[From the Dublin Penny Journal, Vol. 1, No. 7, August 11, 1832]

The Dublin Society originated in the year 1731, in the private meetings of a few eminent men, and was supported solely by their subscriptions for eighteen years. It received a charter from George II. and has been liberally supported by various annual grants from Parliament, although latterly it has shared a diminution of income, along with every other society in Ireland.

In the year 1815, the splendid mansion of the Duke of Leinster in Kildare street was purchased by the society for £20,000. This noble building is worthy of the purposes for which it is assigned. A gateway of rustic masonry leads from Kildare street into a spacious court, forming an immense segment of a circle before the principal front, which is 140 feet long by 70 deep. The Hall is spacious and lofty, and contains a number of statues, of which a description will be given when we come to Sculpture. Our object at present is at once to enter the Museum, which is thrown open to the public every Monday and Friday, from 12 to three o'clock; though at present it is partially closed on account of the prevalence of cholera.

The civility and politeness of the Museum keeper must be extremely gratifying to every stranger who visits the rooms. Every thing worthy of attention is explained, nay, expatiated on; and you feel quite at ease in listening to an individual, when conscious that no fee is expected, and that he is not measuring his descriptions by the conjectural length of your purse. It renders one happy in wandering amid the various and multifarious objects with which the rooms are garnished-you can walk from bird to beast, and from beast to reptile, and from reptile to shells, minerals, monstrosities, every thing rich and rare, ever thing wonderful, curious, and incomprehensible - without an abridgment of the happiness enjoyed. And what a fund of materials are here, for meditation and reflection! Butterflies, beetles, and bats - mummies from Egypt and tatooed heads from New Zealand - Greenland huts and Arabian rocks - boa constrictors and birds of Paradise - earth, sea, and air have given out their treasures - the torrid and the frigid zones have contributed to enrich the Museum. But it would be a vain attempt to give a general description, in one article, of the various objects to be seen at the rooms. It would just be similar to one hurried visit, of which no permanent impression is left upon the mind. The objects to be seen are too numerous to be remembered with any degree of precision; and the unpractised visitor should endeavour to go as often as he can, to fix his attention on a few objects at a time, and endeavour to classify in his mind whatever may be worthy of particular observation; and thus will his ideas be concentrated - his knowledge extended and improved. After the same plan will we proceed, and selecting remarkable and particular objects, present them from time to time to our readers.

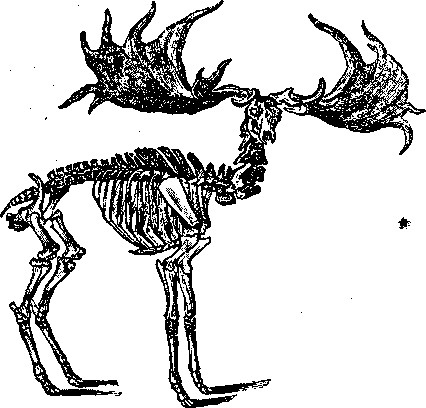

The object which first arrests observation on entering, is the magnificent skeleton of the fossil deer, standing in the centre of the room.

This splendid relic of the former grandeur of the animal kingdom, was dug up at Rathcannon, near Limerick, and presented to the Dublin Society by Archdeacon Maunsel. It is perfect in every single bone of the frame work which contributes to form a part of its general outline; and surmounted by the head and beautifully expanded antlers, which extend out to a distance of SIX FEET on either side, it is calculated to excite the most elevated ideas of its majestic appearance; and when the reader recollects that from the ground to the highest point of the tip of the antler is ten feet, four inches, and that from the end of the nose to the tip of the tail, it is ten feet, ten inches, his imagination will most naturally be carried back to the time when whole herds of this noble animal ranged over the country; and when we contrast it with the Lilliputian things that skip in the Phoenix Park, an involuntary regret will arise in the mind that the race should be so totally extinct.

When and where, did this gigantic species of deer exist? Such is the question which arises at once to every man's mind-yet nothing but mere conjecture can be given in reply. No tradition of its actual existence remains: yet so frequently are bones and antlers of enormous size dug up in the various parts of the island, that the peasantry are acquainted with them as the "old deer" and in some places these remains are so numerous and so frequent that they are often thrown aside as useless lumber. A pair of these antlers were used as a field gate near Tipperary. Another pair had been used for a similar purpose near Newcastle, in the county of Wicklow, until they were decomposed by the action of the weather. There is also a specimen in Charlemont House, the town residence of the Earl of Charlemont, which is said to have been used for some time as a temporary bridge across a rivulet in the county Tyrone. Now, though similar remains have been found in Yorkshire, on the coast of Essex, in the isle of Man, in different parts of Germany, in the forest of Bondi, near Paris, and in some parts of Lombardy, it is evident that the animal had its favourite haunts in our fertile plains and vallies, and has some claim to the title of the Irish fossil deer. Thus one part of the question is answered-we can tell where 'the animal existed, as far as extreme probability can go, but as to when, it baffles our investigations.

What could be the use of the immense antlers with which the animal was furnished? It is evident that they would prevent it from making any progress through a country thickly wooded with trees, and that the long, tapering, pointed antlers were totally unfit for lopping off the branches of trees, a use to which the elk sometimes applies his antlers, and for which they seem well calculated. It is said that the elk, when pursued in the forests of America, will break off branches of trees as thick as a man's thigh. But the antlers of the fossil deer seem to have been given to it for its protection, a purpose for which they, doubtless, have been admirably designed; for their lateral expansion is such, that, should occasion require the animal to use them in his defence, their extreme tips would easily reach beyond the remotest parts of his body; and when we consider the powerful muscles for moving the head, with the length of the lever afforded by the antlers themselves, we can easily conceive that he could wield them with a force and velocity which would deal destruction to any enemy having the hardihood to venture within their range.

There is presumptive evidence that man existed at the same period with this animal - one proof of which seems to be in a rib of the deer (presented to the Society by the same gentleman who presented the skeleton,) and which has evidently been perforated with an arrow, or some similar sharp pointed instrument. It is not improbable that the chase of this gigantic creature formed part of the business and pleasure of the then inhabitants of the country, and that amongst its enemies might be included the wolf, and the celebrated Irish wolf dog.

This account has been compiled from a little pamphlet by Dr. Hart, which was drawn up at the instance of the Committee of Natural Philosophy of the Royal Dublin Society.