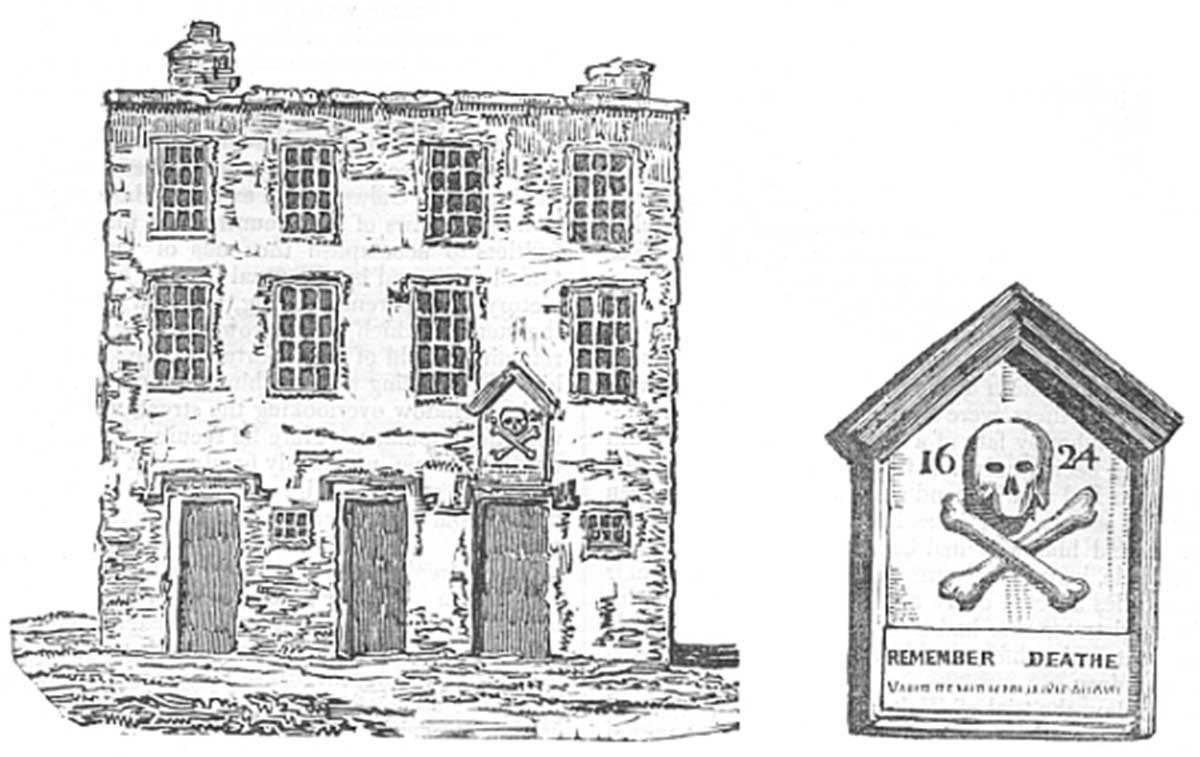

Lynch’s House and Tablet over the Doorway, Galway

There are few, if any, of our readers, who are unacquainted with the story of the Warden of Galway—the subject of an interesting legend in the very valuable history of that town by Mr. Hardiman, and of an excellent tragedy by our fellow-citizen, the Rev. Edward Groves.

The wood-cuts prefixed, according to Mr. Hardiman, represent the house of that Brutus-like magistrate, and the tablet which the historian supposes was subsequently put over the doorway to commemorate the tragical event.

With the love for truth which, we trust, will always be found to pervade the pages of our little Journal, we confer that we are somewhat sceptical as to the truth of a circumstance of which no historical evidence has been as yet adduced; and as antiquarians, we altogether deny the house to be of the antiquity assigned to it—namely, the fifteenth century.

The date over its doorway, 1624, is unquestionably the true period of its erection. Stone houses were not known in Ireland at the time which Mr. Hardiman supposes this to have been erected. The emblem and motto prove nothing, for religious and moral sentences are usual on the domestic edifices of that age.

