Sir Walter Scott's Visit to Ireland.

From The Dublin Penny Journal, Volume 1, Number 25, December 15, 1832.

The general life of Sir Walter Scott, does not properly come within the

objects of our Journal, and besides must be already familiar to most of

our readers; but there is one portion of it which belongs peculiarly to

our country, and which has been but little noticed hitherto -- his

first and only visit to Ireland, in the summer of 1825.

The general life of Sir Walter Scott, does not properly come within the

objects of our Journal, and besides must be already familiar to most of

our readers; but there is one portion of it which belongs peculiarly to

our country, and which has been but little noticed hitherto -- his

first and only visit to Ireland, in the summer of 1825.

That he had long viewed Ireland with feelings of considerable interest, there can be little doubt; deeply engaged in antiquarian research, his attention could hardly have failed to be arrested by her well known claim to the highest antiquity, and still further by the connexion of her ancient history with that of Scotland. He had, besides, many old and valued friends here, who had long and urgently solicited him to visit them; and at length his son, (the present Sir Walter Scott,) to whom he was much attached, being quartered in Dublin with his regiment, the 15th Hussars, affording an additional inducement, on the 14th July, 1825, Scott arrived accompanied by Mr. Lockhart, his son-in-law, and his daughter, Miss Scott.

Our national poet, Moore, was expected in Dublin about this time, but he did not arrive during Scott's stay. Mr. Hallam, the talented historian of the "Middle Ages," was in Ireland, but was just at that time engaged in a tour through some of the northern counties. Sir Humphrey Davy, and the learned Dr. Adam Clarke, were indeed here, but the former appears to have been engaged with the promotion of his brother's election to the office of Professor of Chemistry to the Dublin Society, about which he had come from England, and the latter with the performance of his clerical functions among the Society of Methodists, to which he belonged, and accordingly neither of them appear to have met Scott in society during the short period of his sojourn in this country.

For nearly a fortnight after his arrival, Scott was occupied in viewing the public buildings and institutions of Dublin. Among the rest, St. Patrick's Cathedral, so closely connected with his editorial labours and recollections of Swift, attracted his earliest attention; he lingered long before the monumental tablet erected to Swift's memory, and with much feeling translated to the ladies who accompanied him, the nervous Latin epitaph inscribed on it, which records, in Swift's own words, his hatred of oppression, and exertions in the cause of liberty. The humble memorial of Mrs. Hester Johnson, (the unfortunate Stella,) did not escape his notice; nor a small slab which Swift placed near the southern entrance, anciently called St. Paul's gate, in memory of the "discretion, fidelity, and diligence" of his faithful servant, Alexander M'Gee. At the Deanery House he was shown the fine full-length original portrait of Swift, which is preserved there, having been painted by Bindon, in the year 1738, at the expense of the Chapter, whose property it is.

In passing from the Deanery to the adjacent library, founded by Dr. Marsh, Scott was shown the ancient residence of the Archbishops of Dublin, which however was not deemed worth a visit, as the exterior of the building alone retains any interest, it having been some time previously converted into a barrack for the horse police of the city. In Marsh's library he was much interested and amused by some marginal autograph notes, written, chiefly in pencil, in Clarendon's History of the Rebellion, by Swift in his most caustic and abusive style, containing the fiercest invectives against the Scottish nation. His notice was also called by the librarian to a desk of rather rude workmanship, which had been long used there by his deceased friend, Maturin, who being in the habit of reading in this library for several hours every day, had with his own hands constructed this little desk for his convenience. On this, it is said, the greater part of his novel of "The Albigenses," as well as some others of his works had been written. Of Maturin's genius Scott had long entertained the very highest opinion; they had corresponded for a long time, and he had invited Maturin to Abbotsford, but it does not appear that they ever met. To his widow, Scott hastened to pay an early visit of condolence, and endeavoured to mitigate her sorrows by an act of munificent generosity. He had previously offered, in the most friendly manner, to edite Maturin's Novels, or selections from them, with an introduction by himself, on his return home from Ireland; but before he could carry his intentions into effect, the disastrous consequences of his connexion with the house of Constable and Co., which met him almost on his arrival in Scotland, compelled him to relinquish his design, and he wrote back to Mrs. Maturin in the kindest terms, assuring her that nothing but the imperative necessity of devoting his exclusive attention and energies to his own pressing affairs, should have made him give up the task he had undertaken.

