at fair, the cudgel is brandished on high; and, as Fin Ma Coul of old, smiled grimly in the joy of battle, so his descendents shout lustily in the joy of cudgels -" Bello gaudentes-praelio ridentes!"

" In ruxion delighting,

" Laughing-while fighting!

" Leather away with your oak sticks !" is still the privilege, the glory, and the practice of Irishmen. Nay, more, while living, their meal, their meat, and their valuables, (if they have any-of course,) are kept in oak chests, and when dying, Paddy dies quietly, if assured that he shall have a decent "berrin," be buried in an oaken coffin, and attended to the grave by a powerful faction, well provided with oak saplings!

But, Mr. Penny Editor, I am taking up too much of your room. Another time, (if this pleases you,) I will give you something about the kingly crown, the dress, the armour, and the weapons of warfare, and of chase, which adorn your woodcut; for dearly do I love every thing connected with Ireland, and as I happen to have some little knowledge of the "ould ancient times," I may be inclined to write to you again. In the mean time, thou unmercenary patriot, I bid you farewell, leaving you my best wishes for the success of your Journal: for while others are striving to carry off our pounds, you merely want to pick up our pennies; and as reasonable people should get reasonable treatment, you may at any time bid "a penny for the thoughts" of

Yours to command,

TERENCE O'TOOLE