An Irish Sea-Queen: Some Incidents in the Career of Grainne O’Mailley

Hill of Howth

The early history of the peninsular Hill of Howth, which sentinels the northern entrance to the Bay of Dublin, and one of the most striking features of which we engrave, is nearly altogether dependant on the Bardic creations of enchantment and glamourie associated with the deeds of Fionn-mac-Cumhaill and the Fenians.

But there is a story in connection with the hill which from its singular and romantic character is especially note-worthy. We allude to the incident which occurred in the year 1593, which has identified the name of Grana Uille, or Grainne O'Mailley, commonly known as Grace O'Malley, with its history.

This famous sea-queen was the daughter of Dubhdara O'Mailley (O'Mailley of the Black Oak) lord of the Isles of Arran and the territory of Ui-na-haille, or O'Mailley's land, a district comprising the present baronies of Murresk and Borrishoole, county of Mayo, and who, according to tradition, for many years in addition to not a little smuggling added other speculations to his connection with the sea; in short, like Lambro, Haidee's parent, he was noted for his bold and successful practise as a marine attorney.

At his decease Grainne succeeded to the command of his piratic squadron, and soon surpassed his plunderings by the extent and magnitude of hers, the natives along the entire western coast trembling at her very name.

This life, however, did not not prevent her twice yielding to the influence of that sly toxopholitic deity who “rules the camp, the court, the grove,” and who for her spread his wings to the blasts that swept the dark and stern cliffs of Ui-na-haille.

Her first husband was Donnell O'Flaherty, a distinguished chief of the sept of that surname, who formerly possessed all Western Connaught, and whose character about this period may be recognised from the inscription which the terror-stricken burghers of Galway are said to have placed above the western gate of that city:

“From the ferocious O'Flaherties good Lord deliver us!”

After his death her second spouse was Sir Richard Bourke, head of the Mayo sept of that Norman-Irish clan, whom he governed under the title of “Mac William Eighter,” i.e. the lower, the Earl of Clanricarde being chief of the upper or senior sept.

Sir Richard died in 1583.

Grainne's piracies became so frequent and notorious, before and after her first marriage, that at length, in 1570, she was proclaimed as an outlaw, a reward of £500 was offered for her apprehension, and troops were sent from Galway to take the castle of Carrick-a-Uille, in the Bay of Newport, which was her chief stronghold, and her defence of which was so spirited that the beleaguers were compelled to ignominiously retreat, after a siege of more than a fortnight.

However, the extension of English influence in Connaught ultimately induced her to come to terms with the Government, and in the summer of the year 1593 she sailed for England, and obtained an interview with Queen Elizabeth at Westminster, to the astonishment of her majesty's farthingaled and ruffed dames d'honneur, who appear to have been considerably struck with the mien and appearance of this marine Amazon.

“As a book,

That sunburnt brow did fearless thoughts reveal;

And in her girdle was a skean of steel.

Her crimson mantle her gold brooch did bind;

Her flowing garments reached unto her heel;

Her hair, part fell in tresses unconfined,

And part a silver bodkin fastened up behind.”

The queen consented to pardon her transgressions upon a promise of future amendment, which Grainne rather reluctantly gave, and, after a short sojourn, returned to Ireland, debarking at a little creek near Howth Castle, to which she proceeded, but the gates of which, as it was customary at dinner time, she found closed.

Indignant at such a dereliction of national hospitality, she seized the infant heir to the title, who chanced to be rambling with his attendants along the beach, and conveyed him to the castle of Carrick-a-Uille, nor would she consent to restore him until she had exacted a heavy ransom, and an express stipulation that the gates of Howth Castle should never again be closed at dinner time, and that a cover should always be in readiness for any stranger that might arrive—a custom scrupulously observed through many generations.

Grainne reached a very advanced age, and at her death, which occurred early in the seventeenth century, was interred in the monastery of Clare Island, which she had endowed, and where some remains of her tomb are still visible.

Her celebrity was long the subject of bardic song, and yet forms the theme of ballads and the subject of legends among the peasantry.

There is a noble march called “Graine Mael, or Ma, Ma, Ma,” preserved in Bunting's “Ancient Music of Ireland,” the author and date of which, are uncertain, but it is probably as old as the corsairess herself.

When played on the pipes the time at intervals is denoted by a peculiar sound, which has procured for it the additional name of “Ma, Ma, Ma.”

During the political contests that marked the Duke of Dorset's administration of Ireland, in 1753, an air, partly Irish and partly English, founded on this melody, was very popular.

In the dining-hall of Howth Castle there is a painting which is locally believed to represent her abducting escapade. A lady mounted on a white steed is in the act of receiving an infant from a peasant: from an opening in the sky above a figure gazes downward on the group.