While Scott was in Dublin, he hoped to have been able to make some valuable additions to his library, of rare books and tracts relating to Irish history, which he supposed he would more probably have met with here than else where; and he was accordingly indefatigable in his search at shops and standings where second-hand books are sold. More than once he sallied out by himself, at an early hour after breakfast, on this quest. Upon one occasion he was observed to remain at a book-standing upon the quay, leading to the Custom House, for a considerable while, nearly a quarter of an hour, and during that time he never took down a single book from its place, or even removed his hands from behind his back, contenting himself with patiently and carefully going over the titles of the books inscribed on their backs. He expressed much disappointment at being totally unsuccessful in his search; and, in despair at his ill-fortune, he went the day before he quitted Ireland, to the shop of Mr. Milliken, the bookseller, in Grafton-street, and there expended upwards of £60 in the purchase of books relating solely to the history and antiquities of this country.

For some time before his visit to Ireland, a very general notion prevailed that he was the author of the celebrated Waverley Novels, and this idea certainly was far from diminishing the popularity he had acquired by his previously acknowledged works. This was most strikingly manifested in Dublin, not only at the Theatre, where he was compelled by the reiterated calls of a crowded audience, to come forward and return thanks for this flattering welcome, but also through the streets, where his carriage was followed by crowds in every direction, who pursued it, anxious to catch a glimpse of him from whose writings they had derived such gratification. It is said he was much pleased, as indeed was most natural, by these unequivocal demonstrations of public estimation and favour.

Various tokens of respect and esteem now poured in from every quarter on the distinguished stranger; of many invitations he accepted, but they were invariably from private individuals; those from public bodies were politely but firmly declined. The freedom of the Guild of Merchants was conferred upon him soon after his arrival, a deputation from the Guild having waited upon him at his house in Stephen's-green for the purpose; and soon after he was presented by the University with the degree of Doctor of Laws. He had also, some time before, been elected an honorary member of the Royal Irish Academy, and on the occasion of his visiting Cork, on his return from his tour in the south of Ireland, he was granted the freedom of that city at the same time with Major General Sir George Bingham, Admiral Plampin, and Mr. Sergeant Lefroy. He paid a visit of some days at Old Connaught, the hospitable residence of the Lord Chancellor, then Mr. Plunkett; shortly afterwards he dined with the Lord Lieutenant, (Lord Wellesley,) at Malahide Castle, where he resided for his health during the summer.

The first excursion Scott made to the country, was to the County of Wicklow, several of the most picturesque spots of which he rapidly visited. No beauty of sylvan scenery, however, seems to have arrested his attention, or excited his interest in the same degree as the ecclesiastical ruins at Glendalough, Holycross, and the Rock of Cashel. At "that inestimably singular scene of Irish antiquities," as he afterwards termed it in an article in the Quarterly, the "Seven Churches at Glendalough," he remained an entire day, with great apparent pleasure, and examined these mouldering monuments of the ancient monastic splendour of Ireland, with an excited enthusiasm which appeared extraordinary to the companions of his tour, to whom he frequently observed that he had never before seen ecclesiastical remains of equal antiquity or interest. He also, with all the ardour of a youthful mind, despite his lameness, boldly ascended the cliff, and entered that extraordinary hermit's cell, called St. Kevin's Bed; and after the fashion of its visiters, inscribed his name upon the rock as a memorial of his daring.

Stopping at the inn, at Roundwood, he sent for the well known Judy, and entered into some conversation with her; the circumstances of which interview she since details with great delight to many an attentive auditory; and before dismissing her, he gave her a more substantial cause to remember his visit than mere words.

The wild and rocky scenery of some parts of the Wicklow mountains proximate to Dublin, reminded him of some of the scenes of his native Scotland. From the Phoenix Park, where he was present at a Review of part of the Garrison, he had already noted these mountains, forming, as he said, "a beautiful screen" along the southern boundary of the county.

