Grania Uaile (Grace O'Malley): her children and the murder of her son

HER CHILDREN—MURDER OF HER SON

By this her first marriage with Donall an Chogaidh, Grania tells us she had two sons, Owen and Morogh. Her eldest son, Owen, was married to Catherine Burke, daughter of Edmund Burke of Castlebar, by whom she had a son, Donall O’Flaherty, still living when she wrote. This Owen, she said, was always a good and loyal subject, in the time of Sir Nicholas Malby, and also under Sir Richard Bingham, until the Burkes of McWilliam’s country and the Joyes began to rebel. Then Owen, for the better security of himself, his flocks and his herds, did, by direction of Sir Richard Bingham, withdraw into a strong island.

At the same time a strong force was sent under the lead of Capt. John Bingham (brother of Sir Richard) to pursue the rebels—the Joyes and others. But missing them, they came to the mainland—right against the said island—where her son was, calling for victuals, whereupon the said Owen came with a number of boats, and ferried all the soldiers over to the island, where they were entertained with the best cheer that could be provided.

That very night Owen was apprehended by his guests, and tied with a rope together with eighteen of his chief followers. In the morning the soldiers drew out of the island 4,000 cows, probably by ropes, 500 stud mares and horses, and 1,000 sheep, leaving the rest of the poor people on the island naked and destitute.

The soldiers then brought the prisoners and cattle to Ballynahinch, where John Bingham halted. The same evening he caused the eighteen prisoners to be hanged, amongst whom there was an old gentleman of four score and ten years, Theobald O’Toole by name.

The next night a false alarm was raised in the camp at midnight, when Owen O’Flaherty, who was lying fast bound in the tent of Captain Grene O’Molloy, a follower of Bingham’s, was murdered with twelve deadly wounds, and so, miserably ended his life. Her second son, she adds, Morogh O’Flaherty, is now living, and is married to Honora Burke of Derrymaclaghney, of the Maghera Reagh, Co. Galway.

This murder of Owen O’Flaherty, eldest son of Grania Uaile, is one of the ugliest deeds of Bingham’s black record in Connaught. It was not directly his own doing, but it was the doing of his brother and agent, Captain John Bingham. It was one of those utterly cruel and treacherous deeds which still tend to preserve bitter memories in the hearts of the western Gael.

Mr. Knox, in his paper on Grania in the Galway Archaeological Journal, thinks that this isle of tragedy was Omey. I am inclined to think it was rather Innisturk, near Omey, for Omey could at any time be reached dry-shod at low water, or even at half-tide, but Innisturk has always a deep narrow channel between its shore and the mainland. The English account describes this channel as a “gut” of the sea, which is accurate enough.

CLARE ISLAND

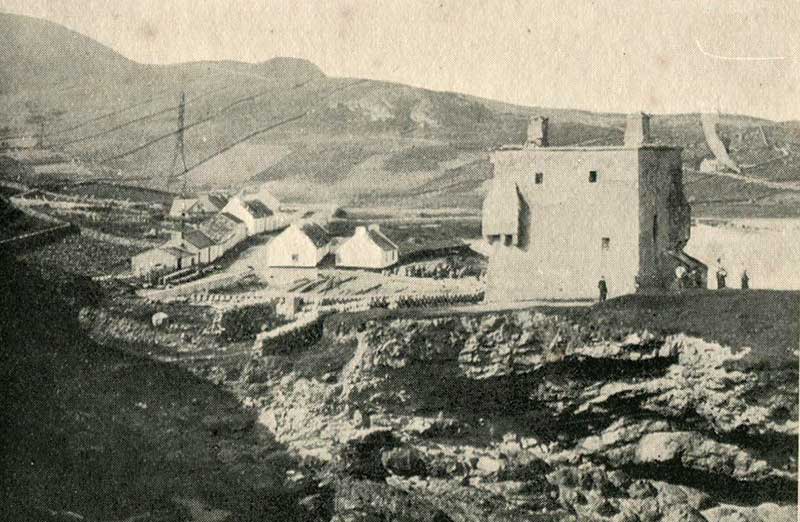

Clare Island Castle - west view

After the death of her husband, Donall O’Flaherty, Grania probably returned to Clare Island, where she felt most secure and most at home. Her sons were likely at fosterage, and it is probable she took her young daughter with her, for Bingham expressly tells us that the Devil’s Hook of Corraun, their near neighbour in Clare Island, was her son-in-law.

She doubtless made Clare Island her headquarters, and either built or strengthened the castle which still stands on a cliff over the little harbour. It was admirably situated close to the beach, on which her galleys were drawn up under her own eyes, so that when opportunity offered they were easily run down to the shore, and she would thus be ready to make her swoop on any part of the western coast without difficulty.

With the Devil’s Hook at Darby’s Point or Kildavnet, and her cousins or nephews at Murrisk, and she herself at Clare, Grania held a very strong position against all her foes. But she was not content with one or two strongholds; she had at least half a dozen.

At this time the Castle of Belclare was not in her hands. It belonged first to McLaughlin O’Malley, chief of the name, and then to Owen Thomas O’Malley, who dwelt there in 1593.

