Ruins of Mellifont Abbey, County of Louth

Ruins of Mellifont, County Louth

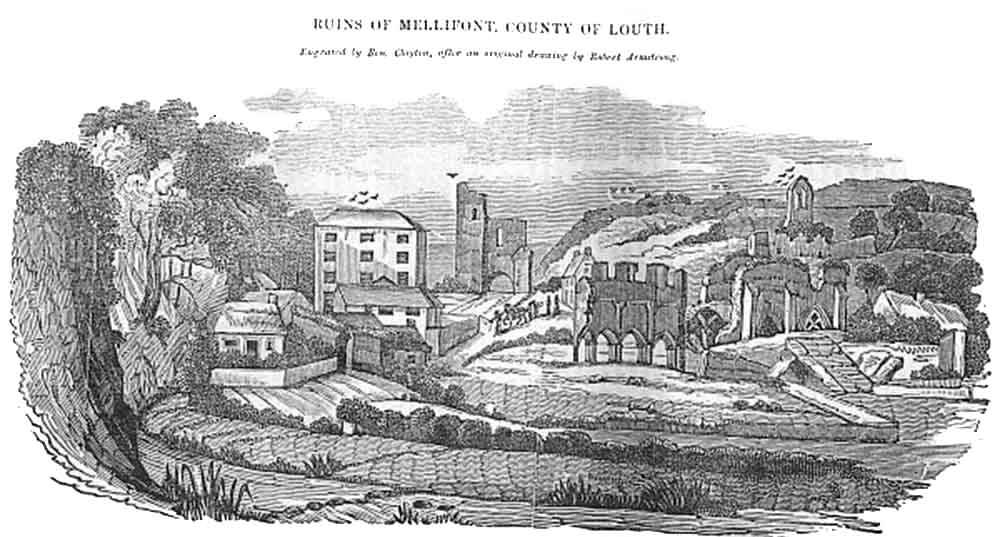

In this general view of the ruins of Mellifont, it is necessary to explain to the reader, that the large building to the left, with its adjoining offices, represents a modern Mill, the tower to the right, immediately over the figures, is the ancient Abbey gateway, the ruined buildings in front are the Baptistery and Chapel of St Bernard, and on the eminence, immediately above the latter, is seen the old parish church with its belfrey.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE DUBLIN PENNY JOURNAL

SIR,—Born in the immediate vicinity of Mellifont Abbey, and accustomed from my earliest youth occasionally to wander amongst its venerable ruins, I have been much gratified by observing in your twenty second number, your very succinct notice of these interesting remains, and having had a good opportunity of collecting a few notices and traditions concerning them, I take the liberty of submitting them to you.

A talented, though anonymous writer in a periodical, published some years since in this city, has observed that “notwithstanding the ridicule so frequently attached to the pursuits of the antiquary, and which, we must acknowledge, the airy dreams and idle speculations of many may seem to warrant, yet it will readily be admitted that researches of this nature, when guided by the true spirit of inquiry, become the sources of not only much pleasure but also of lasting advantage.

“The feelings arising from the contemplation of places which have been hallowed as the seats of religion and virtue, or celebrated as the residence of grandeur or of power, are nearly allied to the finest of the human heart: when we see those towers over which the banner of feudal greatness, once proudly floated, prostrate, or bending beneath the weight of ages, and now only crowned by the tangled ivy or noisome weed, nourished amid their decomposition and decay; when we wander through those halls which once echoed to the voice of revelry, but now only answer to the moaning of the wind or melancholy croaking of the raven; the heart must become better by the comparison, and we return to the world chastened, but corrected by the faithful picture.

“But these feelings are excited with far more energy and force, by a view of the remains of those religious edifices with which the piety of our ancestors has so plentifully furnished our island; to these sanctuaries do we owe the defence and preservation of our historical records, and of that learning which in the darkness of the ages, succeeding the overthrow of the Roman Empire, shed a short lived illumination over our western horizon, when the rest of Europe was involved in anarchy and confusion. Here, too, we find ourselves at every step, treading on the ashes of thousands of our fellow mortals, and from viewing the ruins of the works of man, the mind is irresistibly led to consider the weakness and transitory existence of man himself.”

