On a New Mode of Saving Turf or Peat Fuel (from Irish bogs)

From The Dublin Penny Journal, Volume 1, Number 38, March 16, 1833

What constitutes the great anxiety of the most anxious of all mortals, an Irish farmer? The saving and bringing home of his turf. And why is he the most anxious of men? Because he is the subject, and too often the victim, of the most uncertain of climates. And why is the saving of his fuel, his most peculiar care? Because the saving and securing of that fuel, is the most precarious of all his changeful employments; and because on the security of that fuel depend the comforts of his house, the conveniencies of his homestead, and the thrift of horses, cows, pigs, poultry, and every thing about him. It is therefore altogether necessary for the Irish farmer to provide for his bog work, and in that very season of the year when agriculture requires all his hands; and when the Scotch farmer, or the English farmer, who depend on coals, can look to their turnip husbandry and their weedings, &c. &c. the Irishman is in his bog; there all hands are employed--there he is himself; and let who will want farmer Pat, from the 1st of June to the 1st of August, the answer is, "he is gone to the bog." And yet after all, when he is there, with all his merry men, and women too, he may do little good. He may cut the turf, but he may not save it. A summer so cold and so wet may come on, that after all his footings and clampings, turf may, instead of drying, dissolve under incessant showers of rain; and I have seen frequently in the course of my life, not only the poor labourer, but the strong farmer and the snug gentleman, reduced to the utmost distress for want of sufficient fuel; this may occur, as I have seen it, on the very verge of the bog of Allen; but in the south of Ireland it is on these occasions peculiarly distressing. At all times fuel is difficult to procure in the greater part of the counties of Tipperary, Cork, and Limerick; and the poor in these districts are obliged to go many miles to obtain fuel in the best of seasons; but in such wet summers as I have alluded to, turf becomes almost unattainable, and the poor wretched inmate of a comfortless cabin, has been obliged to depend upon the boiling of his potatoes on the evanescent tire got up by the crackling of thorns; and what is worse, when he has come home at evening, with his garments thoroughly soaked with wet, he has been obliged to go to bed to attain warmth, and has had to rise in the morning to put on the undried clothes that he had taken off the preceding night.

Would not the person who introduced a better system of saving fuel, be a benefactor to his country? Whether or not I shall be able to do that, I am not so sure, for I know my countrymen are opposed to all that is new fangled, but having seen in a sensible, business-like, Scotch publication, an account of a method introduced with success there, I lay it before Irishmen; and, good countrymen, I beg to assure you that I have been in Scotland, and have seen Scotch bogs, and they are as like ours as two eggs, and I have seen Scotchmen cutting sleive turf, and making hand turf, and the process was exactly like ours, therefore for the life of me I cannot understand why what has succeeded in Scotland, should not do in Ireland. I confess I have often thought that the great bog fields of Ireland might be made, in due time, as useful as the great coal fields of England and Scotland, and the present simple modification of machinery may be but the commencement of mechanical application, which may make the bog of Allen the most valuable property in the kingdom. Perhaps by the last remark I may exhibit my cloven foot as a detected speculator; but at all events hear the sensible Scotchman, a Mr. Slight, who in the transactions of the Highland Society, writes as follows:

"It has been shown above, that peat-moss, subjected to a moderate degree of pressure, becomes a fuel which, taken weight for weight, is capable of affording light and heat equal to the best common Scotch coal; and it also appears that the duration is nearly equal. The experiments do not seem to have extended to a comparison with peats dried in the usual way, but there can be no doubt that the superior density of compressed peat, especially when submitted to the composition process, will render it more available than the common peat to all useful purposes. As the expense of preparing by this process appears not to exceed that by the ordinary method, we have a quantity of light and heat, two most essential elements in the comfort of northern climates, at a price not exceeding one-fifth part of that obtained from coal, taking both commodities at first cost; while at the same time an incalculable advantage arises to the home consumer by the saving of time in drying his peats. All persons acquainted with the economy of the peat districts of Scotland, are aware of the inconvenience to which the poorer classes are subjected, by the occurrence of a wet summer, as it prevents the successful preparation of their winter fuel. Peats after being cut, must lie on the moor from one to two months, in the ordinary manner of drying, and in wet seasons even beyond that period, before they are fit for stacking. Even after all this, it sometimes happens that they are carried home in such a state of dampness, as to form a continual source of disappointment throughout the succeeding winter. To obviate this serious evil attendant upon cold and moist climates, let the new process be introduced, and the cottager not only gets free of the risk attending the preparation of his fuel, but he has the advantage of a superior article in his domestic comfort. It is presumed that by adopting a compressing machine, a period from eight to twelve days may be sufficient to produce the degree of dryness required. The introduction of a simple and efficient machine would therefore appear to be of great benefit to the inhabitants of the peat districts, and should the plan be objected to as expensive beyond the means of the poorer class, it may be answered that there is no necessity for each family or householder possessing one. Let the proprietor or tacksman furnish one or more for the use of his tenants or cottars, who might again pay a small equivalent for the use of the machine. As the cottars of one farm or one hamlet usually dig their peats in the same field, a sufficient number could join together to work it to advantage. For such situations the machine must be of the simplest construction, so as to be cheap, and little liable to derangement. The form which Mr. Tod has employed in his experiments, seems to fulfil these conditions. Its simplicity is such that the rudest mechanic may make it and keep it in repair. The first cost must be trifling, being little more than the prime cost of two or three rough planks. Perhaps, under present circumstances, nothing better could be devised for the purpose of local supply.

