The O’Brien Family

(Crest No. 1. Plate 1.)

THE O’Brien family is descended from Milesius, King of Spain, through the line of Heber, third son of that monarch. The founders of the family were Brian Boroimhe, or Boru, King of Ireland, A. D. 1002-1014, and Moriertach O’Brien, last King of Ireland, of the race of Brian Boru, A. D. 1089.

Through their descent from Cormac Cas, son of Olliol Ollum, King of Munster, A. D. 177, and his consort, Sabia, daughter of Con Kead Caha, or Con of the Hundred Battles, King of Ireland, A. D. 148, the blood of both Heber and Heremon is united in this family.

The ancient name was Brian, and signifies “The Author.” The titles of the chiefs of the sept were Prince of Thomond, and King of Cashel and Munster, and their possessions were located in the present Counties of Cork, Limerick and Clare, then known as “O’Brien’s Country.” This territory had been in the possession of the O’Brien sept from the time of Heber, and most of the Kings of Munster were of the O’Brien branch. From this stem sprung all the nobility and gentry of Munster.

The chieftains and princes of the O’Briens were inaugurated at a spot called Magh-Adhair, now called Moyry Park, and situated in the townland of Toonagh, parish of Clooney, barony of Upper Bunratty, County of Clare, about three and a half miles west of Tulla. The mound on which the O’Briens were inaugurated is still to be seen at this place. It is of an irregular form, and measures 102 feet in length and 82 feet in breadth.

In the year 1002 Brian Boru, then King of Thomond and ruler of Munster, usurped the throne of Ireland, as has been truly said, by the right divine of being the fittest man to rule. He was the greatest of Irish monarchs, and were it not for his death at Clontarf, he would have consolidated the Irish monarchy, and rendered the nation proof against all designs and attacks on the part of Dane or Anglo-Norman. During his reign order prevailed, the wrangling and predatory chiefs were crushed, internal improvements were promoted, churches and schools sprung up again, and the arts of peace were cultivated.

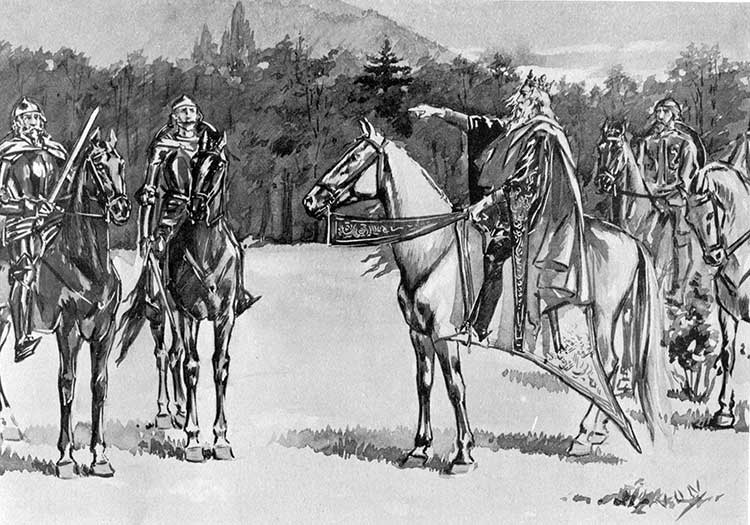

KING BRIAN,

Issuing his Orders on the Morning of the Battle of Clontarf.

Having defeated the Danes in more than a score of battles, and shattered their power, these ferocious adventurers, who had imposed their sway on England and parts of the European Continent, prepared to make a supreme effort to overthrow King Brian and regain their lost conquests.

Many of the Irish chiefs and petty princes were chafing under Brian’s strong and orderly rule, and accordingly formed a league with the Northmen against the Irish monarch.

The Northmen secured all the reinforcements that could be raised in Denmark, the Orkneys and the Hebrides, which, with their forces in Ireland and the Irish of Leinster, aggregated twenty thousand men. To oppose these Brian had about an equal number, consisting of the forces of Munster and South Connaught, and some levies of the Eoganachts of Scotland.

The contest took place on Good Friday, A. D. 1014, and lasted from early morn to four o’clock in the afternoon. The Northmen and their allies were utterly defeated, having left over seven thousand of their number slain on the field.

The power of the Northmen was forever broken, and the part taken by Spain and Hungary, or the Crusaders, at a subsequent period in Asia, in defense of Christendom as against Mahomedism, was not more important or more heroic than that accomplished by Brian and his lieutenants against the equally dangerous Danish idolatry and Odinism in Western Europe.