It would be difficult to find a place more calculated to excite those feelings and reflections, than Mellifont Abbey, a spot which once could boast of saints for its inmates, princes for its votaries, and kings for its protectors; revered and cherished for ages, as a “fountain of honey”[1] from whence the refreshing streams of Christianity were distributed to many a sterile land, and a haven of rest, where many a weary pilgrim after the turmoil and tumult of a distracted life, sought, and found peace and happiness; and although the dissolution despoiled it of much of its former glory and importance, yet here formally years the proud barons of Mellifont held sway, and lorded it over the surrounding country; but now, lonely, degraded and desolate, the venerable ruins only stand, a perishing, though striking memorial of the fallen pride of man, and an evidence of the instability and uncertainty of his most sanguine worldly hopes and expectations.

After the account already given of the founding and consecration of this abbey, it is unnecessary to repeat these matters further than to say that Sir James Ware in his antiquities of Ireland, calls it the famous abbey of Mellifont, and states that in his time it contained many monuments, of which the most remarkable were those of Donogh the founder, and of Lucas de Netterville, Archbishop of Armagh; but of these tombs there are not now the slightest remains, nor can it be ascertained where they were situated, and we also learn from Fynes Moryson’s account of the war with the celebrated Onial, Earl of Tyrone, in the reign of Elizabeth, A. D. 1602, that Mountjoy, the then Lord Deputy, receiving private intelligence of the Queen’s dangerous illness, and wishing to bring matters to a speedy issue, dispatched Sir William Godolphin and Sir Garrett Moore, (whom he appointed commissioners) to Onial with a protection for his safe conduct, dated Tredagh, (Drogheda) 24th March, 1602-3.

On the 27th, Sir Garrett Moore rode to Tulloghoge, and conversed with Onial, and on the 29th Sir William Godolphin showed him the Lord Deputy’s safe guard, relying on which Tyrone on the 30th surrendered himself at Mellifont, on his knees to Mountjoy, and on the succeeding day made his submission in writing in the presence of a large assembly.

Mellifont Abbey lies about five miles N. W. from Drogheda on the verge of the county of Louth, the river Mattock, which flows through the ravine or valley in which it is situated, forming the boundary between that county and Meath.

The ruins are not remarkable for magnitude, but the minuteness and beauty of their details can scarcely be exceeded. They cover a considerable extent of ground, but from the effects of time, alterations and ruthless and unsparing plunder, it is now almost impossible to connect them so as to form a perfect whole.

In visiting this place from Drogheda, you proceed by Tullyallen, and after passing that village and the new church and glebe house of Mellifont, in the rere of Townly Hall demesne, you turn from the direct road to the right, and toiling for a mile over a bleak and sterile hill, on arriving at the summit you perceive in a deep hollow on your left, the upper parts of a few scattered ruins, and the roof of a modern mill; on the right, the view extends over the commons of Mellifont, to the pillar-like round tower, and ruined chapels of Monasterboice, famed for its antique stone crosses, while in front the prospect is bounded by the hill of Slane, crowned by its lofty abbey tower, embosomed in wood;—and the plantations and improvements of the late Lord Oriell, better known as speaker Forster, covering and ornamenting the hills of Collon.

Within two miles at the Boyne, (into which the Mattock flows) is the remarkable cave of New Grange; and the Druidic monuments, and Danish tumuli and encampments of Dowth; what a field for an Irish antiquarian!

Descending the hill, you arrive by a deflexion of the road at the river Mattock, which here enters a remarkable cleft or chasm. The eastern or Louth side is composed of limestone rock, rude and rough, thinly covered with a scanty turf, but, in many places entirely exposed; the bank, on the western or Meath side, rises nearly perpendicular from the margin of the stream to about thirty feet high, and is composed of clay.