There is a spot about four miles distant from Dublin, on the mountain road to Glancree, from which a singularly interesting view of our city is obtained; to this Scott's attention was directed by a friend who was with him. The place we allude to is one of almost desert wildness; nothing but heath and rock surround the spectator; while before him is extended, in all the pride of cultivation, and dotted all over with villas and beautifully wooded demesnes, the fertile plain in which Dublin is situated: Spread along the entire horizon lies the city, its spires and lofty buildings rising from among its less distinguished structures, till on the right, Howth, and the magnificent Bay of Dublin, terminate the prospect. Struck with the sudden transition from the lonely and desert heath to the cultivated and busy plain, he expressed, energetically, his surprise at the contrast, one so remarkable as which, he said, he had never before taken in at a glance.

It happened that rather a singular circumstance took place before he had well quitted the spot. He was at the time on his way with one of the most intimate and valued of his friends, about to make a short visit to a beautiful little rustic villa he had built in the very wildest part of these rugged and desert hills, on the verge of the singularly picturesque mountain lake of Lough Bray; and the carriage was stopped while they alighted to admire the remarkable features of the landscape to which we have just alluded. As they were about to resume their journey, they perceived a vast number of the peasantry appearing suddenly on the surrounding hills; nearer to them, women and children rushing out of the houses, and an unusual commotion evidently taking place. A small detachment of police were on the road, evidently remonstrating with some of the people, and presently a troop of Dragoons galloped up. As they approached the place where the police stood, they perceived them endeavouring to persuade the people to separate and return to their houses peaceably. One fellow, however, resisted more strenuously than the rest, perhaps under the influence of valour-inspiring whiskey, and opposed himself to the police with all the characteristic hardihood of his countrymen; he threw open his coat, exposing his bared breast to their bayonets, which however they were far from attempting to use, and, with the most frantic gesticulations, he called out, "Kill me now, do!--arrah, why don't ye kill me?--just do, now; kill me if you dare!"----One of the police calmly thrust him back with his hands, and his wife and some other females clinging about him, gradually took him away. The whole terminated quite peaceably in a short time. The people, overawed, retreated to their homes, and the military and police soon drew off. A short explanation sufficed to clear up the matter. There had been a turn-out of the workmen of an extensive paper factory in the neighbourhood, established there by a Mr. Pickering, which gave employment to numbers of the peasantry of the surrounding country, and, in consequence of some difference with their employer, they had threatened the demolition of his factory, which they possibly would have effected but for the timely interference of a protecting force. While this explanation was being obtained, Scott gravely turned round to his host, and with infinite humour thanked him most warmly for all his hospitality and solicitude for his entertainment since his arrival in Ireland, and added, that above all he felt indebted to him for his kindness in having so obligingly got up a little rebellion for his especial amusement.

The situation of Lough Bray is very remarkable; embosomed in the mountains, which almost on every side overhang it precipitously, its vicinity is quite imperceptible to the stranger, till a sudden turn in the road abruptly presents it in all its wildness and solitary beauty. "Ah," said Scott, the moment he caught the first view of it, "this is surely the lake of the Arabian tale, where the enchanted fish were, of the situation of which it appeared so incredible to the Sultan and his Vizier that they should be ignorant, it being but a short distance from their capital."

The amazing retentiveness and fidelity of Scott's memory has been often noticed; one instance in which it was very remarkably exhibited about this time has come within our knowledge. It was occasioned by his happening to ask the friend of whom we have been speaking, had he ever heard of a namesake of his, a young Irish officer of great wit and talent, who had been much spoken of in Scotland, where he had been many years quartered with his regiment, and had left behind him some poetical fragments evincing taste and spirit. Scott's friend quickly recognized him as a younger brother of his father's, and in a passing way repeated the following little effusion of his, which he just then happened to recollect.

ON MISS WHITING.

Since Whiting is no fasting

dish,

Let priests say what they dare,

I'd rather have my pretty fish

Than all their Christmas fare!

So gay, so innocent, so free

From all that tends to strife,

Thrice happy man, whose lot shall be

To glide with her through life.