Of those who fell on the Irish side on that memorable day were Brian himself, his oldest son, Murrough, and Tourlough, a son of Murrough, a youth of fifteen years of age, who, according to the Annals of Clonmacnoise, was “found drowned near the fishing weir of Clontarf, with both his hands fast bound in the hair of a Dane’s head, whom he had pursued to the sea, at the time of the flight of the Danes,” and finally Conaing, nephew to Brian.

This extraordinary occurrence of the death of the ruling monarch and the two heirs in the immediate line of succession on the same day, left the Irish throne vacant, or at the mercy of the most successful adventurer. The weak Malachy again resumed the throne, but only nominally ruled. Aimless wars and dissensions followed, with the usual disastrous results. The national unity that had been temporarily effected by Brian gave way to the loose régime of the past, and when the Anglo-Normans landed on the Irish shores in the following century they found, instead of a united nation and a strong central power, a distracted people and a set of warring princes and chiefs, each intent only on maintaining his own power, or adding to it at the expense of his neighbor.

King Brian Boru was the first to decree that the Irish should assume surnames, in order the better to preserve the genealogies of all the families of pure Milesian descent.

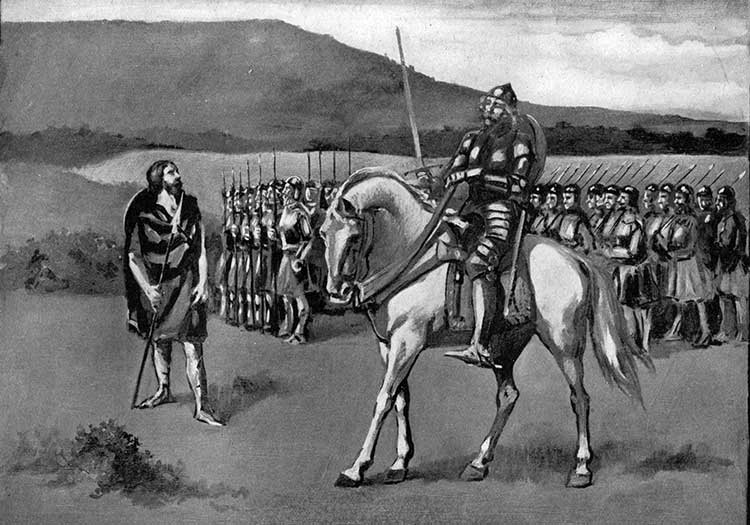

The O’Brien family has always filled a large space in the history of Ireland. They steadfastly resisted the English invaders, and Edward the First granted their territory to Thomas de Clare, son of the Earl of Gloucester. In the contest that ensued the chief of the O’Briens was slain, but his sons continued the war, and finally expelled the invaders. A few settlements of the foreigners were allowed to remain, but only on the condition of adopting the language and manners of the country. In 1565 Sir Henry Sidney, the Lord Deputy, changed the name of O’Brien’s Country to that of Clare, after its Anglo-Norman grantee.

Murrough O’Brien surrendered his kingdom to Henry the Eighth, who created him Earl of Thomond and baron of Inchiquin, but he and his descendants long continued to be the de facto rulers of the territory.

MURROUGH O’BRIEN

The O’Briens were loyal to the Stuarts, and after the defeat of King James the Second, whose cause they had warmly espoused, suffered severely.

Many of them rose to distinction in the armies of France and in the military service of other countries. Daniel O’Brien, third Viscount Clare, after having raised two regiments of foot and one of dragoons in the cause of King James the Second, and fought at the Boyne, retired to France with his regiments, which subsequently formed a part of the Irish Brigade. One of these regiments, commanded by his son, Charles O’Brien, specially distinguished itself at Ramillies in 1706, where, out of a total of eight hundred men, thirty-eight officers and three hundred and twenty-six soldiers fell. Both of Viscount Clare’s sons fell in battle, Daniel, the fourth Viscount, dying at Pignerol of wounds received at Marsaglia, and Major-General Charles, the fifth Viscount, at Ramillies.

Clare’s estates, consisting of sixty thousand acres, were seized by the Crown after his withdrawal to France. It was “granted” by King William the Third to Joost Van K. Keppel, one of his majesty’s Dutch favorites, who was also created Earl of Albemarle.