"But the subject may be viewed on a more extended scale. Let us look around us at the extensive fields of peat-moss lying in various portions of our island, and bear in mind that these vegetable deposits are materials in the vast laboratory of nature, in an incipient stage towards a formation similar to that of our present coal fields. Although we are unable to imitate a process, in which ages are required, yet there is one circumstance in it, which is within our power: we can employ pressure. And though from the limited term of action in all human energies and human agencies, we may not produce perfect coal, yet a substitute may be obtained approaching still nearer to it than the common peat."

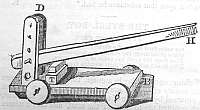

The following is the description of the machine.

"In constructing a machine for compressing peat, it seemed necessary that it should possess at least three distinct qualities --that it might be easily moved about, to prevent the peats having to be carried any distance--that it should have considerable power--and that it should produce its full effect with the least loss of time possible.

"To effect these objects, a machine was constructed, consisting of two strong planks of wood fixed together at each end by cross bars, and mounted upon four wheels.

"Two pieces of wood, CD, at the distance of 2 inches from one another, are mortised in the plank AB, at the end A, and at right angles to AB. Between the upright posts CD, there is inserted a strong beam AH, 12 feet long, and secured with an iron bolt passing through the pieces CD, which have numerous holes to admit of raising and depressing the beam AH at pleasure.

"Two boxes were then made, one of wood, and one of sheet iron: the wood-box being about 12 inches long, 4 inches in breadth, and 4 inches deep; the one of sheet-iron 14 inches in length, 3 1/2 broad, and 3 1/2 deep. The boxes had lids which just fitted them, about 3 inches in thickness, to allow them to sink in the boxes by the pressure.

"Each box was alternately filled with peat newly dug, the lid adjusted, and the box placed in the machine at the point T; a man stood at the end H of the beam AH, and as each box was placed in the machine at the point T, he bent his whole strength and weight upon the end of the beam. By this means, an immense pressure was applied to the box by a single effort, and in an instant of time, Two women filled and removed the boxes.

"In this way, a man and three women could compress about eight cart-loads in a day. One man digging, and a woman throwing out the peats, could keep this process in full operation.

"The peats when taken from the machine are built like small stacks of bricks, but so open as to admit a free circulation of air. The stacks put up in this way became perfectly dry, without being moved till they were led home.

"If the machine just described were to be adopted for compressing peat, boxes of cast-iron, full of small holes, would answer the purpose best. For the pressure was so great, that the wood box frequently gave way, though strongly made, and secured with iron at the ends; even the one of strong sheet-iron bent under the pressure."

The writer now goes on to compare a certain quantity of this peat or turf compressed by the machine, with Scotch coal, and he found that the peat, more especially that which is compressed from bog mud, gave out more heat than the coal. He then as follows, speaks of the comparative expense of saving fuel in the old, and that saved by the compression way. And here it is well to bear in mind, that four times the quantity of turf, in the compression way, can be saved on the same space of ground as what is saved in the common way.

"It has been already stated, that two men and four women could compress about eight cart-loads in a day. The wages for men this year at that season was 20d., and for women l0d. per day. But in order to make every reasonable allowance, let each man have 2s., and each woman 1s. per day, which would make each cart-load of compressed peats cost one shilling. Now in this part of the country, where peats are let by the cart-load, to be dug and dried in the usual manner, the general price is from 1s. to 1s. 3d. per cart load. But a great part of this expense is incurred in drying the peats after they are dug; for, by the common method, the peats are first spread upon the ground, and then put upon their ends in what are called Fittings--then put up in stacks of various dimensions, till they are become perfectly dry, and fit for being led home; and were it not for that additional labour, the peats could be dug and spread upon the ground in the usual manner, at one half of the expense incurred in compressing them.

"But then, it must be remarked, that compressed peats can be rendered perfectly dry, with equal saving of this additional labour, so that upon a fair estimate of the expense of the two methods of converting peat into fuel--that of compression would not much exceed that in common use; so that compression, in converting peat into fuel, will be productive of great advantages to those districts of the country that are dependent upon that substance for fuel."

Y.