Where Grace obtained her white charger tradition does not say, but perhaps she had on board her fleet a division of that famous corps known as the “horse-marines.”

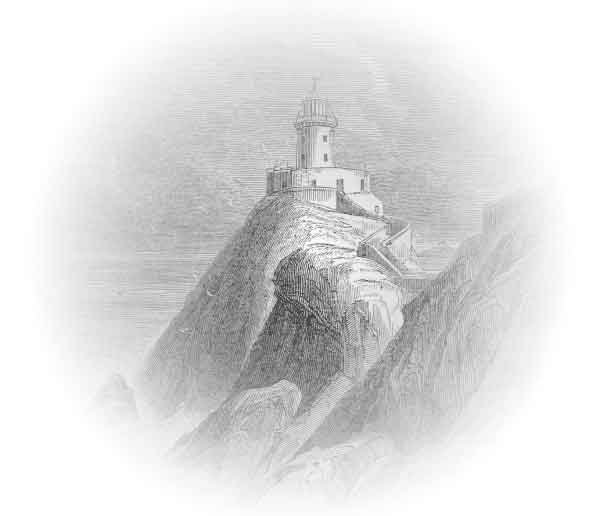

On the loftiest headland of Howth, at its extreme south, and by the marge of pleasant grassy slopes, stands the snowy Lighthouse of the Bailey. The historic recollections which crowd around the site of this picturesque pharos are of much interest. Contemporarily with the synarchy of Eremhon and Emhear in Ireland, in the year of the world 3501, a fortalice called “Dun Etar,” the Fort of Etar—or Fort of Howth, the ancient appellation of this locality being “Beann Etar,” that is Beann-o-tir, the hill from (or off) the land, an expressive allusion to its almost insulated position—was erected here by a chieftain named Suirge, as thus recorded in an ancient historical poem, preserved in the “Book of Ballymote,” descriptive of the nomadic adventures of the Milesians, and of the various palaces and fortresses constructed by them:—

“Dun Sobhairce was afterwards erected

By the gallant Sobhairce, of the fair side;

Deilg-inis, by Segda, the cheerful;

Dun Etar, by Suirge the slender.”

Duns Sobhairce and Deilg-inis were forts on Dunseverick, an isolated rock in the vicinity of the Giant's Causeway, county of Antrim, and Dalkey Island. Naturally impregnable at that time, on the extern or sea-side, the precipitous cliff the apex of which it encircled rendering any artificial protection unnecessary, while its intern defensibility was secured by a deep fosse, which completely cut it off from the hill, in addition to formidable lines of circumvallation, the fastness of Etar for centuries may be said to have formed the keystone of power on the peninsula, in the history of which it is a solid landmark, as it gave its name to many of the sanguinary conflicts that from time to time resulted for its possession, here, with their faces to the foe and their backs to the waves, being the final stand of its defenders after contesting the soil foot by foot.

In the ninth century of the Christian era the monarch Crimhthainn Niadhnair (pronounced Criffan Nianair) who succeeded to the sovereignty of Ireland, A.M. 5193, died at Dun Etar—which was from thenceforward distinguished as “Dun Crimhthainn”—in the sixteenth year of his reign, after his return from a predatory expedition, the scene of which is uncertain, in which he amassed considerable spoils.

King Crimhthainn, as we learn from the “Leabhar na h-Uidhe,” a work compiled at Clonmacnoise, in the twelfth century, and the “Dinnseanchus,” was interred in the royal cemetery of Brugh na Boinne, on the banks of the Boyne, the usual place of interment for princes of the Tuatha de Danann, and whose custom he adopted at the solicitation of Nair, his queen, who was of that mystic race, and from whom he derived his surname of Niadh-nair, “Nair's Hero,” otherwise attributed to a Bainlean-nán, or tutelary female sprite, who was fabled to have accompanied him on his expeditions.

The wreck of a carn which crowns the summit of Sliabh Martin, the loftiest pinnacle of Howth, has heretofore been popularly regarded as his sepulchral monument, a conclusion which, it will be manifest, is entirely erroneous.

In the early part of this era Conary the Great also had a royal fortress here, and made several expeditions thence into Britain and Gaul.

In the year 646—or, according to the “Annals of Ulster,” 649—a sanguinary engagement was fought here, known as the “Battle of Dun Crimhthainn,” between the monarchs Conall and Ceallach, the sons of Maelcobha, and Aenghus and Cathasach, sons of Domhnall, the sovereign who preceded them on the throne, in which the latter were slain.

