Grania Uaile (Grace O’Malley)

Lecture delivered in the Town Hall, Westport, on the 7th January, 1906.

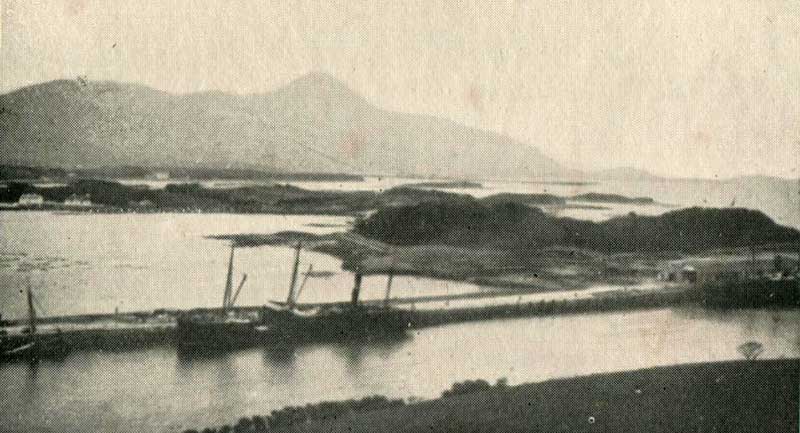

Clew Bay

EVERYTHING connected with Grania Uaile, the famous Queen of Clew Bay, ought to have a very special interest for the good people of Westport and its neighbourhood, for she is, so to speak, one of yourselves, and her memory ought to be for you a glorious inheritance, which you can fairly claim as your own. Her old castles around Clew Bay still plead haughtily, even in their ruins, for glories that are gone; the living traditions of her achievements still linger, like the mists on the slopes of Croaghpatrick, around your shores and islands, where she lived, and fought, and died.

She was, as I shall show, famous in her own time as the warrior Queen of Clew Bay; and she still continues to be by far the most famous Irish heroine known to our island story. To find her equal at all in Ireland we must go back to the far-distant past—to that famous Queen Meave of Rath Cruachain, who flourished about the beginning of the Christian era.

They were somewhat alike in war, diplomacy, and love, and both seemed to have ruled their husbands as well as their subjects. In her own times we can find no lady to compare with Grania except it be Queen Elizabeth of England, and although the Saxon Queen filled a higher place in a far wider sphere, I doubt very much if she were superior in any royal qualities to the warrior Queen of Clew Bay, and certainly, in some respects, she was much her inferior.

HER NAME

Her proper name in Irish, as you all know, was Grainne Ni Mhaille; Grania Uaile is the popular form; and Grace O'Malley is the polite English form, which, I daresay, the lady herself never heard.

It is strange we find no reference to Grania in what may be called our National Annals. Neither in the Annals of Lough Ce, nor in the Annals of the Four Masters, nor in the Annals of Clonmacnoise, do we find the slightest reference to Grania, because I daresay the official chroniclers would not recognise any female chieftain as head of her tribe.

It is to the State Papers we must go to get authentic information about Grania—that is to say, to the letters written to the Privy Council in Ireland or in England, by the statesmen of Queen Elizabeth who visited Connaught. Above all, we have one invaluable document, written in July, 1593, containing Grania's answers to eighteen questions put to her by the Government about herself and her doings, the authenticity of which cannot be questioned, and which gives us the most important facts in her personal history.

It is on these documents I base my narrative this evening. I cannot gather at present the floating traditions of Grania around Clew Bay, not because I undervalue them, but because I had not time to collect them, nor would I at present have time to narrate them.

HER PARENTS

“Her father was,” she tells us, “Dubhdaire O'Mailley, at one time chieftain of the country Upper Owle O'Mailley, now” (in 1593) she adds, “called the Barony of Murrisk. Her mother was Margaret Ni Mailley, of the same country and family.”

The O'Malleys had from immemorial ages been lords of the Owles, or Umhalls—that is, the country all round Clew Bay, now known as the baronies of Burrishoole and Murrisk.

It is said they derived their descent not from Brian the great ancestor of the Connaught kings, but from his brother, Orbsen; and hence they are set down in the Book of Rights as tributary kings to the provincial kings of Connaught. In the middle of the thirteenth century they were driven out of a good portion of the northern Owle by the Burkes and Butlers, but still retained down to the time of Grania some twenty townlands, or eighty quarters in Burrishoole, and held more of it as tenants to the Earl of Ormond.

The Burkes had also in Burrishoole some twenty townlands or eighty quarters, and the Earl of Ormond had ten quarters or forty townlands, which were usually set on lease either to the Burkes or to the O'Malleys. Grania also tells us that O'Malley's barony of Murrisk included all the ocean Islands from Clare to Inisboffin, making in all, with the mainland, twenty townlands, or eighty quarters of fairly arable land, not counting the bog and mountain.

