Desmond

THE homes of the Geraldines of Desmond were scattered about the counties of Limerick and Cork and Waterford and the Highlands of Kerry; but in these there were three great independent cities, and the realms of Irish chiefs, O'Sullivans, MacCarthys, O'Donoghues, O'Mahonys, and others, who, though despoiled of much, clung to their places. It was only in Kildare that the Geraldines were wholly supreme. This was one of the reasons why that family lost Desmond for ever, but survived in Kildare. Even in that county their home, Carton, is a modern house, built without any consideration of danger. When once they had fallen, their adventurous days were finished. By their own river Avon Dhuff, the Black Water, stands a proud castle, Lismore, fit to be compared with the Butlers' hold at Kilkenny; but this, though it was protected by them for a time, is not linked with their name. Raleigh owned it, and from him it passed to the Boyles, and from them to the house of Cavendish, and now it is held by the Duke of Devonshire, and lords it over a trim little English town. The castles in which the Geraldines of Desmond rejoiced are ruins in ivy.

Sir Walter Raleigh profited by their calamity, much to the disgust of the Black Earl of Ormonde, and if you visit the forlorn town of Youghal, you will be apt to overlook their traces in seeking his home, Myrtle Grove. Yet that green gabled house is a building of yesterday compared with Saint Mary's Cathedral, built by them long ago. The house and the ruins stand close together, one inhabited still, and often sought for the sake of the legends that in its garden tobacco was first smoked in Ireland and the potato first planted, and the other neglected, and indeed shunned out of fear of ghosts. Raleigh was no friend to Ireland: it might even be argued that he was its worst enemy because he introduced the potato; but he is remembered while there is little thought of the race that loved it so well. Still, you cannot help thinking of them when you follow their sad and noble river. You could imagine that the depths of the Black Water were still haunted by the ghosts of the leaves that whispered above it when it ran dark below the forest of Desmond, for it is a wide river of shadows. Beyond doubt, it is haunted by the thought of the Geraldines: you will remember them at woody Dromana and calm Temple Michael and every turn of the shore. At Temple Michael was their burial-place. It is recorded that one of them was buried away from it, at Ardmore on the Waterford side, after fighting in vain, but could not repose there, and haunted the opposite bank at midnight for seven years, calling "Garoult arointha!" "Ferry Gerald over the river!" till some faithful clansmen of his brought his body across by stealth in the dark. This tale will remind you that the Black Water was a boundary river. Though the Geraldines soon acquired much of Waterford county, they did not rule there any more than did the Butlers in Wexford.

Torna the Druid prophesied (it is said) that a wind from the south-west would fell the great tree that covered all Ireland. This has been interpreted as a warning that the Fenians would land in the south-west and conquer. Whether they did or not, whether they ever landed at all or never existed, certain it is that the Danes and the Normans came up from the south-east like a devastating wind. That was Ireland's enticing and vulnerable shore: Agricola intended to bring his legions there, in the days when he marched up the Cornish coast and had dreams of expanding the Empire of Rome. So the south-eastern corner of Ireland—the counties of Wexford and Waterford—through attracting many invaders became foreign. The more daring adventurers marched inland; the wiser ones were content. For which reasons these counties became notably wise, and were at all times aloof.

The Danes founded Waterford City at the head of an inlet that had been called the Haven of the Sun till they came, and had been afterwards known as the Glen of Lamentation, because of the mourning that followed the many battles with them. They called their new citadel Vedr-fiord, because it was set beneath the point where the waters of the Suir and the Barrow united; and when three hundred years later the Normans arrived and gave them cause to lament in their turn, that name was preserved. Out of the five cities held by the Danes—Dublin, Cork, Limerick, Wexford, and Waterford—this was the one that kept their character most. "Intacta manet Waterfordia" was inscribed on its arms, and that motto was always justified. Cromwell besieged it in vain, and it would not admit the Royalist troops: it stood alone, not to be coerced or entangled in the wars of its neighbours. To this day it is a prosperous town, with wide and clean streets and an air of thrifty and sober independence.

It was not possible for the county to keep as intact as its capital did; yet like Wexford, it had a life of its own. Unlike Wexford, it was not thickly populated, and was long held by Norman houses; indeed even now its chief owners, the Beresfords, though they are derived from an ancestor who settled in Ulster when that province was planted by James I., represent the Le Poers. This county was fit for stately homes, being well-wooded and well-watered and fertile; even its mountains will repay cultivation, as was proved by the Trappist monks of Mount Melleray when they turned a bare hillside into rich fields. So the adventurers who found it first kept it as long as they could. For which reason, and because the peasants were as tough and intractable as their neighbours of Wexford, the masterful Geraldines failed on this side of their river. But they were at home in the pleasant county of Cork.