In the early part of the eleventh century (1012), during the reign of Brian Borumha, Maelmordha, King of Leinster, with an auxiliary force of Danes, under Sitric, King of Dublin, invaded and devastated the fertile plains of Meath, to avenge which Malachy II., from whom Brian had usurped the supreme power, retaliated by an incursion into their territories, which he ravaged, burned, and razed as far as Howth, but was overtaken at Draighnen (Drinan, near Kinsaly,) and defeated with a severe loss, including his son, Flann.

Towards the close of the century, however, the Leinster troops sustained a retributive defeat from Muircertach Ua Brian, King of Munster, at “Rath Etar,” a stronghold which was probably identical with Dun Crimhthainn, in which fortalice, also, a remnant of the Danes who had escaped the slaughter at Clontarf, in 1014, are traditionally said to have fortified themselves, and defended with desperate resolution until relieved by a Norse fleet.

This is the last record we find of a fort which held so important a position in the annals of the past, and from the massive and compact strength of which the shocks of war and tempest once rebounded ineffectually.

It has long ago passed away and mingled with the dust, but many traces of the original fosse and circumvallation were clearly discernible a few years since. The superstructure reared in its stead—

“A new Prometheus chained upon the rock,

Still grasping in his hand the fire of Jove,”

not less element-defiant when the waves leap over it,

“And steadily against its solid form

Press the great shoulders of the hurricane,”

has another character and a nobler design.

The Bailey Lighthouse was erected by the Ballast Board of Ireland in the year 1813, in lieu of one of two built on Howth by Robert Readinge, in the reign of Charles II. (1671) which crowned an eminence more to the north, and the desuetude of which was occasioned by its great altitude—three hundred feet—which rendered it liable to be obscured by hanging mists.

The shape of the present structure is that of a truncated cone, the illumination, a clear fixed light, being produced by a set of parabolic reflectors, and visible in clear weather at a distance of fifteen nautical miles.

The parallels of defence which engirt the ancient Dun, were marked by two distinct divisions, a greater and a leaser, as apparent from an attentive examination of the existing outlines.

The source of the term Bailey has occasioned many conjectures, more or less fanciful.

It has, however, been generally traced to the Irish baile, a town, a very frequent topographical prefix, and said to be cognate with the Greek polis, and Latin ballium, which in their original sense implied an elevated circular fortification, afterwards extended to the villages of which such citadels were the nuclei.

But the authorities for the synonymity of baile, polis, and ballium, and their special application to hill fortalices and towns are very doubtful, and the correct radix of the word appears to be beal, beul, or bel, literally an entrance, pass, or mouth, as well as correlative to the Welsh beile, an outlet, mound, or bailey, from bal, a prominence, or what juts out.

The “Lighthouse of the Bailey,” therefore, simply means the lighthouse of the out-jutting rock or promontory.

This word beal, as also baile, a town, enters largely into Irish topology, as Beal-feirside, Belfast, “the pass of the sand-bank;” Beal-atha-na-sluagh, Ballinasloe, “the pass of the multitude,” Beal-an-atha, Ballina, “the pass of the ford,” etc.

During the night of the 15th of February 1853, in a severe snow storm, the Victoria steam-vessel, from Liverpool to Dublin, struck near the Castlena Rock, off the east side of Howth, from whence she drifted as far as the promontory of the Lighthouse, and being thence backed into deep water, went down within a few yards of the shore, a complete wreck, sixty persons, including the commander, Captain Church, perishing.

This sad event will recal to the reader that masterly description in Longfellow's beautiful ballad “The Wreck of the Hesperus,” which gives us a picture of a similar tragedy.

The breakers were right beneath her bows,

She drifted a dreary wreck

And a whooping billow swept the crew

Like icicles from her deck.

She struck where the white and fleecy waves

Looked soft as carded wool;

But the cruel rocks, they gored her side

Like the horns of an angry bull.

Her rattling shrouds, all sheathed in ice,

With the mast went by the board!

Like a vessel of glass, she stove and sank,

Ho! ho! the breakers roared!

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Such was the wreck of the Hesperus,

In the midnight and the snow!

Christ save us all from a death like this,

On the reef of Norman's Woe!

The scenery in the immediate vicinity of the Lighthouse is very attractive, and has tempted many a gipsy party, satiated, perchance, with the coup d'oeil around, or flushed and panting from their climb of the heather-draped and worn sides of the hill, to a grateful halt, and the earnest discussion of well-stored hampers, a matter-of-fact employment in such a place. And often will those sunny days, with their pleasant lessons of—

“How the best charms of nature improve,

When we see them reflected from looks that we love,”

be scanned by the way-weary pilgrim of life, as the thoughts fly back along the phantom years, and memory pictures through their dim haze forms that once breathed and moved-aspired and loved. Alas! that ever,

The bough must wither, and the bird depart,

And winter clasp the world-as life the heart!

E. M‘M.