But Venus, goddess of the flood,

Does all my prayers deny,

And surly Mars cries, "D--- your blood,

You've other fish to fry!"

Nothing further was said at the time, but several days afterwards, meeting at the house of a mutual acquaintance, Scott being, after dinner, in the drawing-room, he took his friend's arm, and walking up and down the room, recurred to these verses, and said he nearly remembered all, but wished to be quite certain that he had them correctly. He then rapidly ran them over, but at the line, "So gay, so innocent, so free," he paused, uncertain as to the word "gay," for which he substituted "bright," and this slight difference being corrected, he repeated the whole without the slightest mistake of even a syllable.

The museum of Dr. Tuke, a physician of some eminence in Dublin, which Scott visited about this time, afforded him more gratification than even that of the Royal Dublin Society. At the latter he had vainly looked for a national collection illustrative of Irish antiquities and history, and expressed much disappointment at finding the Museum rather poor in such remains; instead of which he was shown a fine arrangement of minerals, which, as he observed, he was already familiar with in other places; and it is not a little remarkable, that the Russian Archduke Michael, on visiting this museum, expressed a similar disappointment, and stated that he was himself possessed of a much finer and more extensive collection of the Antiquities of Ireland. At Dr. Tuke's house, on the contrary, Scott's anxiety to see some specimens of the weapons, ornaments, &c. of the ancient Irish, was abundantly gratified. He remained there some hours evidently much pleased, and, on his return to Scotland, he sent Dr. Tuke a present of two antique brazen vessels which had been found there, but yet bore considerable resemblance to some of this country, which he had seen in Dr. Tuke's collection.

The following morning (Friday, the 29th,) he left Dublin at an early hour for Edgeworthstown, to pay a long promised visit to our celebrated and talented countrywoman, Miss Edgeworth, who, after he had remained a few days, set out with him on his tour to the Lakes of Killarney The first object of his attention on his arrival there, was the venerable ruin of Mucruss Abbey, which he visited in the afternoon of the day he reached Killarney. The following morning he was early on the water with his party, though the weather was by no means favourable, there being a stiff north-westerly breeze during the greater part of the day, which came in strong gusts down through the mountains surrounding the upper lake, for which they had embarked. They amused themselves for some time waking the slumbering echoes of the rocky cliffs of the Eagle's Nest by the music of the bugle, or the less harmonious, though grander sounds produced by the discharge of small pieces of ordnance, the reiterated reverberations of which exactly resemble a long succession of thunder claps. There were several parties on the Lakes all anxious to catch a glimpse of "the great unknown." After threading the narrow and highly picturesque channel that divides the Upper from Turk Lake, the party landed on Dinis, one of the most beautifully wooded among the innumerable islets of these Lakes, and here they dined. They cannot however be presumed to have been guided in their selection of a place for that repast by the similarity of its name to that of the little island, inasmuch as it is very generally fixed on by parties visiting the Lakes for the same purpose. The following day was occupied by the Lower Lake, O'Sullivan's Cascade, &c., and thus in less than three days Scott despatched his survey of Killarney, which, indeed, seemed to fall short of the expectations he had formed, and at all events failed to draw forth those expressions of enthusiastic pleasure excited by the antiquities of Glendalough and Cashel.

From Killarney he returned to Dublin, visiting in his route, Cork, where, as we have mentioned, the freedom of that city was conferred on him; from thence proceeding by way of Holycross, Cashel, and Johnstown, to Kilkenny. At Cashel, it is said, his purpose had been simply to have changed horses, and during the time occupied by this, to have paid a hurried visit to the celebrated monastic ruins there. But no sooner had he caught a glimpse of this majestic and venerable pile, standing in so striking a position on the summit of a lofty and precipitous rock, than he declared it was quite impossible for him to proceed that day, and a messenger was at once despatched to countermand the horses, and to order dinner; and when asked at what hour he wished it to be on the table, Scott instantly replied, not till after dusk should have rendered it useless to linger longer among the ruins. At Kilkenny Scott made a somewhat longer stay, for the purpose of seeing at leisure the fine old castle, so long the residence of the Ormond family. The following day he was taken to the Convent, the Black Abbey and Cathedral, and afterwards to the celebrated Cave at Dunmore, three miles from the town. It will be remembered that this remarkable Cave, and the noble Castle of Kilkenny, have already been noticed more in detail in the 10th and 11th numbers of our Journal.