Viscount Charles O’Brien left one son, Charles, the sixth Viscount Clare, by his marriage with the daughter of the Hon. Henry Bulkley, Master of the Household to King Charles the Second of England. Although but a child at the time of his father’s death at Ramillies, King Louis the Fourteenth, desiring to continue the command of this regiment in the family, granted him the title of succession to the Colonelship, his kinsman, Lieutenant-Colonel, afterward Major-General, Murrough O’Brien, being meantime placed in actual command. The latter was one of the most distinguished officers of his day, having participated in nearly a dozen campaigns, and more than thirty battles and sieges. After his death Charles O’Brien, the sixth Viscount of Clare and ninth Earl of Thomond, succeeded to the actual command, August, 1720. He signalized himself in several campaigns, and was finally raised to the rank of Marshal of France, nominated Chevalier of the Orders of the King, and made the recipient of many other dignities. His name is intimately associated with the history of the Irish Brigade in France by the fact that he was in command of that body of troops at the battle of Fontenoy.

This famous victory was the Waterloo of the eighteenth century, with the difference that the French were the victors, and the British and their allies the vanquished. It was fought May 11, 1745, by the French and Irish under King Louis Fifteenth (though Marshal Saxe was the real commander), and the British and their Dutch and Hanoverian and Austrian allies, commanded by the Duke of Cumberland, son of King George the Second of England, and best known as the butcher who massacred the Scotch at Culloden. The forces of the allies numbered 55,000; the French 40,000, the latter having left 6,000 men to guard the Scheldt and 18,000 to continue the investment of Tournay, which was held by a garrison of 9,000 Dutch.

This historic battle has been so frequently and minutely described that we may pass it over in a few words. It lasted eight hours, during which time the English and their allies bravely and incessantly assaulted the French positions, and were as bravely repulsed. At length the Duke of Cumberland massed a solid column of English and Hanoverians, numbering between 15,000 and 16,000 men, flanked by twenty cannon, and proceeded to penetrate the French center at the only weak point in the line.

The French resisted desperately, and inflicted terrible loss on the advancing column, but went down before it, shattered and broken, infantry, cavalry and artillery. It penetrated the French position, and moved like a huge, resistless wedge toward the headquarters of King Louis, who had already prepared to fly, and would have fled, but that the French officers refused to act on his majesty’s orders.

It was at this critical juncture that Colonel Count Lally, who saved the retreat at Dettingen, and who this day commanded a regiment of the Irish Brigade, impressed on the Duc de Richelieu that the only means of saving the day was to batter the head of the advancing column with cannon, charge it in flank with the reserves, and attack it on all sides with the remaining forces simultaneously. The plan was instantly carried out.

The Irish Brigade had been held in reserve all day, and consisted of the regiments of Clare, Lally, Dillon, Berwick, Roth and Bulkeley, Fitz-James’ regiment of Irish horse having been detached to act with the French cavalry. They were made up of very young men in the highest state of discipline, fresh and burning to meet their English foes. They were supported by the two French regiments of Normandie and Vaisseany.

According to Voltaire, Lally made the following little speech before moving: “March against the enemies of France and of yourselves, without firing, until you have the points of your bayonets upon their bellies.”

The English advanced with grim, courageous front, loading and firing as if on parade, with musketry and cannon loaded with cartridge shot, in front and from both flanks, the officers even placing their swords on the gun barrels to make their men fire low. The French attacked them in front and on the left flank, while the six Irish regiments, with a shout heard above the din of more than a hundred thousand combatants: “Remember Limerick and English perfidy!” struck them on the left flank. “Soon,” says a writer of the day, in a letter from France, “as the English troops beheld the scarlet uniform and the well-known fair complexions of the Irish; soon as they saw the brigade advancing against them with fixed bayonets, and crying out to one another in English, ‘Steady, boys! Forward! Charge!’ too late they began to curse their cruelty which forced so brave a people from the bosom of their native country to seek their fortunes, like the wandering Jews, all over the world, and now brought them forward on the field of battle to wrest from them both victory and life!”

CHARGE OF THE IRISH BRIGADE AT FONTENOY.

The English wavered and reeled before the shock, but rallied and fought with stubborn valor, but quickly under the combined assault broke in confusion and ran pell-mell, tumbling over one another and of the dead that cumbered the ground. The entire affair lasted less than ten minutes, but those minutes were pregnant of momentous results. France was saved from disaster; Tournay, Ghent, Oudenarde, Bruges, Dendermond and Ostend fell immediately; the designs of England on the Continent were frustrated, and Holland was reduced from a first-class power to the status she occupies to-day. The brigade, however, suffered fearfully; one-fourth of its officers, including the gallant Colonel Dillon, and one-third of the rank and file being slain.

