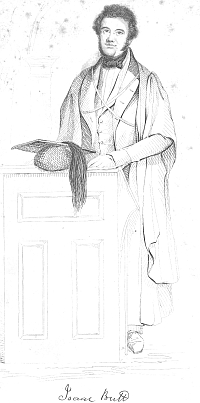

Isaac Butt, Esq. LL.D.

Professor of Political Economy in the University of Dublin.

From The Dublin University Magazine, Volume 16, Number 95, November 1840

THE boldest of our adversaries will not deny our magazine the credit of being genuinely and distinctively Irish. Ireland in the Past has been the subject of another series in our pages; Ireland in the Present is the chief subject of this. In the very remarkable person whose "counterfeit presentment" occupies the opposite page, we are much mistaken if we do not advance into the region of Ireland in the Future.

In one of the loveliest of his many lovely passages, Wordsworth has depicted the peculiar feelings with which the memory lingers on the image of the dead. The seal is then alone finally set; not till then can our impression of the object fix in absolute repose; for not till then can it never be lessened or contradicted by subsequent changes, faults, or failures. This is true indeed; yet it would be a poor thing were we universally compelled to adjourn the fulness of our feelings to such a period. If our own illustrious dead--our Burkes and our Berkeleys--have this peculiar stamp set upon their unchangeable glory; there is a charm, the very opposite indeed, yet scarcely less elevating, in the anticipations that gather round the opening stages of a career which men already feel to brighten with indications of a higher destiny to come. Shadows of uncertainty, of purposes interrupted, of possible change--must indeed cloud the view; and these cannot affect the calm and settled fame of departed greatness;--yet even these, perhaps, add in another way to the interest of the subject; they enliven, animate, diversify, our speculations as to its ultimate fortunes; and Hope becomes only the more truly and dearly Hope, when, even in its highest vividness, we are not permitted to exchange it for Certainty.

Those who have observed the short but brilliant and distinguished

preliminary career of the gentleman with whom we are now to engage our

readers, will not pronounce this language exaggerated. At a period when

the country "with strong crying and tears," demands the services of her

few devoted sons, a period of unexampled interest, difficulty, and

danger, we certainly should find it hard to name any who has answered

the call with equal promptitude, courage, and effect. Singularly

endowed for the busy work of public affairs,--natus rebus agendis--Mr.

Butt has but passed the threshold of active life to reach the position

ordinarily appropriated to long and laborious exertion. It is not the

energy of youthful enthusiasm that can do this; it is not the mere

talent of the gifted rhetorician; it is not even the country's faith in

the high and resolute principle of a leader;--though these (especially

the last) are all of them powerful and justifiable sources of

influence. We must seek the cause of Mr. Butt's strength in another

qualification as necessary as all these, though rarely, indeed, found,

as here, in combination with them; in the gift of sound common sense

and keen practical sagacity. A man may stimulate

his fellows to good by

the rest; he is not fit to guide

them without this; he may be the steam

to urge the machinery, but he cannot be the "governor" to temper and

direct its activity. To manifest this endowment so early in his

political course, is perhaps the very highest of Mr. Butt's claims upon

the respect and attention of his countrymen. It is no presumptuous

anticipation to expect much from the future energies of a mind that

begins with an attainment which numbers of eminent and gifted men pass

through life without ever reaching.

Those who have observed the short but brilliant and distinguished

preliminary career of the gentleman with whom we are now to engage our

readers, will not pronounce this language exaggerated. At a period when

the country "with strong crying and tears," demands the services of her

few devoted sons, a period of unexampled interest, difficulty, and

danger, we certainly should find it hard to name any who has answered

the call with equal promptitude, courage, and effect. Singularly

endowed for the busy work of public affairs,--natus rebus agendis--Mr.

Butt has but passed the threshold of active life to reach the position

ordinarily appropriated to long and laborious exertion. It is not the

energy of youthful enthusiasm that can do this; it is not the mere

talent of the gifted rhetorician; it is not even the country's faith in

the high and resolute principle of a leader;--though these (especially

the last) are all of them powerful and justifiable sources of

influence. We must seek the cause of Mr. Butt's strength in another

qualification as necessary as all these, though rarely, indeed, found,

as here, in combination with them; in the gift of sound common sense

and keen practical sagacity. A man may stimulate

his fellows to good by

the rest; he is not fit to guide

them without this; he may be the steam

to urge the machinery, but he cannot be the "governor" to temper and

direct its activity. To manifest this endowment so early in his

political course, is perhaps the very highest of Mr. Butt's claims upon

the respect and attention of his countrymen. It is no presumptuous

anticipation to expect much from the future energies of a mind that

begins with an attainment which numbers of eminent and gifted men pass

through life without ever reaching.