We present our readers with the legend in a somewhat abridged form, which, though published more than once, will doubtless amuse them.

P.

A few years before the battle of Knocktuadh, an extraordinary instance of civic justice occurred in this town, which in the eyes of its citizens elevated their chief magistrate to a rank with the inflexible Roman. James Lynch Fitz-Stephen, an opulent merchant, was mayor of Galway in 1493. He had made several voyages to Spain, as a considerable intercourse was then kept up between that country and the western coast of Ireland.

When returning from his last visit he brought with him the son of a respectable merchant named Gomez, whose hospitality he had largely experienced, and who was now received by his family with all that warmth of affection which from the earliest period has characterised the natives of Ireland.

Young Gomez soon became the intimate associate of Walter Lynch, the only son of the mayor, a youth in his twenty-first year, and who possessed qualities of mind and body which rendered him an object of general admiration; but in these was unhappily united a disposition to libertinism, which was a source of the greatest affliction to his father.

The worthy magistrate, however, was now led to entertain hopes of a favourable change in his son’s character, as he was engaged in paying honourable addresses to a beautiful young lady of good family and fortune.

Preparatory to the nuptials, the mayor gave a splendid entertainment, at which young Lynch fancied his intended bride viewed his Spanish friend with too much regard. The fire of jealousy was instantly lighted up in his distempered brain, and at their next interview he accused his beloved Agnes of unfaithfulness to him. Irritated at its injustice, the offended fair one disdained to deny the charge, and the lovers parted in anger.

On the following night, while Walter Lynch slowly passed the residence of his Agnes, he observed young Gomez to leave the house, as he had been invited by her father to spend that evening with him. All his suspicions now received the most dreadful confirmation, and in maddened fury he rushed on his unsuspecting friend, who, alarmed by a voice which the frantic rage of his pursuer prevented him from recognising, fled towards a solitary quarter of the town near the shore.

Lynch maintained the fell pursuit till his victim had nearly reached the water’s edge, when he overtook him, darted a poniard into his heart, and plunged his body, bleeding, into the sea, which, during the night, threw it back again upon the shore, where it was found and recognised on the following morning.

The wretched murderer, after contemplating for a moment the deed of horror which he had perpetrated, sought to hide himself in the recesses of an adjoining wood, where he passed the night a prey to all those conflicting feelings which the loss of that happiness he had so ardently expected, and a sense of guilt of the deepest dye, could inflict.

He at length found some degree of consolation in the firm resolution of surrendering himself to the law, as the only means now left to him of expiating the dreadful crime which he had committed against society.

With this determination he bent his steps towards the town at the eailiest dawn of the following morning; but he had scarcely reached its precincts, when he met a crowd approaching, amongst whom, with shame and terror, he observed his father on horseback, attended by several officers of justice.

At present, the venerable magistrate had no suspicion that his only son was the assassin of his friend and guest; but when young Lynch proclaimed himself the murderer, a conflict of feeling seized the wretched father beyond the power of language to describe.

To him, as chief magistrate of the town, was entrusted the power of life and death. For a moment the strong affection of a parent pleaded in his breast in behalf of his wretched son: but this quickly gave place to a sense of duty in his magisterial capacity as an impartial dispenser of the laws.

The latter feeling at length predominated, and though he now perceived that the cup of earthly bliss was about to be for ever dashed from his lips, he resolved to sacrifice all personal considerations to his love of justice, and ordered the guard to secure their prisoner.

The sad procession moved slowly towards the prison amidst a concourse of spectators, some of whom expressed the strongest admiration at the upright conduct of the magistrate, while others were equally loud in their lamentations for the unhappy fate of a highly accomplished youth who had long been a universal favourite.

But the firmness of the mayor had to withstand a still greater shock when the mother, sisters, and intended bride of the wretched Walter beheld him who had been their hope and pride, approach pale, bound, and surrounded with spears. Their frantic outcries affected every heart except that of the inflexible magistrate, who had now resolved to sacrifice life with all that makes life valuable rather than swerve from the path of duty.