A short distance down this valley a projection of the naked rock, approaches to within a few yards of the river, and here, the gate tower was erected of which you have given a sketch. This tower was square, and connected with the rock by a curtain or wall, entirely closing up the entrance to the area within, except by the low arched gateway; this wall is now removed, and the mill race is conducted under the archway.

On arriving at this gate tower, and not before, you have a perfect view of the area occupied by the abbey and its dependancies.

Immediately opposite, you perceive the octagonal building called the baptistery, and the entrance to the dungeon vaults; on the left, is the chapel of Saint Bernard, and near the summit of the hill a burial ground, with the ruins of a small church of modern date compared to the abbey, and probably erected since the dissolution. The right of the area is occupied by a large modern mill and offices, with various remains of the monastic edifices, and in the distance down the valley, the earth is literally strewed with fragments of walls and foundations, of which it is impossible at present to form any definite opinion.

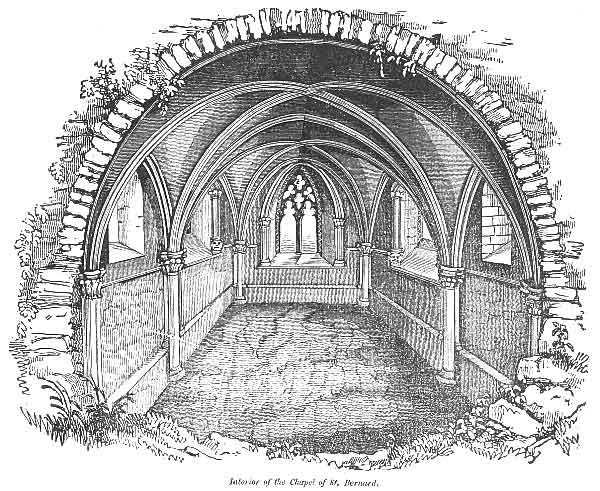

The first in order of these remains from the entrance tower is the chapel of St. Bernard, in which, it is probable, stood formerly, the tomb of Donough the founder. It is partly imbedded in the rock, the floor being considerably lower than the outer surface, and consists of a crypt or under ground Chapel, and an upper apartment.

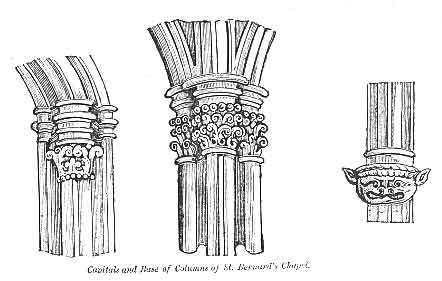

The crypt is a chaste specimen of the most elaborate and finished workmanship; the roof is groined, the arches springing from the clustered demicolumns on each side, exactly similar in design to the pillars in the Castle Chapel, but on a much smaller scale;—the capitals are all richly carved, with rich designs of foliage.

There are three windows and two arched recesses, the windows are also groined and pillared at the angles, the bases of the pillars representing grotesque heads, apparently pressed flat by the superincumbent weight.

The mullions are all destroyed, but some portions of the tracery of the tops remain, and a handsome lozenge or nail-headed moulding is continued round the interior of each.

A projecting basement runs round the interior of the chapel, about a foot high, and eight inches broad, the bases of the centre member of each column descend to the floor, but those of the parallel members only descend to and rest upon this basement.

In your 19th number you have given a sketch of the entrance door way;—I have never seen it, but it appears to have been worthy of the interior.

The upper apartment possesses no particular interest, being plain and devoid of ornament, and having a chimney and recessed closet, was evidently intended as a residence.

This beautiful specimen of ancient Irish art, was converted by the Moore family into a banquetting room, and having once echoed to the voices of the monks, hymning their matins, next resounded with the orgies of Bacchanals, but—now only answers to the noise of swine, being when last visited by the writer, occupied as a pigsty!!

“Sic transit gloria mundi.”

A little to the right of this is a small arch penetrating under the hill, said to be the entrance of a subterranean communication with Monasterboice, but this is scarcely possible.