There is a solitary ivied tower standing by a small river, near Buttevant, in a deserted and bare glen. This is all that is left of their splendid fortress, Kilcolman. When they fell, it was granted to Spenser, with three thousand acres around it, on condition that he should reside in it and should allow no Irish to be on his lands. Here he wrote the Faerie Queene, not without thinking of them and of their knightly deeds in their haunted forest; and here he came under the spell of the glamour of Ireland. More than that, he came under the spell of Irish ill-luck; for the castle was burnt in the rising of 1598, and he was driven out of the country, broken-hearted. Nor were his descendants immune; William Spenser, his grandson, was evicted and transplanted to Connaught as one of the Irish Nation, thus incurring the doom which the poet had recommended as fit for all the barbarous Irish. Since which time the Spensers have vanished as utterly from ruined Kilcolman as have the Geraldines and the tall woods that once roofed the valley with leaves.

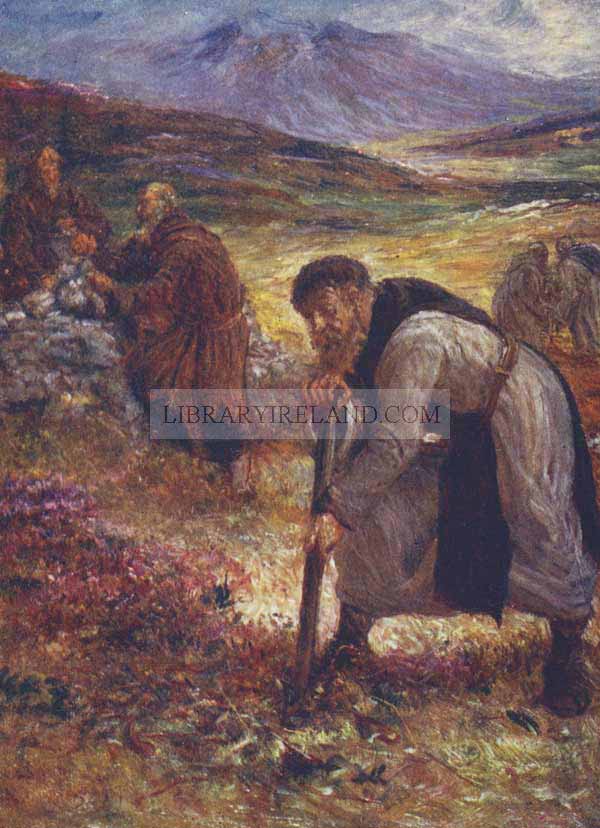

THE MONKS OF MOUNT MELLERAY

ARE of the Trappist order, one of great austerity. They rise every morning at 2 a.m., maintain perpetual silence, live entirely upon vegetable diet, and by their labour in the fields supply their own wants, and gain sufficient to entertain strangers hospitably.

Buttevant is said to have been named from a Norman war-cry "Push forward" "Boutez en avant"; and there are many other such traces of that people in these parts; but though they prevailed for a time, they could not eradicate the clans they subdued, for this was a country very dear to the Irish. It is probable that the people of Cork County had even then the character recognised now; for it is plain that they attracted their conquerors, and subdued them in turn, not by the sword, but with an irresistible kindness. Even Edmund Spenser, who, when he was not lost in gentle dreams, was evincing a peculiar ferocity which is remembered still by men who were never soothed by his verses, even he married one of their girls, and before and after his time many another foreigner came and saw and was conquered. So Cork, in spite of having enticed Danish and Norman and Spanish and French and English settlers, remained immutably Irish; and now though many of its inhabitants have dark foreign faces, and more have Cromwellian names, yet all of them speak with a tender brogue.

Here on every hand you find tenderness and brightness and "blarney." It is related that the word blarney was coined by Queen Bess. The Lord of Blarney Castle, a MacCarthy, so often beguiled her with amiable messages (it is said) that at length she exclaimed "that is all Blarney, and means nothing." Now, though the legend that she could talk Irish, having learnt it from her mother, Anne Boleyn, and discoursed in that tongue with Grace O'Malley, is probably false, still her descent from the Butlers entitled her to speak with authority; and it must be admitted that if she said this she was not far wrong. Cork blarney does not mean very much, beyond a pleasant desire to please: it is best explained by other words popular here, such as wheedling, deludthering, soothering. None of these denote any culpable guile. The people of Cork hold with Saint Augustine that an ounce of honey attracts more flies than a gallon of vinegar. Their light-heartedness does not seem to be Irish: you will find it nowhere else in this country, nor will you unearth any record that it ever was shown elsewhere in the past; it resembles the gaiety of France, and may be in part due to a French strain, but it seems natural here. The sunny and mild climate of the Land of many Waters (as an old Annalist called it) and the feminine loveliness of its undulating meadows accord with the nature ascribed to all who are born within sound of the Bells of Shandon.