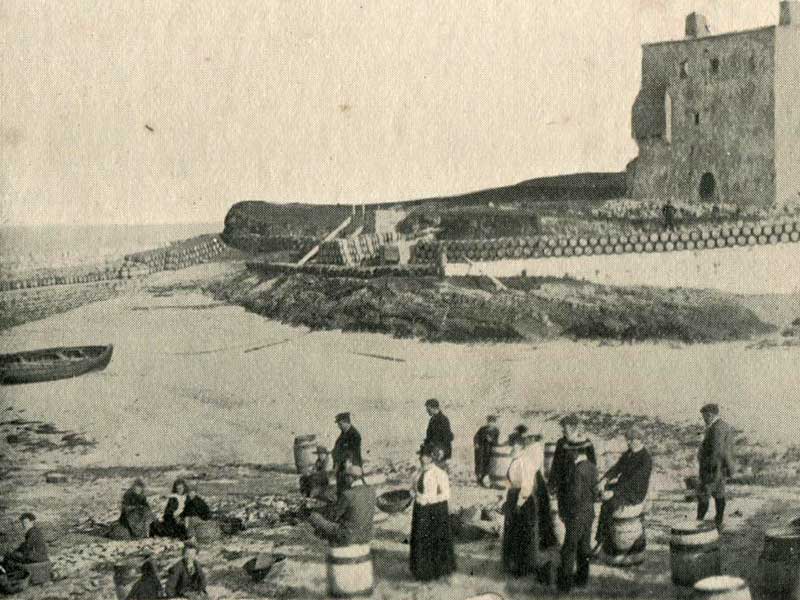

Clare Island Castle - east view

There is reason to think that Grania had also the Castle beyond Louisburgh at Carramore, of which only traces now exist. It would be a useful stronghold to secure her passage to and from Clare Island.

Then tradition connects her with the castle of Kildavnet, which she probably built to secure the passage through Achill Sound. It was thoroughly suited for that purpose, with deep water and secure anchorage against every wind and sea.

Moreover, she took care to ally herself closely with the lord on the other side. This was Richard Burke, whom the Dublin officials called the Devil’s Hook, which was an attempt at translating his Irish nick-name, Deamham an Chorain, the Demon of Corraun, because he was lord of that wild promonotory, and I daresay, always ready for any wild deed.

Grania gave her daughter in marriage to this Devil’s Hook, so between them they were well able to hold command of Achill Sound and Clew Bay. It is likely she gave him the ward of the Castle of Kildavnet. But she was not content with commanding the south entrance.

From her castle of Doona, which, it is said, she seized by stratagem, she held control of the whole of Blacksod Bay, for Doona was situated on the seashore of Ballycroy, close to the Ferry, looking out over the noble Bay, due west, to where the Blackrock light house now stands. Doona is now the mere remnant of a ruin, with its stones scattered amongst the sand hills by that desolate shore.

Kildavnet Castle

HER SECOND MARRIAGE

But Grania was not content with all these castles. She also got possession of Carrigahowley—more politely called Rockfleet—in this way.

It appears that it belonged to Richard Burke, as sub-tenant to the Earl of Ormond, commonly called Richard an Iarainn, or as the English writers call him Richard in Iron, because he always wore a coat of mail. His mother was an O’Flaherty, and so he was closely connected with the family of her late husband, and he resolved to marry the young and enterprising widow; nor was Grania unwilling, for so she would become mistress of Carrigahowely, which suited her well. She became, in fact, both master and mistress, for Sir Henry Sydney, the Deputy, tells us, that when he came to Galway in 1576, there came to visit him there “a most famous feminine Sea-Captain called Grania O’Malley, and she offered her services to me wherever I would command her, with three galleys and 200 fighting men, either in Ireland or in Scotland.

She brought with her her husband, for she was, as well by sea as by land, more than master’s mate to him. He was of the Nether Burkes, and now I hear is McWilliam Eighter, called by nickname Richard in Iron.”

The Deputy clearly saw that Grania was master both on land and sea, but he made a knight of Richard in Iron, which greatly pleased that worthy himself, and Grania also, for she was now Lady Burke, although we never heard of her being called by that name, either in history or fiction.

HER GALLEYS

This passage also shows that Grania had several large galleys, capable of carrying sixty or seventy men each, with twenty or thirty oarsmen to work them. At that time there were plenty of oak woods at Murrisk, which supplied material in abundance, and she doubtless had also skilled shipwrights to work it.

Then she had at Carrigahowley an excellent harbour, the best on Clew Bay—safe, deep, and well-sheltered; and Grania fully appreciated these advantages.

With such a fleet at her disposal, well manned, and well equipped too from the spoils of the sea, Grania was more than able to hold her own against all comers, even against the much larger English vessels which dare not follow her into the creeks and island channels of Clew Bay.

I am inclined to think that she and her seamen were not very scrupulous in differentiating their enemies; in fact she tells us herself, in reply to the Government interrogatories, that her former trade for many years was what she calls “maintenance by land and sea”; that is, she lifted and carried off whatever came handy on sea or shore from Celt or Saxon.

We know for certain that she raided Aranmore more than once, and even the great Earl of Desmond’s territory at the mouth of the Shannon.

TAKEN PRISONER

But there she came to grief, for having landed a party apparently near Tarbert on the Shannon, to raid the Earl’s country, she was taken prisoner by the Earl, who first put her in his own dungeon, and then handed her over to Drury, the President of Munster, by whom she was imprisoned, in all for nearly eighteen months.

She was then sent on to the Lord Deputy, who met her at Leighlin Bridge, from which he sent her on to Dublin, but when he came himself to Dublin he released Grania, for whom he felt some admiration, and allowed her to return once more to the West.

The Lord Deputy on this occasion describes her as governing a country of the O’Flahertys, which is probably a mistake for the O’Malleys, for Grania was certainly at that time the wife of Sir Richard Burke, but they lived mostly apart—he warring on the land, and she chiefly on the sea.