National Biography No.4: Laurence Sterne

From The Dublin Penny Journal, Volume 1, Number 28, January 5, 1833

We can hardly claim Sterne as a countryman. He certainly was born in Ireland, and was here at intervals during part of his childhood; but from the period of his going to school, he never again visited this country. His family too was altogether English, being originally of the county of Suffolk, His great-grandfather was Richard Sterne, Archbishop of York, in the time of Charles II., having been elevated to the archiepiscopal see after the Restoration, in reward for his sufferings and imprisonment during the commonwealth. His son settled at Elvington in Yorkshire. Roger Sterne, the second son of this latter gentleman, and the father of Laurence we find in the most straitened circumstances; a lieutenant in the army, in November, 1713, quartered with his regiment at Clonmel, then a small town in the South of Ireland, where Laurence Sterne was born, as he himself tells us, on the 24th of that month. It has been said that some passages in the life of his parents, and the hardships and poverty with which they had to struggle in maintaining a family on the slender support his father's pay afforded them, furnished Sterne with some hints for his beautiful episode of Le Fevre. His father, having for several years carried his wife and children about with his regiment to various quarters in England and Ireland, they at length enjoyed an interval of repose, remaining for nearly the entire of 1720 in barracks, in the town of Wicklow; from thence they removed to the house of a Mr. Fetherston, a clergyman, who being related to Sterne's mother, invited them to his parsonage, at Annamoe, in the same county. During their stay here, Sterne relates that he had "a wonderful escape in falling through a mill-race whilst the mill was going, and of being taken up unhurt;" "The story," he says, "might be incredible, but was known for truth in all that part of Ireland, where hundreds of the common people flocked to see him." Now to our humble apprehension, the most incredible part of the story is, not that he escaped unhurt; but rather that such a mighty astonishment should have been excited by so simple an occurrence. About the beginning of 1723, his father put him to School at Halifax in Yorkshire, previous to his going out with his regiment to the defence of Gibraltar. During the progress of the siege there, he received a severe wound in a duel with a Captain Phillips, which originated in some quarrel about a goose. With much difficulty he survived, and shortly after being ordered out to Jamaica, whither he went, with an impaired constitution unequal to the hardships he was exposed to, in that climate he was attacked with fever, to which he quickly fell a victim, and died there in March, 1731.

Sterne has recorded an occurrence which took place while he remained at school, and which should not be omitted here. "His master having had the ceiling of the school-room newly white-washed, one unlucky day, the ladder remaining there, he mounted, and wrote with a brush, in large capital letters,--LAU. STERNE;--for which he got a sound whipping from an usher. The master however, was very much hurt at this, and said before him, that never should that name be effaced, for that he was a boy of genius, and would surely come to preferment: this expression made him forget the stripes he had received." We are free to confess, that to us this story appears to exhibit something of that egotistical turn which develops itself also in his relation of his earlier adventure at Annamoe, and is still more preposterously displayed through every part of his correspondence with his friends, published after his death, by his daughter.

To the University of Cambridge, where he was admitted of Jesus College, in 1732, he was sent by his cousin Mr. Sterne of Elvington, who, he says, acted like a father to him; how he occupied himself during his residence there, does not appear. In January, 1736, he took the degree of Bachelor of Arts, and that of Master, in 1740. In the interval between the two last mentioned periods, he was ordained, and by the interest of his uncle, Dr. Jaques Sterne, Prebendary of Durham, obtained the living of Sutton near York; the income arising from this could not have been very considerable, as his wife, to whom he was about this time first introduced, long resisted his solicitations to unite herself to him on the ground of the inadequacy of even their united means. In 1741, however, they were married, shortly after her recovery from a severe illness, during which she had given a most striking proof of her affectionate regard for him, having, at a time when she believed her recovery hopeless, left to him by her will, the entire of the fortune at her disposal. About this time, his uncle, with whom he yet continued on good terms, got him a prebendal stall in York cathedral, but soon after, "he quarrelled with him, and from that period became his bitterest enemy, because, (according as Sterne tells the story,) I would not write paragraphs in the newspapers, for though he was a party-man, I was not, and detested such dirty work, thinking it beneath me." Shortly after, he obtained by his wife's interest, the living of Stillington; and from that time for nearly twenty years, he continued to do duty there, and at Sutton, residing at the latter place. During the greater part of this period, his publications seem to have been confined to a Sermon for the charity schools in York, in 1747, and another preached before the Judges of Assize, in 1756.