THE RIVER LEE

The church spire in the distance is that of Shandon.

THE BELLS OF SHANDON

"With deep affection

And recollection

I often think of

Those Shandon bells.

Whose sounds so wild would,

In the days of childhood,

Fling round my cradle

Their magic spells—

On this I ponder,

Where'er I wander,

And thus grow fonder,

Sweet Cork, of thee;

With thy bells of Shandon

That sound so grand on

The pleasant waters

Of the River Lee."

—Rev. Francis Mahony.

The city earned its name "Rebel Cork" in the days when it supported Perkin Warbeck. It was independent and mercantile then, and always in arms against its "evil neighbours, the Irish outlaws"; but its long isolation ended when the ramparts were finally battered by Marlborough. If it is still Rebel Cork, that is due to the ultimate success of those neighbours, and to the fact that a warlike attitude pleases some of those Provencals of Ireland. It has no martial look, but rather a happy-go-lucky air of content. Yet if you turn into its by-ways, you will find misery and destitution. So, too, when you visit the Cove of Cork, that wide Haven of the Sun, you will be reminded of pleasure by the innocent sails of yachts. But it is also frequented by the emigrant ships. Alas, the emigrant ships! These have made it resemble that other Glen of Lamentation: its hilly shores have echoed the loud grief of a multitude. It would have been better for those exiles if they could have looked back for the last time on a scene less delightful; here they could not but feel how rich and kind a land they were leaving.

Limerick City, unlike Cork, has retained its martial appearance. There are great solid towers and sheer ramparts; but these are no longer defended, and are as obsolete as the vacant warehouses that tell of a forgotten prosperity. You feel that this is a place blighted in its prime by some strange misfortune; it is so silent and fallen that you could imagine it under a curse. Yet for a long time it ranked with Galway, it was as proud and as flourishing, and had a much older claim to respect, since it had been famous as a seat of the Danes. Like them, its people were always seafaring and mercantile and bellicose, till it was broken by its last siege in the days of William of Orange. After that time, it was gradually deserted; its men found their way to the foreign Brigades and later to America. Now, though that first impression is modified when you are familiar with the city, though you find that it has more commerce and life than you thought, these appear out of proportion, as when you see a small household live quietly in part of an ancient castle.

Limerick was influenced greatly by the Geraldines, for they were enthroned near it in Desmond Castle at Adare, on the shore of the lordly and impetuous Shannon. That was a royal house in a royal country: Kincora, the Palace at the Head of the Weir, once stood by the Shannon above it, and so did Castle Connell, the seat of the Kings of Thomond. Now Castle Connell is ruined, and of Kincora nothing is left save a grassy mound near Killaloe, and Desmond Castle is a green wreck among others, the remnants of monasteries that the Geraldines founded. Near all their great homes they built monasteries; it was their boast that they had been the chief patrons of the friars and monks, and in this, though they were but following the custom of Normandy, they agreed with the Irish one. This form of munificence was one of the things that made them congenial. You will not find that they were considered foreigners, as their rivals were always, and they were most Irish when they lived in the West, for they put off the trammels of alien life when they were here at Adare, or at further Castleisland above monastic Killarney.

Limerick County resembles Tipperary and Clare in its boldness; but its moors are more often cloven by valleys. Time was when it was sheltered by the Dark Wood, the forest in which the hunted Irish lay hidden during the fine months, only sallying out of it when the misery of the winter impelled them to a mad desperation,—they could not rest under the naked and moaning boughs. Now, though the forest was felled by the conquerors in Elizabeth's time, many of the hollows have grown woody again. And the men of this county have much in common with those of Clare and Tipperary, though they are of more mingled blood. The Germans who were brought to this island from the Palatinate, under Queen Anne, took a firmer hold here than anywhere else; and the descendants of the three thousand emigrants to whom lands in Limerick were given then are apart still and known as the Palatines. Besides these there were many Cromwellian settlers, for this was one of the parts kept by the soldiers. So the people have a robust and dogged strain; but their kinship with the natives of Cork has ensured a hilarity that is not to be found in Tipperary or Clare. Is it not celebrated in the old ballad "Garryowen na Gloria"?

