The Legend of Knockfierna - Fairy Legends of Ireland

T is a very good thing not to be any way in dread of the fairies, for without doubt they have then less power over a person; but to make too free with them, or to disbelieve in them altogether, is as foolish a thing as man, woman, or child can do.

It has been truly said that "good manners are no burthen," and that "civility costs nothing;" but there are some people foolhardy enough to disregard doing a civil thing, which, whatever they may think, can never harm themselves or any one else, and who at the same time will go out of their way for a bit of mischief, which never can serve them; but sooner or later they will come to know better, as you shall hear of Carroll O'Daly, a strapping young fellow up out of Connaught, whom they used to call, in his own country, "Devil Daly."

Carroll O'Daly used to go roving about from one place to another, and the fear of nothing stopped him; he would as soon pass an old churchyard or a regular fairy ground, at any hour of the night, as go from one room into another, without ever making the sign of the cross, or saying, "Good luck attend you, gentlemen."

It so happened that he was once journeying in the county of Limerick, towards "the Balbec of Ireland," the venerable town of Kilmallock; and just at the foot of Knockfierna he overtook a respectable-looking man jogging along upon a white pony. The night was coming on, and they rode side by side or some time, without much conversation passing between them, further than saluting each other very kindly; at last, Carroll O'Daly asked his companion how far he was going.

"Not far your way," said the farmer, for such his appearance bespoke him: "I'm only going to the top of this hill here."

"And what might take you there," said O'Daly, "at this time of the night?"

"Why, then," replied the farmer, "if you want to know, 'tis the good people!"

"The fairies, you mean," said O'Daly. "Whist! whist!" said his fellow-traveller, or "you may be sorry for it;" and he turned his pony off the road they were going towards a little path which led up the side of the mountain, wishing Carroll O'Daly good-night and a safe journey.

"That fellow," thought Carroll, "is about no good this blessed night, and I would have no fear of swearing wrong if I took my Bible oath that it is something else beside the fairies, or the good people, as he calls them, that is taking him up to the mountain at this hour. The fairies!" he repeated; "is it for a well-shaped man like him to be going after little chaps like the fairies? To be sure, some say there are such things, and some say not; but I know this, that never afraid would I be of a dozen of them, ay, of two dozen, for that matter, if they are no bigger than what I hear tell of."

Carroll O'Daly, whilst these thoughts were passing in his mind, had fixed his eyes steadfastly on the mountain, behind which the full moon was rising majestically. Upon an elevated point that appeared darkly against the moon's disc, he beheld the figure of a man leading a pony, and he had no doubt it was that of the farmer with whom he had just parted company.

A sudden resolve to follow flashed across the mind of O'Daly with the speed of lightning: both his courage and curiosity had been worked up by his cogitations to a pitch of chivalry; and muttering, "Here's after you, old boy," he dismounted from his horse, bound him to an old thorn tree, and then commenced vigorously ascending the mountain.

Following as well as he could the direction taken by the figures of the man and pony, he pursued his way, occasionally guided by their partial appearance: and after toiling nearly three hours over a rugged and sometimes swampy path, came to a green spot on the top of the mountain, where he saw the white pony at full liberty, grazing as quietly as may be. O'Daly looked around for the rider, but he was nowhere to be seen; he however soon discovered close to where the pony stood an opening in the mountain like the mouth of a pit, and he remembered having heard, when a child, many a tale about the "Poul-duve," or Black Hole of Knockfierna; how it was the entrance to the fairy castle which was within the mountain; and how a man, whose name was Ahern, a land sur-veyor in that part of the country, had once attempted to fathom it with a line, and had been drawn down into it, and was never again heard of; with many other tales of the like nature.

"But," thought O'Daly, "these are old women's stories; and since I've come up so far I'll just knock at the castle door, and see if the fairies are at home."

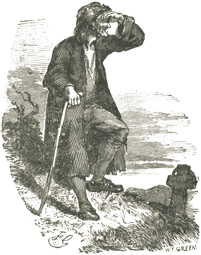

No sooner said than done; for seizing a large stone as big, ay, bigger than his two hands, he flung it with all his strength down into the Poul-duve of Knockfierna. He heard it bounding and tumbling about from one rock to another with a terrible noise, and he leant his head over to try and hear if it would reach the bottom—when what should the very stone he had thrown in do but come up again with as much force as it had gone down, and gave him such a blow full in the face that it sent him rolling down the side of Knockfierna head over heels, tumbling from one crag to another, much faster than he came up; and in the morning Carroll O'Daly was found lying beside his horse, the bridge of his nose broken, which disfigured him for life, his head all cut and bruised, and both his eyes closed up, and as black as if Sir Daniel Donnelly had painted them for him.

Carroll O'Daly was never bold again in riding alone near the haunts of the fairies after dusk; but small blame to him for that; and if ever he happened to be benighted in a lonesome place he would make the best of his way to his journey's end, without asking questions or turning to the right or to the left, to seek after the good people, or any who kept company with them.

Eagle's Nest, Killarney