In a few days the trial of Walter Lynch took place, and in a provincial town of Ireland, containing at that period not more than three thousand inhabitants, a father was beheld sitting in judgment, like another Brutus, on his only son; and, like him, too, condemning that son to die, as a sacrifice to public justice.

Yet the trial of the firmness of the upright and inflexible magistrate did not end here. His was a virtue too refined for vulgar minds: the populace loudly demanded the prisoner’s release, and were only prevented by the guards from demolishing the prison, and the mayor’s house, which adjoined it; and their fury was increased on learning that the unhappy prisoner had now become anxious for life.

To these ebullitions of popular rage were added the intercessions of persons of the first rank and influence in Galway, and the entreaties of his dearest relatives and friends; but while Lynch evinced all the feeling of a father and a man placed in his singularly distressing circumstances, he undauntedly declared that the law should take its course.

On the night preceding the fatal day appointed for the execution of Walter Lynch, this extraordinary man entered the dungeon of his son, holding in his hand a lamp, and accompanied by a priest. He locked the grate after him, kept the keys fast in his hand, and then seated himself in a recess of the wall.

The wretched culprit drew near, and, with a faltering tongue, asked if he had any thing to hope? The mayor answered,

“No, my son—your life is forfeited to the laws, and at sun-rise you must die! I have prayed for your prosperity: but that is at an end—with this world you have done for ever—were any other but your wretched father your judge, I might have dropped a tear over my child’s misfortune, and solicited for his life, even though stained with murder; but you must die: these are the last drops which shall quench the sparks of nature; and, if you dare hope, implore that heaven may not shut the gates of mercy on the destroyer of his fellow-creature. I am now come to join with this good man in petitioning God to give you such composure as will enable you to meet your punishment with becoming resignation.”

After this affecting address, he called on the clergyman to offer up their united prayers for God’s Forgiveness to his unhappy son, and that he might be fully fortified to meet the approaching catastrophe. In the ensuing supplications at a throne of mercy, the youthful culprit joined with fervor, and spoke of life and its concerns no more.

Day had scarcely broken when the signal of preparation was heard among the guards without. The father rose, and assisted the executioner to remove the fetters which bound his unfortunate son. Then unlocking the door, he placed him between the priest and himself, leaning upon an arm of each. In this manner they ascended a flight of steps lined with soldiers, and were passing on to gain the street, when a new trial assailed the magistrate, for which he appears not to have been unprepared.

His wretched wife, whose name was Blake, failing in her personal exertions to save the life of her son, had gone in distraction to the heads of her own family, and prevailed on them, for the honour of their house, to rescue him from ignominy. They flew to arms, and a prodigious concourse soon assembled to support them, whose outcries for mercy to the culprit would have shaken any nerves less firm than those of the mayor of Galway.

He exhorted them to yield submission to the laws of their country; but finding all his efforts fruitless to accomplish the ends of justice at the accustomed place and by the usual hands, he, by a desperate victory over parental feeling, resolved himself to perform the sacrifice which he had vowed to pay on its altar.

Still retaining a hold of his unfortunate son, he mounted with him by a winding stair within the building, that led to an arched window overlooking the street, which he saw filled with the populace. Here he secured the end of the rope which had been previously fixed round the neck of his son, to an iron staple, which projected from the wall, and, after taking from him a last embrace, he launched him into eternity.

The intrepid magistrate expected instant death from the fury of the populace; but the people seemed so much overawed or confounded by the magnanimous act, that they retired slowly and peaceably to their several dwellings.

The innocent cause of this sad tragedy is said to have died soon after of grief, and the unhappy father of Walter Lynch to have secluded himself during the remainder of his life from all society, except that of his mourning family.

His house still exists in Lombard-street, Galway, which is yet known by the name of “Dead Man’s Lane,” and over the front doorway are to be seen a skull and cross bones executed in black marble, with the motto, “Remember Deathe, vaniti of vaniti, and all is but vaniti.”