Of course we are not going to detail Mr. Butt's sayings and doings with the minuteness of regular biography. The pages of our Magazine, which have often been ornamented by his contributions, have also, in the fulfilment of their appointed task of political comment, reflected much of his public career as it passed before them. And to these we might refer, as forming themselves into a kind of consecutive annals; for periodical criticisms carry their own dates.

The lovers of facts and statistics, however, will scarcely pardon us if we do not satisfy their everlasting When? and Where? by informing them that the learned Professor of Political Economy first saw the light in the year 1813, in the County of Donegal; that his father was a very worthy beneficed clergyman in that land of moor and mountain; that he was in due time indoctrinated in Latin Grammar and the usual cyclopaedia of school literature at the Royal School of Raphoe; and that his entrance at the University with which he is still officially connected, took place in November, 1828. Mr. Butt's college career was highly distinguished; and the equal clearness and delicacy of his powers was manifested in a host of academic honours in the two great departments of scientific and classical attainment. The peculiar promptitude of his faculties (perhaps their most striking characteristic) seemed to promise certainty in securing the ultimate object of collegiate ambition--a Fellowship, in the examination for which that quality is especially required; and we believe that Mr. Butt, like most successful competitors in the undergraduate course, entertained at one period some intention of devoting himself to the pursuit. We are inclined to rejoice that a purpose was soon resigned which would have tended to limit by peculiar professional restrictions that free course of public usefulness of which we trust we have as yet seen only the commencement. In 1836, Mr. Butt became, after a close and interesting examination of several candidates, the Whately Professor of Political Economy; an office which, in spite of many other urgent engagements, he has not suffered to lose any of the reputation attached to it by his able and clear-headed predecessor in the Chair.

It was at an early period in the history of his mind and opinions, that those views were formed which have since governed the political career of Professor Butt. Before he had been long a resident in the University, and as soon as, in that little world of young and ardent minds, he could measure himself with his fellows, the great Question of the Day met him, and it found him what we find him still. With him to feel was to speak. At those Societies which are usually organised among students for the cultivation of the powers of thought and discussion, Mr. Butt was soon conspicuous for the free and fearless expression of opinion, and had already manifested (as we remember) many of the qualities that give him, at this day, so much influence over an assembly. The variety of his powers was exhibited (we must really be permitted to cashier our modesty for a sentence or two) in our own Magazine, with which he was long and intimately connected, and to which he contributed, along with numbers of political essays which attracted and influenced the general mind, many productions of imagination which the public will not readily forget. This is a subject of which we confess we are scarcely the fitting recorders; but we may mention to those who have not "plucked out the heart of our mystery," that for the touching and beautiful "Chapters of College Romance," they are indebted to the defender of the Irish Corporations.

But these were only the playful prolusions of a career destined for higher and more permanent objects. Mr. Butt, as all readers of our later political annals are aware, soon became an influential member of the successive associations formed in Dublin for the security of our perilled Protestantism. His ready and rapid elocution, his easy mastery of details, his bold and practical sagacity, at once made him a guiding spirit in these bodies; many of whose best and happiest efforts were the result of his advice and encouragement. If he could not say with Grattan that he had "rocked the cradle" of Irish Protestantism, he could at least declare with truth that he had cherished and directed its after years; God grant that, in the establishment of the measure to resist which his last and greatest efforts have been vainly devoted, he may not yet have to say that he has all but "followed its hearse!"

This is not the place to enter into details of the measures to which Mr. Butt consecrated his exertions during the momentous years that have followed the intrusion of Romanism into the British Legislature. It is not necessary. His principles were simple, however diversified in their exhibition. We have no authority to state them; and we know not whether our precis would meet his views in their full extent. We do not think, however, that we are very far astray, if we venture to sum them thus.

