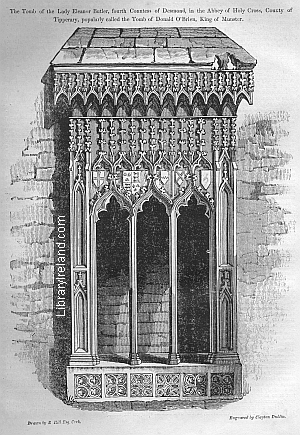

Tomb of Eleanor Butler, Countess of Desmond

From The Dublin Penny Journal, Volume 1, Number 42, April 13, 1833

It will possibly startle many of our readers, when we say that Ireland has never hitherto produced an antiquary, taking that appellation in its general and extensive signification. We have had useful and laborious historical compilers--antiquaries in our ancient literature--but in nothing else deserving the name. Even this appellation is scarcely merited by the majority of those compilers, who extract every thing that falls in their way, without the ability to judge of its value, or to discriminate between that which is true and that which is obviously disentitled to credit. To constitute an antiquary, even in a limited sense, something more is necessary than the mere ability to make extracts; and an antiquary, properly so called, in the more extensive meaning of the word, requires a combination of powers and acquirements, much greater than is generally supposed, and which rarely are found united in the one individual.

An antiquary should possess, not only an intimate acquaintance with the

history and literature of his own country, but also with those of every

other in any ways however remotely connected with it. He should have a

general if not critical knowledge of the progress of the various arts

of civilized man, and the changes that have taken place in them, as

exemplified in the architecture, sculpture, inscriptions, medals,

&c. &c. of all ages. He should have an accurate eye and

a cultivated taste,; and above all he should possess a vigorous and an

honest understanding, not to be swayed by visionary national

prejudices, but able to weigh evidences, and seeking truth above all

things. Without these qualifications, a man may spend a life in poring

over rare books or time-worn records, and be, nevertheless, but a

useful grub, or pioneer, for the antiquary or historian--without ever

meriting the honorable titles of antiquary or historian himself.

Ireland has produced some able literary antiquaries--of whom both

Ussher and Ware had each the learning, industry, and mental acuteness

necessary for a general antiquary; but the science of antiquities was

in its infancy, in Great Britain, in their times, and in Ireland they

had to plant the very seeds of antiquarian knowledge. Their labours

were, consequently, almost exclusively literary--the search after

hidden historic facts, and the amount of their discoveries, in this

hitherto unexplored field, were such as entitle them to the lasting

gratitude of their country. Since their time we have had some

industrious and praiseworthy compilers--as Harris, Lodge, Archdall, and

others, who by their compilations from unpublished MS. remains, have

added largely to our accessible stock of historic knowledge. But above

all the men of this class, we are most indebted to the late Dr.

O'Conor, whose translation of so large a portion of the ancient annals

of Ireland, and the great extent of learning and research exhibited in

the dissertations appended to them, entitle him to the highest praise

and honour, as a zealous and profound historical antiquary. In regard

to our ancient history and literature, therefore, much has been done of

a valuable character, and though much still remains hidden, the road

has been cleared of many of its obstructions, and the journey of future

explorers will be comparatively easy. But in every other department of

antiquarian science, the ancient pagan monuments, architecture, tombs,

crosses, ornaments, and everything that illustrates the progress and

extent of our forefathers' attainments in the arts of civilized

life--all these have been unillustrated, or illustrated in such a way

as only to involve them in additional obscurity, and to prove the utter

incompetency of those who have attempted to treat of them. Hence it has

happened that a real history of Ireland is still a desideratum, for the

historian can travel safely only in the wake of the antiquary; the past

state of a country cannot be accurately known till its antiquities have

been thoroughly and accurately investigated. It is hardly necessary for

us to disclaim the arrogant assumption for ourselves of such extensive

qualifications as we have stated to be necessary to constitute a true

antiquary. Our sole object is to show the learned of our countrymen

that a nearly unexplored field of inquiry is open to them, in which

pleasurable occupation and honour may be gained. In the meantime, we

shall endeavour, in our own humble way, to plant the seeds of

antiquarian investigation in our country, and venture to hope that our

little Journal may be the medium through which a clearer light will be

thrown on the ancient state of Ireland, and our antiquities be placed

on a more solid basis.

An antiquary should possess, not only an intimate acquaintance with the

history and literature of his own country, but also with those of every

other in any ways however remotely connected with it. He should have a

general if not critical knowledge of the progress of the various arts

of civilized man, and the changes that have taken place in them, as

exemplified in the architecture, sculpture, inscriptions, medals,

&c. &c. of all ages. He should have an accurate eye and

a cultivated taste,; and above all he should possess a vigorous and an

honest understanding, not to be swayed by visionary national

prejudices, but able to weigh evidences, and seeking truth above all

things. Without these qualifications, a man may spend a life in poring

over rare books or time-worn records, and be, nevertheless, but a

useful grub, or pioneer, for the antiquary or historian--without ever

meriting the honorable titles of antiquary or historian himself.