Thomas Davis describes this memorable event in the following vigorous lines. His reference to the “6,000 English veterans” is misleading, however, as, with the allies, the column numbered between 15,000 and 16,000, as above stated:

Thrice, at the huts of Fontenoy, the English column failed,

And twice, the lines of Saint Antoine, the Dutch in vain assailed;

For town and slope were filled with fort and flanking battery,

And well they swept the English ranks and Dutch auxiliary.

As vainly through De Barri’s wood the British soldiers burst,

The French artillery drove them back, diminished and dispersed.

The bloody Duke of Cumberland beheld with anxious eye,

And ordered up his last reserve, his latest chance to try;

On Fontenoy, on Fontenoy, how fast his generals ride!

And mustering come his chosen troops, like clouds at eventide.

Six thousand English veterans in stately column tread,

Their cannon blaze in front and flank, Lord Hay is at their head;

Steady they step adown the slope—steady they climb the hill;

Steady they load—steady they fire, moving right onward still,

Betwixt the wood and Fontenoy, as through a furnace blast,

Through rampart, trench, and palisade, and bullets showering fast;

And on the open plain above they rose, and kept their course,

With ready fire and grim resolve, that mocked at hostile force,

Past Fontenoy, past Fontenoy, while thinner grow their ranks—

They break, as broke the Zuyder Zee through Holland’s ocean banks.

More idly than the summer flies, French tirailleurs rush round;

As stubble to the lava tide, French squadrons strew the ground;

Bombshell, and grape, and round-shot tore, still on they marched and fired—

Fast from each volley, grenadier and voltigeur retired.

“Push on, my household cavalry!” King Louis madly cried;

To death they rush, but rude their shock—not unavenged they died.

On through the camp the column trod—King Louis turns his rein;

“Not yet, my liege,” Saxe interposed, “the Irish troops remain”;

And Fontenoy, famed Fontenoy, had been a Waterloo,

Were not these exiles ready then, fresh, vehement and true?

“Lord Clare,” he says, “you have your wish, there are your Saxon foes!”

The Marshal almost smiles to see, so furiously he goes!

How fierce the look these exiles wear, who’re wont to be so gay,

The treasured wrongs of fifty years are in their hearts to-day—

The treaty broken ere the ink wherewith ’twas writ could dry,

Their plundered homes, their ruined shrines, their women’s parting cry.

Their priesthood hunted down like wolves, their country overthrown—

Each looks as if revenge for all were staked on him alone.

On Fontenoy, on Fontenoy, nor ever yet elsewhere,

Rushed on to fight a nobler band than these proud exiles were.

O’Brien’s voice is hoarse with joy, as, halting, he commands,

“Fix bay’nets!” “Charge!”—like mountain storm, rush on these fiery bands!

Thin is the English column now, and faint their volleys grow,

Yet mustering all the strength they have, they make a gallant show.

They dress their ranks upon the hill to face that battle-wind—

Their bayonets the breakers’ foam, like rocks the men behind!

One volley crashes from their line, when, through the surging smoke,

With empty guns clutched in their hands the headlong Irish broke.

On Fontenoy, on Fontenoy, hark to that fierce huzza!

“Revenge! remember Limerick! dash down the Sacsanach!”

Like lions leaping at a fold, when mad with hunger’s pang,

Right up against the English line the Irish exiles sprang;

Bright was their steel, ’tis bloody now, their guns are filled with gore;

Through shattered ranks and severed files, and trampled flags they tore;

The English strove with desperate strength, paused, rallied, staggered, fled—

The green hillside is matted close with dying and with dead.

Across the plain, and far away passed on that hideous wrack,

While cavalier and fantassin dash in upon their track.

On Fontenoy, on Fontenoy, like eagles in the sun,

With bloody plumes the Irish stand—the field is fought and won!

Outside of the two ennobled branches of the O’Briens in the French service, there were five other officers of the name and collateral branches of the family, all Chevaliers of the Order of St. Louis.