In 1759, appeared the two first volumes of his Tristram Shandy, which speedily excited so much attention, and had such a rapid sale, that the following year, having taken a housee in York for his wife and daughter, he went up to London for the purpose of publishing a second edition. Of this singular book it is impossible justly to pronounce any general, decided, or summary opinion either in its favour, or the contrary; there certainly are many parts of it which possess great beauty and elegance, others contain the most piquant strokes of wit and humour, and at the same time evince a thorough knowledge of character; some of the episodes are exquisitely touching, and indicate a mind full of the finest sensibility; but it abounds with passages containing such gross and indelicate allusions as are utterly indefensible, and appear to have met with most deserved reprehension immediately on the appearance of the first volumes of the work. Yet Sterne, though fully apprized of this, seems to have totally disregarded every consideration but that of sordid profit; in one of his letters from London, he says, "one half the town abuse my book as bitterly as the other half cry it up to the skies--the best is, they abuse and buy it, and at such a rate, that we are going on with a second edition as fast as possible." Indeed on one occasion, when he was plainly told, that "his work could not be put into the hands of any woman of character," his only defence was a miserable attempt at ribald and indecent jocularity, coupled with an admission, that he wrote "to make his labour of advantage to himself." Tristram Shandy can in truth only be characterised as the most extraordinary melange of intelligent and reflective observation of human nature, and of the most profound absurdity, of highly wrought feeling, and of the most unmeaning and vicious frivolity that ever was or it is to be hoped, ever will be presented to the world.

It has been repeatedly said, and some treatises have been written to prove not only that Sterne was in a great measure a copyist of the manner of Rabelais, Montaigne, Bishop Hall, and some other old writers, whose works are but little read, but that whole passages in his Tristram Shandy, and Sentimental Journey could be pointed out, which, with very little alteration, are transcribed from Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy, and other works of a remoter period. There certainly were arguments brought forward almost amounting to proofs of this, yet even if we admit them to their fullest extent, enough of what is purely his own, will be found in Sterne's works to entitle him to the name of an original writer.

In the commencement of 1761, he was presented by Lord Fauconberg with the curacy of Coxwould, which produced some increase to his income, but obliged him to keep a curate for the parishes of Sutton and Stillington. He now came to reside at Coxwould, which he calls "a sweet retirement in comparison of Sutton." Here too, he draws a charming picture of the domestic occupations of his family:--" I am scribbling away at my Tristram; my Lydia helps to copy for me--and my wife knits and listens as I read her my chapters."

His health about this time, appears to have been very precarious; he had burst a blood-vessel in his lungs, and was otherwise so delicate, that he was advised to try the South of France, and from the Archbishop of York, he, without difficulty, obtained permission to be absent for a year or two. That he was an improvident man, and notwithstanding the income of his several church preferments, frequently much in want of money, is a circumstance pretty well known, and a tolerable sample of this is exhibited in the following letter which he wrote to Garrick, shortly before he set out for the Continent, the autograph of which is preserved in the collection of Mr. Upcott of London.

"Dear Garrick,

"Upon reviewing my finances this morning, with,

some unforeseen expences, I find I should set out with

20 pounds less, than a prudent man ought--will you lend

me twenty pounds.

"Your's

"L. STERNE."

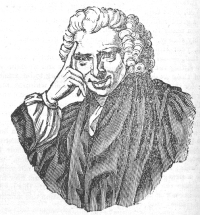

He would have the world to believe, that while at Paris, where he

arrived in January, 1762, he was courted and his society sought in the

most flattering manner, by all the men of rank, as well as of wit and

learning there, by the Duke of Orleans, (who, he says, got him to sit

for a portrait for him,) the Count de Choiseul, Baron d'Holbach,

Crebillon, and many others. Although it has been very generally said,

that his treatment of his wife through life, was unkind in the extreme,

yet this is by no means indicated by several letters which he wrote to

her from Paris, pressing her to come over to him with his daughter, and

to accompany him in his tour to the South. His journey thither was

hastened, in consequence of his having been nearly carried off by again

breaking a bloodvessel internally, just before the arrival of his wife

and daughter, in July. Accordingly, about the end of that month, they

set out for Toulouse, where they took a house for a year. The winter

was passed by Sterne, very agreeably in the society of some English

families, who were resident there, and who found in him a valuable

auxiliary in getting up some private plays at Christmas. About the

month of June following, he began to grow tired of Toulouse, and he

removed to Montpelier, and took up his residence there during the

winter of 1763. Early in the following year, though not much improved

in health, he determined on returning home, but his wife preferred

remaining after him in France. Some people were so ingenious as to

represent this, even at the time, as a "separation for life," but there

does not appear to have been any grounds for such a supposition,

especially, as they were again together at Tours, in 1706, and as in

1767, she rejoined him in England. An accusation of his having supplied

her most scantily with money seems to be equally unfounded. About June,

1764, he returned to England, where he was for some time chiefly

engaged in the printing of the concluding volumes of Tristram Shandy,

and the publication by subscription of two volumes of Sermons. About

this time, probably, he sat to Sir Joshua Reynolds for the portrait of

which we here give an engraving. His health again beginning to fail,

he hastened to Italy in the latter end of 1765, and spent the winter at

Naples. In his journey thither, through France, he does not appear to

have gone to see his wife or daughter, although they were then living

at Tours; yet his letters to them from Italy, do not show any

alienation, or even unusual coldness, and on his return, in the May

following, he paid them a short visit. His health after he got back to

England, began rapidly to sink, and we find him for some time at

Scarborough, trying the efficacy of the waters there. In 1767, he came

up to London to publish his Sentimental Journey, and while there, had a

violent return of his old complaint which proved very nearly fatal.