Ireland has produced some able literary antiquaries--of whom both

Ussher and Ware had each the learning, industry, and mental acuteness

necessary for a general antiquary; but the science of antiquities was

in its infancy, in Great Britain, in their times, and in Ireland they

had to plant the very seeds of antiquarian knowledge. Their labours

were, consequently, almost exclusively literary--the search after

hidden historic facts, and the amount of their discoveries, in this

hitherto unexplored field, were such as entitle them to the lasting

gratitude of their country. Since their time we have had some

industrious and praiseworthy compilers--as Harris, Lodge, Archdall, and

others, who by their compilations from unpublished MS. remains, have

added largely to our accessible stock of historic knowledge. But above

all the men of this class, we are most indebted to the late Dr.

O'Conor, whose translation of so large a portion of the ancient annals

of Ireland, and the great extent of learning and research exhibited in

the dissertations appended to them, entitle him to the highest praise

and honour, as a zealous and profound historical antiquary. In regard

to our ancient history and literature, therefore, much has been done of

a valuable character, and though much still remains hidden, the road

has been cleared of many of its obstructions, and the journey of future

explorers will be comparatively easy. But in every other department of

antiquarian science, the ancient pagan monuments, architecture, tombs,

crosses, ornaments, and everything that illustrates the progress and

extent of our forefathers' attainments in the arts of civilized

life--all these have been unillustrated, or illustrated in such a way

as only to involve them in additional obscurity, and to prove the utter

incompetency of those who have attempted to treat of them. Hence it has

happened that a real history of Ireland is still a desideratum, for the

historian can travel safely only in the wake of the antiquary; the past

state of a country cannot be accurately known till its antiquities have

been thoroughly and accurately investigated. It is hardly necessary for

us to disclaim the arrogant assumption for ourselves of such extensive

qualifications as we have stated to be necessary to constitute a true

antiquary. Our sole object is to show the learned of our countrymen

that a nearly unexplored field of inquiry is open to them, in which

pleasurable occupation and honour may be gained. In the meantime, we

shall endeavour, in our own humble way, to plant the seeds of

antiquarian investigation in our country, and venture to hope that our

little Journal may be the medium through which a clearer light will be

thrown on the ancient state of Ireland, and our antiquities be placed

on a more solid basis.

We have been led into those introductory remarks, on reading over the various erroneous notices which have been given of the subject of our prefixed illustration, which represents the finest specimen of tomb architecture which time and barbarism have allowed to remain in Ireland.

This interesting monument is situated on the south side of the choir of the Abbey Church of the Holy Cross, in the county of Tipperary; and is generally believed to be the monument of Donald More O'Brien, King of Limerick, the founder of that magnificent pile, in the year 1169. As our present object is solely to elucidate, if possible, the real owner and age of this tomb, reserving our history and description of the Abbey for a future number, we shall only, with reference to this date, remark, in the words of a skilful architectural antiquary, Dr. Milner, that the present ruins exhibit a style of architecture of a later period than Donald's reign, by more than a century.

No stronger evidence need be given of the non-existence of antiquarian knowledge in Ireland, hitherto, than the fact that the origin and age assigned to this tomb have never been questioned. Doctor O'Halloran, a visionary chronicler, was, we believe, the first who gave it the appellation of the mausoleum of Donald O'Brien. In his introduction to the study of the history and antiquities of Ireland, he gives, with others, a plate of it under the above appellation, as a monument erected before the arrival of the English, and as he says--"the most satisfactory reply to the assertions of Mr. Hume and others concerning the state of this kingdom before Henry the Second's reign." Among these architectural monuments, the mausoleum of Donald O'Brien, is put foremost, as of greatest importance, and lest the reader should entertain any doubt of the accuracy of the date assigned, either to this or the subjects of the succeeding plates, he adds--" whoever is acquainted with the works of Ussher, Ware, Harris, &c., can attest, that there is no imposition given in the account of each plate." Should the reader, however, refer to those author, he will find no account whatever of this tomb, nor of the abbey in which it exists, beyond the date of its first foundation; to which date, as we have already remarked, the present ruins cannot possibly be assigned. This assertion thus backed by veritable evidence, was deemed conclusive even by Campbell, Archdall, Ledwich, and the smaller tribe of compilers, who re-transcribe, without inquiry or doubt, every thing that falls in their way. And yet even the very slightest acquaintance with the architectural or monumental antiquities of Great Britain and Ireland, would have enabled any one to perceive that this tomb did not belong either to the person or the age assigned to it.

