Kilmallock

[From the Dublin Penny Journal, Vol. 1, No. 9, August 25, 1832]

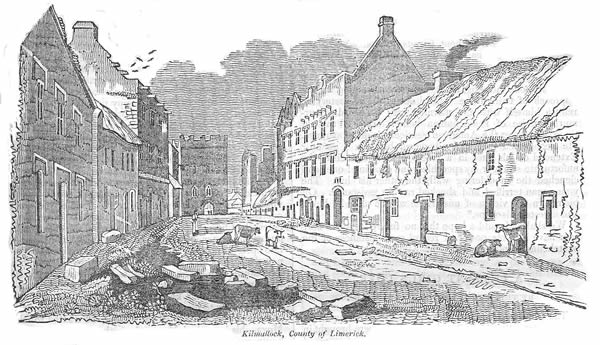

Kilmallock, County of Limerick.

A few years since, Kilmallock presented to a reflecting and imaginative mind, a scene of singular, and we might add, intensely romantic interest-that of a noble town, walled, turreted, and tilled with stately monasteries, castles, and houses of cut stone, all ruined, silent, and deserted; some wretched peasants had indeed here and there taken up their residence in the corner of a tower or mansion, which, like a solitary figure in a mountain scene, only added to the effect of sadness and desolation. It was at this period that the prefixed sketch was made: Kilmallock has since assumed a different aspect: it has become again a scene of life and animation, and though it has lost much of its poetic and pictorial interest, it will give greater pleasure to the eye of the philanthropist.

Kilmallock has been a place of some distinction from a very remote period, and like most of our ancient towns is of ecclesiastieal origin, a monastery having been founded here by St. Maloch in the 6th century, of which the original round tower still remains. It is said to have been a walled town even before the arrival of the Anglo Normans, but at all events it became a place of great strength and celebrity under the Desmond branch of the Geraldines, and ranked as their chief town. Much, however, of its present ruined magnificence is of a period subsequent to the fall of that great family, as the majority of the houses are of the reign of the 1st James, and none of them earlier than that of Elizabeth, when stone mansions first came into use in the chief towns in Ireland. Many of the castles, and the gates, and the surrounding walls, are however connected with the Geraldine power.

Kilmallock has been designated "the Irish balbec" by Dr. Campbell, a writer of considerable learning and some imagination; and this high sounding epithet is not undeserved, if properly understood as applying only to a great assemblage of Irish ruins, as their magnificence will of course bear but little comparison with those of the Eastern city. These consist at present chiefly of a street of stone built houses, frequently of three stones in height, and having windows and doorways of cut stone; the former have stone sashes called by architects, mullions, and label mouldings, and the latter are usually arched. These houses have also curious and grotesque spouts, and above the first story, frequently an ornamented architrave, in this style.

There were anciently four great entrance gateways of lofty and imposing character, of which two still remain; and there are also some smaller towers remaining in the surrounding town walls. Outside the town, and on the banks of the beautiful stream called the Cammogue, stand the ruins of two truly splendid monasteries, in which there are several curious and interesting sepulchral monuments: of these, we shall give our readers a view and description in a future number, together with an account of the last chiefs of the Desmonds, the ancient lords of the place, with whose history Kilmallock is so intimately connected.

Kilmallock has been in a state of desolation and decay since the time of the usurper Cromwell, when it was dismantled and otherwise greatly injured by the parliamentary army. The recent return of population is fast hastening the devastations of time, and, excepting its ecclesiastical remains, in a few years it will have but little vestiges of its former splendour. Antiquarians as we are, however, we shall regret this change but little, if it bring industry, wealth, and peace, to a spot that has been for a long period the dreary abode of wretchedness and want. Of its sufferings during the year 1817, when typhus fever raged so frightfully in the South of Ireland, take the following anecdote from the interesting tour of the unfortunate J. B. Trotter - the truth of the circumstances here detailed, may be relied on: -

"In one part of the ruins, where a fine arched side-aisle was still very perfect, my guide showed some terror: I soon learned from him the cause. A person ill of fever had been left there the day before, lest he should communicate the infection to the family where he lodged. He was left to expire! His hollow voice plaintively implored some drink; I assured him he should have it, and be taken care of, and hope revived at the moment life was ebbing fast away. In another part of this monastery I saw a hat of a departed victim of fever exposed some time ago, and at our Inn I heard the following story:-An American gentleman, totally a stranger, well clad and of pleasing appearance, came a few months ago to Kilmallock. He went to no inn, but wandered about the ruins, till at last entering them he was observed no more, and perhaps forgotten! He was ill, and fever burned in his veins; but where can a pennyless and forlorn wanderer turn in a country where he is without friends or money? It happened that a gentleman was ill at the inn, and required the attendance of a person to sit up every night. The innkeeper's son performed this humane office frequently; and very early one morning, as the stars were fading at the approach of twilight, he walked out to the monastery to refresh himself with the morning air; he heard a murmuring noise of some human being. It was two or three days after the American gentleman's disappearance. He recollected this, and advanced, but can I go on? Extended on his back in a recess of a ruined aisle, the unfortunate stranger lay speechless and expiring! one hand clenched the mouldering wall, the other his hat. The young man terrified and shocked ran for assistance. On his return this victim of misfortune was no more! Fever had arrested his steps."

We shall only add a hope that no future traveller may ever have it in his power to record such instances of the wretchedness and inhumanity of Kilmallock.