From this attack, he never perfectly recovered. His wife and daughter

returned from the Continent in the month of October, and settled in

York, and the society of his daughter, to whom he was much attached,

seemed to give him new vigour for a while, but his disorders as too

firmly rooted in his constitution, now enfeebled by repeated attacks,

and on the 18th of March, 1768, after a short but severe struggle, he

died at his lodgings in Bond-street, and was interred in the new

burying-ground belonging to the parish of St George's, Hanover-square.

He would have the world to believe, that while at Paris, where he

arrived in January, 1762, he was courted and his society sought in the

most flattering manner, by all the men of rank, as well as of wit and

learning there, by the Duke of Orleans, (who, he says, got him to sit

for a portrait for him,) the Count de Choiseul, Baron d'Holbach,

Crebillon, and many others. Although it has been very generally said,

that his treatment of his wife through life, was unkind in the extreme,

yet this is by no means indicated by several letters which he wrote to

her from Paris, pressing her to come over to him with his daughter, and

to accompany him in his tour to the South. His journey thither was

hastened, in consequence of his having been nearly carried off by again

breaking a bloodvessel internally, just before the arrival of his wife

and daughter, in July. Accordingly, about the end of that month, they

set out for Toulouse, where they took a house for a year. The winter

was passed by Sterne, very agreeably in the society of some English

families, who were resident there, and who found in him a valuable

auxiliary in getting up some private plays at Christmas. About the

month of June following, he began to grow tired of Toulouse, and he

removed to Montpelier, and took up his residence there during the

winter of 1763. Early in the following year, though not much improved

in health, he determined on returning home, but his wife preferred

remaining after him in France. Some people were so ingenious as to

represent this, even at the time, as a "separation for life," but there

does not appear to have been any grounds for such a supposition,

especially, as they were again together at Tours, in 1706, and as in

1767, she rejoined him in England. An accusation of his having supplied

her most scantily with money seems to be equally unfounded. About June,

1764, he returned to England, where he was for some time chiefly

engaged in the printing of the concluding volumes of Tristram Shandy,

and the publication by subscription of two volumes of Sermons. About

this time, probably, he sat to Sir Joshua Reynolds for the portrait of

which we here give an engraving. His health again beginning to fail,

he hastened to Italy in the latter end of 1765, and spent the winter at

Naples. In his journey thither, through France, he does not appear to

have gone to see his wife or daughter, although they were then living

at Tours; yet his letters to them from Italy, do not show any

alienation, or even unusual coldness, and on his return, in the May

following, he paid them a short visit. His health after he got back to

England, began rapidly to sink, and we find him for some time at

Scarborough, trying the efficacy of the waters there. In 1767, he came

up to London to publish his Sentimental Journey, and while there, had a

violent return of his old complaint which proved very nearly fatal.

From this attack, he never perfectly recovered. His wife and daughter

returned from the Continent in the month of October, and settled in

York, and the society of his daughter, to whom he was much attached,

seemed to give him new vigour for a while, but his disorders as too

firmly rooted in his constitution, now enfeebled by repeated attacks,

and on the 18th of March, 1768, after a short but severe struggle, he

died at his lodgings in Bond-street, and was interred in the new

burying-ground belonging to the parish of St George's, Hanover-square.

Of Sterne's general character, enough may be gathered from the preceding sketch to enable one to judge that his standard of morality was not very high. Many passages in his writings, would, no doubt, tend to the conclusion that he was of a most benevolent turn of mind, and had a heart very susceptible of compassionate feeling; yet it seems to be the universal opinion, that the whole tenor of his life went directly to contradict all this. His correspondence with Eliza (Mrs. Draper) seems to tell nothing to his advantage, or her's, though she seems to have been a woman of strict virtue. But no defence can be attempted for a clergyman, writing letters of the kind, to a married woman for the purpose of establishing what has been amiably termed, a Platonic affection! a phrase manifestly but a cloak for a criminal passion. Walpole has given us his opinion with a harshness which we fear is but too justly called for. (Walpoliana, 95.) His friend Garrick has taken him in the best point of view, in the epitaph which he wrote for his tomb.

"Shall Pride a heap of

sculptured marble raise

Some worthless, unmourned, titled fool to praise:

And shall we not by one poor grave-stone learn

Where Genius, Wit, and Humour sleep with Sterne?"

O'G.