We cannot, however, claim the merit of being the first to discover this error. Sir Richard Colt Hoare, an English antiquary, though unacquainted with our national antiquities, could not avoid discovering an anachronism so obvious, and had no hesitation in expressing his scepticism. Speaking of this tomb, he says, "It has generally been attributed to Donogh Carbragh O'Brien, (recte Donald More) king of Limerick, who founded the abbey of Holy Cross, and who died about 1194. This illustrious personage," he adds in a note, "surnamed Donal More, or Donal the great, was proclaimed king of Munster in the year 1168; he died in 1194; but the place of his interment is not mentioned by Mr. Lodge in the account of the family of O'Brien. I am inclined to think that this tomb has been improperly attributed to him, as it does not bear in its architectural decorations the appearance of so old a date as 1194; neither do any of the bearings on the three escutcheons of arms, which are placed upon this monument bear any resemblance to those of the O'Brien family." He adds in the text, "I have since been informed by an able Irish antiquary, that it belongs to the O'Fagarty (Fogarty) family; this doubt might be cleared by examining the escutcheons of arms that are placed upon the tomb."

Let us now proceed to such examination; and we shall find how easily the questions of the origin and proprietorship of this monument can be settled.

There are five shields, four of which have armorial bearings, and the fifth is plain, or the bearings have been possibly obliterated.

The first, on the dexter side, or that opposite the left arm, bears a cross--St. George, the ancient arms of England, or perhaps with greater probability, the arms of the abbey, in allusion to its name.

The second,--the arms of England and France, quarterly, on a larger shield, as a mark of honourable distinction.

The third,--Or, a chief indented, azure, the arms of the noble house of Ormond.

The fourth,--Ermine, a saltier, gules,--the arms of the house of Desmond.

These armorial bearings demonstrate incontestably that neither of the ancient Irish families of O'Brien or O'Fogarty have any claims to the honour of the erection of the monument; and that it exclusively belongs to a person of the house of Desmond and Ormond. Referring, then, to the genealogical histories of those two noble families, we find that the first intermarriage which took place between them, was at the very period to which the style of architecture of this tomb unquestionably belongs, namely, the fourteenth century, when Gerald, the fourth earl, married in 1359, by the king's command, Eleanor, daughter of James, the second earl of Ormond, and by her, who died in 1392, had two sons, John and James, who succeeded successively to the title, and a daughter, Joan, the second wife of Maurice, the sixth baron of Kerry. The tomb must therefore belong to either of those persons; and we have now only to ascertain to which of them it should properly be referred.

That it was not erected for the earl, though he may possibly have been subsequently interred therein, will, we think, appear evident from the following circumstances:--

First, that he had no right to have the royal arms placed upon his monument, nor would the arms of his lady's family have been placed on the dexter side, but impaled with his own.

Secondly, it appears from the histories of the times, that the countess died in the year, 1392, and that he survived her to the year 1398. And

Lastly, it appears that the manner and time of his death were unknown to the English in Ireland, the histories of the family stating that in the year 1397, he went out of his camp near the island of Kerry, and was supposed to have been privately murdered, being never heard of more. And though it appears, as we shall presently show, from the Irish annals, that these opinions were erroneous, both as to the year and circumstances of his death, still such could hardly have prevailed, if a tomb of this striking grandeur had been erected to him a district then in the possession of the English. From the following entry in the Annals of the Four Masters, now first given to the public, it will be seen that he was not murdered, as supposed, in the year 1397, but died among the clergy in the following year.

"1398. Garrett, (Gerald) earl of Desmond, a cheerful polite man, who had excelled all the English of Ireland, and many of the Irish, in his knowledge of the Irish language, of poetry and history, and also in all the other literature of which he was possessed, died after the victory of penance." (Iar m-buaidh n-aithrighe.)

Thus, it is evident that though, as we have already said, the earl may have been interred in this monument--a circumstance not impossible--it could not have been expressly raised for him.

On the other hand, in assigning the erection of this tomb to the countess of Desmond, there are no difficulties whatever.

First, her own family arms are with propriety placed on the dexter side of the Desmonds, as being more honourable, her father, James, the second earl of Ormond, being the great grandson of king Edward I. and hence, as Lodge says, usually called the "noble earl," on account of his descent from the royal family. And this accounts also for the royal arms of England and France being placed on the dexter side of the Butlers.

These evidences are, we think, in themselves sufficient to settle this question--but they are corroborated by others. We learn from Archdall that "the tradition of the place informs us that this tomb was erected for the good woman, who brought the holy relic thither." And it appears from the notice of her death in the Annals of the Four Masters, that such a cognomen was quite applicable to the countess, who was equally remarkable for her generosity and piety.

"1392. The Countess of Desmond, daughter of the earl of Ormond, a bounteous and truly hospitable (or generous) woman, died after the victory of penance." (post palmam paenitentiae.)

We may, therefore, with historical certainty, assign this interesting monument to the good countess. But there is another fact of equal interest consequent upon this conclusion, viz. that considering its situation on the right of the high altar of the church, the place usually occupied by the tomb of a founder , and the perfect accordance in architectural style between this monument and the venerable abbey in which it is placed, it should, we think, hardly admit of a doubt, that this illustrious lady was also the rebuilder of the noble abbey church of the Holy Cross--a fact hitherto unknown to history.

P.