BIRTH AND FOSTERAGE

We do not know when or where Grania was born, but as her father was at one time chief of his nation, it was most likely at Belclare, which was one of the chief castles of the family, and she was probably baptized at Murrisk. As Bingham describes Grania in 1593 as the “nurse of all rebellions in Connaught for the last forty years,” she must have been born about the year 1530, before Henry VIII. had yet changed his religion.

It is highly probable that Grania was fostered on Clare Island, which belonged to her family, and it was doubtless here she acquired that passionate love of the sea, as well as that skill and courage in seafaring, which made her at once the idol of her clansmen and the greatest captain in the western seas.

PERSONAL APPEARANCE

“Terra Marique Potens,” was the motto of her family, and Shane O'Dugan tells us that there never was an O'Malley who was not a sailor, but not one of them all could excel Grania in sailing a galley or ruling a crew. This open-air life on the sea, if it did not add to her beauty, gave her great strength and vigour. Sydney, the Lord Deputy, who met her in Galway in 1576, describes her, when she must have been about middle age, as “famous for her stoutness of courage, and person, and for sundry exploits done by her by sea.”

Whatever literary education she got in her youth she probably received from the Carmelite Friars on Clare Island, but I suspect, although she was afterwards married to two of the greatest chiefs in the West, that Grania knew more about rigging and sailing a galley that she did of drawing-room accomplishments. Sir S. Ferguson, in a fine poem, gives eloquent expression to her feelings while she dwelt on Clare Island, and sailed over the wide waters of the noble bay that spread around her, “where Clew her cincture gathers isle-gemmed”—

“Oh, no; 'twas not for sordid spoil

Of barque or seaboard borough

She ploughed, with unfatiguing toil,

The fluent, rolling furrow;

Delighting on the broad back'd deep,

To feel the quivering galley

Strain up the opposing hill, and sweep

Down the withdrawing valley.

“Or, sped before a driving blast,

By following seas up-lifted,

Catch, from the huge heaps heaving past

And from the spray they drifted,

And from the winds that tossed the crest,

Of each wide-shouldering giant,

The smack of freedom and the zest

Of rapturous life defiant.

“Sweet when crimson sunsets glow'd

As earth and sky grew grander,

Adown the grass'd unechoing road,

Atlanticward to wander,

Some kinsman's humbler heart to seek

Some sick bedside, it may be,

Or, onward reach, with footsteps meek,

The low, grey, lonely abbey.”

HER FIRST MARRIAGE

It is not unlikely that Grania was an heiress, and though she could never, according to the Brehon Law, become “the captain of her nation,” especially after marriage, she still seems to have always retained the enthusiastic love and obedience of her clansmen, especially in the islands. She must, of course, get a husband, and so they chose a fitting help-mate for a warrior Queen in the person of Donall an Chogaidh O'Flaherty, of Bunowan, in the barony of Ballynahinch. He was in the direct line descendant of Hugh Mor, and was acknowledged as the Tanist or heir-apparent to Donall Crone O'Flaherty, who claimed to be the chief of his nation, but Donall Crone had been set aside in 1569 by Queen Elizabeth, so that Donall the Fighter had no longer any claims as Tanist.

But when Donall of Bunowan, about the year 1550, sought and obtained the hand of Grania Uaile, he was the acknowledged heir to the headship of all the western O'Flahertys, and certainly after the death of Donall Crone ought to be the Chief Lord of all Connemara, although Teige na Buile contested his claims.

This alliance, therefore, united in the closest bonds of friendship the two ruling families of Murrisk and Ballynahinch, with nothing but the narrow estuary of Leenane Bay, or rather the Killery, between them. Moreover, it made the united tribes chief rulers of the western seas, so that when Grania sailed away from her island home, with the sea-horse of O'Malley and the lions of O'Flaherty floating proudly fore and aft from the mast-heads of her galleys, the young sea-queen must have been a happy bride, and expected happy days in her new home at Bunowan Castle.

BUNOWAN

Bunowan was at that time the chief castle of the O'Flahertys of Connemara. It was built near a small stream on the shore, and close to the old church of Ballindoon. There was an excellent harbour near at hand, sheltered from the west by the Hill of Doon, with deep water and good holding ground—just what Grania wanted. No doubt there were dangerous rocks and currents all round the entrance, but all these were well known to the natives, who could avoid them, but they were perilous to stranger craft, which would hardly venture to approach them, for there is no wilder coast all round the shores of Ireland, and there were then no lights either on Slyne Head or the Aran Islands. Hence, too, hostile galleys rarely ventured to approach that perilous rock-bound shore.

Regarding this marriage, Grania herself tells us in a business-like way that her first husband was called Donall “Ichoggy” O'Flaherty, and that during his life he was chieftain of the barony of Ballynahinch, containing twenty-four towns of four quarters of land to every town, paying the composition rent. After the death of her husband, Teige O'Flaherty, the eldest son of Sir Morogh O'Flaherty, entered into Ballynahinch, and ignoring the rights of the widow and her sons, “built therein a strong castle, and kept the same with the demesne lands of Ballynahinch for many years, until he was slain in the last rebellion of his father.” This was a hard hit at Sir Morogh na Doe, especially as the facts were undeniable.