The next object claiming our attention is the baptistery. This building has been an octagon, only four sides of which remain at present; each side was perforated by an arched doorway, and the exterior angles were ornamented by a reeded pilaster; a projecting cornice is continued round at half the elevation.

The doorways are arched and pillared, the arches are semicircular or Saxon, and together with the pillars are a perfect model of exquisite workmanship; they appear as if actually moulded in stone, not cut, and although they are uniform in their general appearance, no two are exactly alike in their details; and certainly, if the productions of a native artist, are highly valuable as a specimen of the state of the fine arts in Ireland, prior to the English invasion. The ornamental parts are composed of a red granite, and were formerly painted and partly gilt.

The roof of this building is gone, but the corbells of the groins are still attached to the walls inside.

Within a few feet of this temple, on the left are the vaults or dungeons, horribly dark and dismal; they are two in number, have one small aperture in each for the admission of light, and small recesses in the walls, apparently for holding the bread and water of affliction, doled out to the unhappy inmates. Here, it is probable, Dervorghil, the wife of O’Rourke, who may justly be considered the Helen of Ireland, closed her eventful life—in mortification and repentance, as we find she died and was buried at Mellifont, A.D. 1193.

Over these vaults, and scattered around, are several massive fragments of masonry, evidently thrown down by violence; and a little removed is a well, an inscription over which informs us, that our Lady’s well, after being lost for many years, was re-discovered and re-opened by the undersigned in the year 1826.

Beyond this and removed to the left, are the foundations of a large quadrangular building, of which I have not been able to ascertain the original intention.

Nestling among the ruins, and apparently trusting for protection to its very solitude and desolation, are several humble cottages, inhabited by still humbler inmates, who still fondly cling to a spot, hallowed by the traditional recollections of seven hundred years, and dear to their hearts as identified with the ancient glories of Ireland.

The Abbey of Mellifont was possessed of considerable revenues in lands and tithes; it is traditionally said that the tithes of all the land to Athlone belonged to it, and that the monks were so numerous, that going on one occasion in procession to Drogheda, the abbot, who was at their head, perceiving on entering into that town that he had forgotten his missal on the high altar, gave the word to the next, and so passing it from one to the other, the last man in the procession brought it with him: it is certain that at the dissolution it contained one hundred and forty monks beside lay brothers and servitors.

At the dissolution it was granted to Sir Edward Moore, ancestor to the Marquess of Drogheda, and under him and his descendants, underwent many alterations and vicissitudes. Among other ornaments, were the statues of the twelve apostles in stone, and Sir Edward, or one of his immediate successors, conceiving they were as efficacious in a temporal as in a spiritual capacity, clothed them in scarlet, clapped muskets on their shoulders, and transforming them into British grenadiers, placed them to do duty in his hall; they occupied this station for some time, but are now gone “to the moles and to the bats.”

There is another tradition concerning Mellifont, which, although not immediately connected with the ruins, possesses a degree of interest that will perhaps atone for its insertion here.

About forty years since, a young man in the neighbourhood paid his addresses to a young woman, a farmer’s daughter, and, although his attentions were not approved of by her friends, yet she encouraged him to hope, and eventually promised to marry him. His circumstances not being the best, and believing he might trust to her fidelity, he was inclined to defer the ceremony until he could realize a competence or sufficient to make her comfortable; but Mary, being sought after by many, pressed by her parents to decide, and believing his delay arose from indifference, at length became dissatisfied, and told him she would wait no longer, but marry the first man would ask her. He, thinking her declaration arose from a sudden caprice, carelessly told her to do so; and they parted in anger.

The miller of Mellifont was a douse, warm, middle aged bachelor, boorish in his appearance, and sottish in his manners, but withal having the name of money and a comfortable situation in the mill, he was far from being an object of indifference to the parents of unmarried females. Having long regarded Mary with a wistful eye, and been often proposed for her acceptance by her friends, she now, while warm with indignation against James, for what she considered his falsehood, consented to marry him; and, requesting it might be done as soon as possible, no time was lost, every thing was prepared for the wedding, and before twenty-four hours she was his wife.