When you go westward to the mountains you enter the oldest part of Old Ireland. The Highlands of Donegal are ancient enough, since there the folk seem to have altered so little since the days when Clan Connell flourished, and so is Connemara, though there the spirit that lingers still in the mountains belongs to a later time of misfortune; but Kerry appertains to a period of which nothing is known. In Killarney you will remember the monks; but that fortunate place is only an outlying nook of waters and trees and flowers. A dark river, fighting its way along a trough of the mountains on the brink of the Highlands, widens into pools above hollows and then into a small lake, and next into a larger one, and afterwards is constricted again till it reaches the ocean. Its two wide and sunlit expanses are now called the Lakes of Killarney. Because it reposes in them, they tell of rest amid toil and forgetfulness amid trouble. Their delicate light is the more welcome because it is contrasted with the gloom of the mountains. The nook has a restful and calm prettiness. This is such a place as a man would choose when abandoning a world he found too hard and seeking oblivion. So it was a favourite haunt of monks; but it does not suggest the grave silence of hermits as Glendalough does: it reminds you of the happiness found in scholarly cloisters and of peaceful and ordered lives. Though Innisfallen, the island where the Annals were written, is now a place of trees, and the cloisters of Muckross are left to the dead, the nook still is monastic. It is true that you will come on the hulk of a castle once held by the O'Donoghues of the Lakes, and will find pleasant spots vulgarised by such names as O'Sullivan's Punchbowl, and if you are foolish enough to allow the boatmen to plague you with stories, most of which have been made for English consumption, you will hear many absurd legends of impossible chiefs, and very little about the monks; but if you dwell on these things, you will fail to appreciate the charm of the place. You will not feel it unless you are persuaded here for a little that all the tragedies and cares of the world are the things of a dream.

But this spot, which might be called, as part of it is, the Glen of Good Fortune, is excepted from the mournful and wild Kingdom of Kerry. It is a spot of light in the darkness. Behind its rich woods stand bare heights, Mangerton, Carrantual, and Cromaglen, and just above it that changing river is darkened by the Gap of Dunloe. If you should ascend that river to its neighbouring source, you would find yourself under Cruacha Dhu, the Black Reeks, and in the heart of a wilderness where the gloom is primeval. And the people of the Kingdom of Kerry, the few representatives of its desperate clans, have in their nature much that is primitive. If you can get to know them at all (and that is not easy) you will feel that the first wandering men who found their westward course limited on this brink of the world must have resembled them. They have never been understood by their neighbours, and in consequence they have seldom been trusted. Perhaps the distrust arose partly because they were suspicious. So were the primeval men: one can imagine them dark and silent and only gregarious because they were afraid. There is no doubt that the world was born old. And along these shores you will find in mature people the first solemnity of infants.

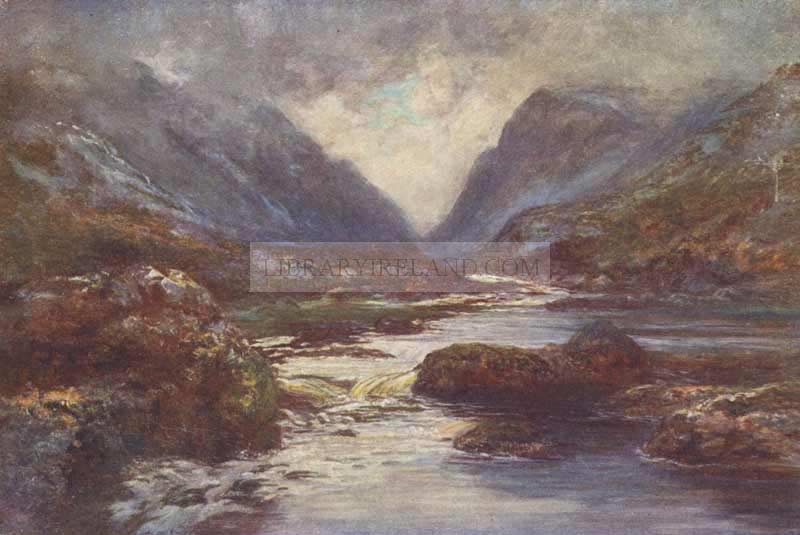

THE GAP OF DUNLOE

KILLARNEY owes its world-wide reputation as much to the variety as to the beauty of its scenery. We find here a combination of all kinds, wonderfully contrasting with each other—from the wildest rugged mountain to the gentlest sylvan glade, from the swift river to the placid lake bordered with foliage-covered hills: to all these beauties the Gap of Dunloe is the gate.

This is a land less shadowed by heights than Connemara, less stern than Donegal. It has more numerous green and happy recesses than either; for if you follow its loud shore, you will come on many such glades as Glengariff, Parknasilla, and Caragh; but these, like Killarney, derive most of their charm from the lonely and dim places behind them. Donegal and Connemara are grim; but in these Highlands, scourged though they are by tempests and thrilled by the perpetual thunder of the heavy waves, you find the first peace that is so akin to the last peace of despair.