He believed, then, that, in the Romish party in Ireland, as represented and governed by its priesthood, there exists an unsleeping antipathy to Protestantism as a Religion and as a Government, as something to be hated and as something to be feared. He believed that this antipathy has never yet failed of practical realization, except from exhaustion, or from dread, or from despair. He believed that in this ineradicable enmity, is more or less included everything that is English, both because it is Protestant and because it is ascendant; because it is alike odious for its religion, and envied for its supremacy. Against this fearful hostility, thus twofold in its object, he held that our forefathers had fixed and fortified two citadels, each commanding and awing its respective foe. These are--these were--the Church and the Corporations; the Protestant Church to fortify the religious, the Protestant Corporations to guard the civil ascendancy; the one to represent British truth, the other to represent British power. These, and these almost alone, have moored us to the British anchorage; and with the surrender of these the British connection inevitably ceases to be practicable. These institutions thus hold a totally distinct office in Ireland from what they hold in England or in Scotland; nor, therefore, can any argument be drawn from changes in the latter to changes in the former portion of the empire. In England and Scotland they are (politically considered) ordinary institutions for ordinary purposes; in Ireland they are, besides this, the solitary fortresses of a threatened and detested authority. To sacrifice either to the other is miserably to mistake the object of both. It is yet more,--it is to weaken the very institution for whose security the sacrifice is made. To give up the Corporations for the Church is to desert the Church; as really (though not, of course, in the same degree) as to disestablish the Church in England would be temporally to abandon it;--it is to sacrifice the State that the Church of the State may prosper! And so surely as the one has fallen, so surely are its ruins to be erected into the rampart from which the enemy will storm the other. Short-sighted, inexcusably shortsighted is that policy which could promise the Romanising of Corporations to buy a few additional years of disturbed tranquillity for the Church; purchasing the postponement of hostility by subsidizing its forces and securing its eventual success!

Without entering more minutely into these questions of general policy on which Mr. Butt's opinions, we may presume, coincided with those of the conservative party at large, we rest upon this peculiar cause, as that which he has eminently made his own. To this sacrifice of the old bulwarks of British connexion, and this reconstruction of their materials into strongholds for the very disloyalty they were meant to control, Mr. Butt from the first steadily opposed himself. With an energy--and, we may add, with an ability--never surpassed, he denounced the measure, notwithstanding the lofty authorities by which it was accredited. Even that Name which has ever stood highest in his estimation, and which (can we wonder at it?) was alone with many an argument absolute and irresistible for the propriety of this awful revolution, could not overbear his deliberate convictions. Few who heard it can forget the noble passage which referred to the great statesman in the Mansion-House speech of the 13th of February last.

"But we are told, my Lord, that the rejection of this bill will be injustice to our country, and injustice to our Roman Catholic fellow-countrymen! I resist this bill because it will be injurious to both! it will degrade, it will impoverish our country--this is my argument why it should not pass--it is an argument that cannot be answered by the cry of "justice to Ireland." The most grievous blow that has ever been inflicted on the prosperity as well as the Protestantism of Ireland, will be this bill. It will interfere with our commerce, blight our energies, and disturb all our efforts for real or solid improvement. Once more I disclaim any nobility to my Roman Catholic fellow-countrymen, however I may hate the system that perverts the noble energies of our people. I will support any measure calculated to do real good to any class of my fellow-countrymen. I deny that this bill will benefit any one of my Roman Catholic fellow-citizens, except the priesthood and the few factious men who will share in the public plunder it will create. I challenge any of its advocates to show me in what conceivable way it will benefit the country. Let me be shown how it will develope its resources, encourage its trade, or promote its manufactures. On the contrary, it will legalize and perpetuate agitation; it will give chartered existence to those feuds and dissensions which are the curse of the country, which interfere with its commerce, retard its advancement, and fling the blighting influence of political animosity over every effort of every Irishman to advance himself by his honest industry.

"I appeal to the memorable declaration of the Duke of Wellington, in his place in the House of Lords, that a similar measure in England had made their towns places where men of quiet and respectable habits were every day less willing to dwell: this was in England--quiet, peaceable and happy England! The illustrious Duke knows well the terrible elements of strife which exist in Irish society--how fearfully aggravated will be the evils, which, even in England, are found inseparable from corporations constructed on revolutionary principles. May I venture, with all feelings of respect, of veneration, for that illustrious man, to appeal to him--will he inflict those evils on the Protestants of Ireland? It is not yet too late. Once before, his mighty energies vindicated, on the blood-stained field, the liberties of Europe, and preserved the throne of England from the ascendancy of wild and reckless revolution. In the name of liberty, in the name of the Protestantism of England, I appeal to him to do what, perhaps, no other human power can effect. As he values the reformed faith--as he values the permanence of the British throne--let him interpose his mighty influence between his country and ruin; let him save us from a tyranny worse than any he trampled down upon the glorious plains of Waterloo; let him rescue his country--the country of his birth--from the tyranny of Rome; in his glorious and his honoured old age stand forward to protect the Protestantism of Britain; and when the fame of his victories shall grow dim by time, and the glories of the warrior be coldly remembered, affectionate generations of Irish freemen will bless his memory, and revere his name, as the statesman who had saved them from Popish ascendancy. [This allusion to the Duke of Wellington was received with the most immense enthusiasm, which could not be repressed for many minutes; when it had subsided Mr. Butt continued.] Would to God that the illustrious veteran to whom I have ventured to allude had been present at this scene--that he could have witnessed the enthusiasm which the mention of his name had drawn from thousands of honest hearts. He has seen the excitement of the embattled field--he has returned home flushed with the exultation of victory, achieved in the cause of the freedom of his country and of Europe; but nothing could more thrill the breast of that illustrious man than the unpurchased, the unpurchasable enthusiasm of honest hearts. In the name of the people that have thus enthusiastically received the mention of his name, I appeal to him to be their friend in this hour of their deadliest peril--to defeat this accursed bill, and thus consummate a life of glory, and more, far more than atone for every political error that throws the spot of its darkness upon the sun of his fame.