On Sunday, the 14th of August, being the anniversary of his birth, Scott entertained a large party of his friends at dinner at his son's house in Stephen's-Green. This was in some degree saddened by the recollection that it was a take-leave party. On the Wednesday following he sailed from Howth, in the Harlequin packet, with the late Captain Skinner, whose melancholy fate his friends, in common with every one by whom he was known, and consequently valued and esteemed, have had so lately to deplore.

It seems that it was a weakness of Scott (a pardonable one, no doubt,) to be a little vain of the coincidence of his birth-day with that of Napoleon; they were born on the same day, the 14th of August, 1771. A similar feeling was excited by the fact of the initials of Shakspeare's name being those of his own. A friend who was staying at Abbotsford happened accidentally to be struck by this coincidence on seeing a bust of Shakespeare in the library, the pedestal of which simply bore the letters W. S.; and, on mentioning to Miss Scott what had occurred to him, she replied that the coincidence had been some time before noticed to her father, and that he appeared not a little pleased at the circumstance. Byron, it is said, in like manner, took pleasure in remarking that the initials of his name, Noel Byron, were the same as those of Napoeon Bonaparte.

There is certainly a great deal about the writings of Scott, and especially his inimitable novels, which cannot fail to remind every one of his great predecessor, and probably, in no slight degree, master in fiction, the mighty and still unrivalled Shakespeare. Whether on the one hand we look at his vast and intimate knowledge of human nature, and of all the various springs of human action, or on the other, his astonishing facility of composition, together with the brilliancy and forcible truth of his delineations of personal character, of the scenery of nature, and the surprising individuality of the actors in his histories, which place so livingly before our mental vision the very bodily shapes of the men he pourtrays; all combine powerfully to bring to our recollection triumphs similar to those of the great dramatist. In this respect, the eulogium of an Italian poet, Anton Franceso Doni, who died in 1574, on the "Novelle Stupende" of Ariosto are strictly applicable to the great novelist.

"Ei ti dipinge una cosa cosi bene,

Che ti pare d'haverla avanti gli occhi,

Con dirti, questa va, quell'altro viene.

Con gl'occhi vedi, e con le man tu tocchri

Cio ch'egli scrive, e con un stil si eletto

Che molti co'l suo dir restano alocchi."

We must however admit, with a writer who long since noticed the striking points of resemblance between those two great masters of the imagination, that Scott is not for a moment to be put in competition with Shakespeare as respects the richness and sweetness of his fancy, or that living vein of pure and lofty poetry which flows with such abundance through every part of his compositions. On that level no other writer has ever stood, or perhaps ever will stand. Notwithstanding, in Scott's works there is, beyond all question, fancy as well as poetry enough, if not fully to justify the comparison between a writer of our own day with the immortal Shakespeare, at least to save such comparison, for the first time for two centuries from being altogether ridiculous.

On leaving Ireland, Scott proceeded to Cumberland, to join a large and distinguished party of visitors at Storrs, the elegant and picturesque residence of Mr. Bolton on the banks of Lake Windermere, among whom not the least eminent was Canning; and after remaining there for but a few days, he returned to Abbotsford.

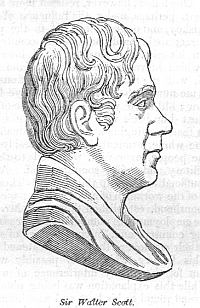

By the kindness of Mr. Weld Hartstonge, we are enabled to give the portrait of Scott, at the head of this article, engraved from a beautiful little medallion head which he himself presented to Mr. Hartstonge many years ago, as a token of friendship. It is the work of an artist of well known ability, Mr. Hennings, the sculptor, modelled in 1813, and has been considered as one of the most faithful transcripts of Scott's features that ever was made.

O'G.