Among the guests invited, James was not forgotten; perhaps she wished to enjoy a sort of triumph over him, and prove she could marry without him. He attended, but was downcast and sorrowful, taking no part in the boisterous merriment so general at country weddings, and appearing to pay no attention to what was passing around him.

After the bride had retired for the night, her husband, the miller, having indulged rather freely, was carried up in a state of insensibility and laid beside her, and the lights being removed, she had full leisure to reflect on her hasty conduct and her rash treatment of James, who she now found possessed her heart, although her hand was another’s.

Ere long she perceived a figure seated near the bed’s foot, and eagerly asking, “who is that?” was answered by James, “it is me, Mary, don’t be alarmed.”

“Why, James,” said she, “this is very improper conduct; I am now the wife of another, and if my husband wakens, or any person sees you here, it will destroy me; you must leave that, or I will call the people in.”

“I can’t, Mary,” said he, “for my heart is breaking.”

She still insisted he should leave her, but still received no other answer than “Mary, I can’t, for my heart is breaking.”

At length he sank exhausted on the bed; Mary greatly alarmed called aloud, and the company coming in, found him dead on the bed’s foot, his heart having really broken.

All was now confusion, his body was conveyed to his residence a few fields distant, and his friends having in vain tried every method to restore him, he was laid out to be waked. The practice then was, to put the body “under board,” that is, on planks, laid on the under frame of a large table, over which a large sheet was placed, which, falling down over the ends and sides, entirely concealed the corpse; on the table, they placed candles, tobacco, pipes, &c.

He was waked for two days, and all the neighbourhood made poor Mary the object of their execration and reproach. She never left her apartment, but sat seemingly unconscious of every thing, and bewildered with anguish. However on the second night she was missed; she had left her house unperceived, and had gone, no one knew whither, and as she could not be found after the strictest search, it was supposed she had drowned herself in the river.

In the morning, preparations were made for burying James, but in proceeding to put his body into the coffin, they found unfortunate Mary dead beside him. She had stolen unperceived under the table, and having insinuated her arm under his head, and placed his arm round her neck, she had in that position bidden adieu to all her sorrows.

Little now remains to be told; they were buried in one grave in Mellifont Abbey, and although in life they were separated, in death they were not divided.

ROBERT ARMSTRONG.

Raheny, Jan. 1833.

The annexed wood-cut represents the interior of the beautiful little chapel of St. Bernard. It, as well as the other illustrations, is copied from a drawing by our ingenious contributor Mr. Armstrong, who, our readers will perceive, has changed his place of residence, and, we are happy to add, his occupation also. The journeyman Housepainter of Ranelagh is now transformed into the Parish Schoolmaster of Raheny—a situation humble indeed for a man of his abilities, but better suited to his habits, less laborious and more healthful.

Interior of the Chapel of St. Bernard, Mellifont Abbey

The view is taken from the ruined entrance archway, in which formerly stood that exquisitely beautiful doorway of pointed architecture, of which we have given an outline in our 19th number. This doorway has been long since sold or as some state, lost at cards by one of the lordly proprietors, and is no longer to be found. The architectural beauty of this little chapel, even in its present dilapidated state, is exceedingly great, and exhibits perhaps the earliest specimen of undoubted gothic or pointed architecture to be found in the British Isands. There can be little if any doubt of its having been erected by the Monks of Clairvaux sent to Mellifont by St. Bernard himself, and the building was probably the oratory and habitation of the Abbot.

In the annexed details, the reader will find examples of the style of ornament and execution of the capitals and bases of the columns, which are of extraordinary beauty of workmanship and design.

To make our account of Mellifont as perfect as in our power, we shall give in a future number a view of the Baptistery, a building quite unique of its kind, and remarkable for great architectural beauty.

P.

Notes

[1] The name is probably derived from Mellifons.