"I owe this meeting many apologies for trespassing so long upon its attention. I have not exhausted the subject; I fear I have exhausted your patience; and I feel I have nearly exhausted my own strength. I have been indeed but ill equal to the task of addressing you; but if I knew that it was the last public meeting at which I ever should be present--that I should return home never again to meet an assembly of my fellow-men,--if I were to feel that this day I should be summoned from this world--there would not be an act of my life to which I would look back with more unmingled satisfaction, than the recollection, that in every way, at every risk, and every hazard--with the loss of, perhaps some friends--with the loss of some influence--exposing my motives to be questioned, I can scarcely say misunderstood--incurring the hostility of some who had hitherto been, or professed to be, my friends, I have given this bill my determined and my fearless resistance. Those who have resisted this bill have been charged with dividing the conservative party, by differing from the leaders of this party. Let our vindication be--I will condescend to no other--the statement I have laid before you to-day. This is the bill which we have opposed--this is the bill to which we are determined to offer resistance to the last."

His well-known opinions, his manifest command of the subject, and his unquestioned abilities as an orator, at length determined the members of the Dublin Corporation to place Mr. Butt in the situation, altogether unprecedented for one so young in his profession, of their Advocate at the Bar of the House of Lords.

We need not enlarge upon the skill and power with which this honourable duty was executed. Mr. Butt's speech on Friday May 15th, will long be remembered in an assembly richer than any in the world in masters of legal and political rhetoric. The effect of this appeal was, beyond all doubt, signal; nor probably was there ever delivered a speech at the bar of parliament which impressed even predetermined members so powerfully. The withering exposure of the devices of the corporation commission was peculiarly successful; the justification of the criminated exclusiveness of the Dublin Corporation since 1793, from the history of the times, brought conviction to every candid listener, and the descriptions, repeated and forcible, of the inevitably perilous result of investing with unlimited power, a body whose choice should necessarily lie "between insignificance and mischief," arrested the attention (and very manifestly to the witnesses of this singular scene) of even the most determined and distinguished abettors of the bill. The unimpeachable judgment of the gifted editor of the "Standard" is thus expressed:--

"The House of Lords was last night occupied during the whole of its sitting, in hearing the argument of Mr. Professor Butt, against the Irish Municipal Bill. Perhaps no argument delivered at the bar of either House of Parliament ever produced so manifest and extraordinary an impression. The learned gentleman was loudly cheered in the progress of his address, and still more enthusiastically at its conclusion; a great number of peers hurrying to the bar to thank and to congratulate him upon his success in exposing the true character of the measure under consideration. The unusual animation of the Duke of Wellington, the proof of which will be seen in our extracts borrowed from the Times, was perhaps the highest compliment that could be paid to the Speaker in the House. It has never been our practice to withhold praise where praise is due, and we truly tender our tribute of admiration to the eloquent advocate of the city of Dublin. It needed, perhaps, the powers of a consummate orator to tear away the veil which has hitherto shrouded this fiightful measure; but the veil once removed, an extraordinary revulsion of feeling was a necessary consequence."--Standard, May 16.

Our readers know, too well, how these efforts were ultimately defeated. The Bill is irrevocably passed, for no popular concession was ever wholly revocable; the future will be the commentary on the speech of Mr. Butt.

Of our learned Processor's outward man the appended Icon will furnish sufficient conception. Of his powers as a thinker, a politician, an orator, the public are able to judge from specimens still more unerring Of the two classes into which the respective styles of the Greek and the Roman orator seem to have divided all our estimates of eloquence, there can be no doubt of the allocation of Mr. Butt. He is beyond question Demosthenic. The characteristics of his manner are vigour, decision, and argumentative cogency. He illustrates only to illustrate; and never loses the substance in the accidents, or forgets the goal in the way that leads to it. No speaker so young in the art ever talked less for talking sake. From one so richly gifted, his Country, which is already his debtor, has a right to expect things yet more and mightier to come.

Mr. Butt was called to the Bar in 1838.