Of the descendants of this family in America in Colonial days, the O’Briens of Maine were especially prominent. John O’Brien and his six sons fought the first naval battle, and won the first naval victory for the United States, a victory which Fennimore Cooper calls “The Lexington of the Seas.” The O’Brien brothers, with about sixty volunteers, most of whom had no better arms than pitchforks, took possession of a lumber sloop in the river, and by the aid of boats towing ahead and the use of sweeps brought up alongside the British armed schooner “Margaritta.” Under a fierce discharge from the enemy, the Americans boarded her, and after a spirited struggle captured her. The old lumber sloop was named the “Liberty” by the people of Machias; that was the first American battle-ship. It was only a few days after the battle of Lexington, and Cooper, comparing it to Lexington, pertinently says: “Like that celebrated conflict, it was a rising of the people against a regular force—was characterized by a long chase, a bloody struggle and a triumph. It was also the first blow struck on the water, after the war of the Revolution had actually commenced.”

The English, having fitted out two other armed schooners at Halifax, the “Diligence” and the “Tapnanquish,” to recapture the “Margaritta,” Captain O’Brien and Colonel Foster went out to meet them with the “Liberty” and the “Margaritta.” In less than five minutes after the encounter the two British vessels were captured. Three weeks later another expedition was fitted out, consisting of a frigate, a twenty-gun ship, a brig of sixteen guns, and several schooners, containing about 1,000 men. Captain Jeremiah O’Brien and Colonel Foster prepared to meet this formidable flotilla. O’Brien and Foster mustered a force of a hundred and fifty volunteers, who met the enemy about five hundred strong at Scott’s Point, a few miles below the town. As the British approached the American force, O’Brien addressed his men as follows: “You see the odds we have to contend with; if there is any man here who is sick of his bargain and wishes to leave, in heaven’s name let him be off.” Not a man moved. Colonel Foster said: “Captain, we can meet them; we have not a skulker in the ranks.” The Americans were drawn up in double rank—O’Brien having charge of the front and Foster of the rear division. The front rank was to deliver their fire, then fall back, give place to the rear rank, while the former reloaded, and repeat the maneuver, and if pressed too closely, meet the enemy with clubbed muskets.

When the English arrived within a hundred feet of the breastworks this order was carried out. After the second volley had been fired the Americans were still behind the breastworks, and the English were hurrying back toward the water. After another vain effort they gave up the attempt, placed their wounded on the brig and stood out for Halifax.

After many daring deeds, in which he severely punished the enemy, Captain O’Brien was taken a prisoner and detained in the prison guard ship, the “Jersey,” about six months, enduring the wretchedness which was the lot of the numerous American prisoners confined on board that vessel. He was afterward carried to Mill Prison, England, where he remained six months. Designing to attempt an escape, he purposely neglected his dress and whole personal appearance for a month. The afternoon before making his escape he shaved and dressed himself in decent clothes, so as to alter very much his personal appearance, and walked out with the other prisoners in the jail yard. Having secreted himself under a platform, and thus escaping the notice of the keepers, he was left out of the prison after it was shut for the night. He escaped from the yard by passing through the principal keeper’s house in the dusk of the evening. Although he made a little stop in the bar-room of the house he was not detected, being taken for a British soldier. In company with Captain Lyon and another American who had also escaped from prison, he crossed the Channel to France and returned to America.

After his arrival he was given command of a small but fast sailer named the “Hibernia,” carrying six three-pounders. With this little craft he captured the English man-of-war “General Pattison,” carrying sixty-one six and nine pounders, with six swivels, commanded by Captain Chiene. The same day he took another English vessel carrying twelve six pounders, and brought them into port. He died in 1818, aged seventy-eight years.

Among the modern representatives of the O’Briens, the name of William Smith O’Brien, of Forty-eight fame, is known and honored as a type of noble courage and unselfish patriotism. The name of O’Brien has ever been prominently connected with the hierarchy and clergy, both of Ireland and this Continent, and many of them have acquired high distinction in the Church for their learning and ability. Of the many eminent men of this name in the Church to-day, we may mention the

Most Rev. Cornelius O’Brien, Archbishop of Halifax, Nova Scotia, a man of distinguished ability as poet, orator and writer.

In the professional world this name is also prominent. In the legal profession we have that distinguished jurist, Judge Morgan J. O’Brien, of the Supreme Court of New York—a man whose judicial record and personal integrity have gained for him the esteem and confidence of the entire community. Of the many men of the name who have attained prominence in the business and financial world, may be mentioned William and John O’Brien, of Wall Street, New York; O’Brien, of San Francisco, of Bonanza fame; Commissioner Miles O’Brien, of New York City, and the O’Briens of Montreal, Canada.