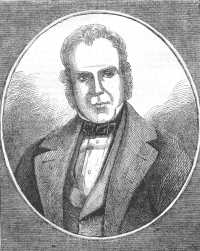

National Tintings II: William Carleton

From The Illustrated Dublin Journal, Volume 1, Number 9, November 2, 1861

WILLIAM CARLETON was born in

1796, in the townland of Prillisk, parish

of Clogher, and county of Tyrone. His father was a small farmer, with a

family of fourteen children, the subject of our present tinting being

the youngest. He was a simple peasant, his son tells us, of unaffected

piety and unblemished integrity. The extraordinary knowledge of the

customs traditions, and pastimes of the Irish, which enriches

Carleton's works, has been communicated to him by his father, while he

seems to be indebted to his mother for the more poetical attributes of

his genius.

WILLIAM CARLETON was born in

1796, in the townland of Prillisk, parish

of Clogher, and county of Tyrone. His father was a small farmer, with a

family of fourteen children, the subject of our present tinting being

the youngest. He was a simple peasant, his son tells us, of unaffected

piety and unblemished integrity. The extraordinary knowledge of the

customs traditions, and pastimes of the Irish, which enriches

Carleton's works, has been communicated to him by his father, while he

seems to be indebted to his mother for the more poetical attributes of

his genius.

From Prillisk the family removed to a place called Tonagh, where he commenced his education under the tutorage of a Connaughtman, named Pat Freyne; but up to his fourteenth year his studies were of a very desultory nature, owing to the erratic habits of those hedge-school teachers, upon whom the peasant children were altogether dependent for educational knowledge in those days. He was placed under several of those country pedagogues and tyrants, among which latter was a classical teacher at Tulnavert, whose name he has refrained from giving, but who figures at full length in one of his most beautiful and popular tales, "The Poor Scholar."

Although possessed of a mind capable of imbibing knowledge rapidly, he made but little progress under those men in his education. We believe book lore to have been the least of it; but the life-pictures he has given us of this class of persons in his works, prove that his attendance upon them was not altogether purposeless, for even at that early period of life he was unconsciously noting those phases of character which they presented.

Notwithstanding that he possessed those powers of observation, he was, in his boyhood, more remarkable for simplicity of mind than precocity of intellect; in exemplification of this, we shall relate an anecdote that is told of him.

He once undertook to deliver a letter from a Catholic clergyman to a physician who lived some twelve miles distant from his residence. He proceeded on his way and returned in due time, or a little before it.

"Why, William, you've got back soon," said his cousin for whom he had performed the journey, as he saw him return. "Yes," replied young Carleton, "but I didn't go the entire way, for I forgot the name of the gentleman to whom I was going, and had to come back to inquire."

"And where had you the letter?" asked the other.

"I had it here in my pocket," he replied, drawing it out.

His companion took it from him, and turning up the direction, handed it back--"Wouldn't it have been better for you to have looked at that, and have saved yourself the trouble of coining such a journey?' he asked. We may imagine the blankness of the lad's face on discovering his blunder, which, we need hardly add, was for many a day made the subject of raillery among his schoolfellows whenever it was mentioned.

When he had reached his twelfth year, his parents, who designed him for the church, and who were, therefore, anxious as to his progress in learning, resolved upon sending him to Munster, to complete his education as there was no classical school within eighteen or twenty miles of Springtown, where they then resided. Accordingly, his simple outfit was prepared, the funds necessary to defray his expenses being supplied by his parents; but their scanty means would not permit of their adding to this sum as much as might enable him to travel in the ordinary way; so he was to trust to the hospitality of the peasantry for bed and board on his journey.

It was a beautiful May morning, he tells us, when he took leave of his family, and set out, a mere child, lonely and heart-sore, to seek for knowledge; but he proceeded no farther than Granard, when his courage failed him. An ill-omened dream caused, doubtless, by over-fatigue, aroused his fears, and these, combined with the strong ties of domestic affections, deterred him from continuing his journey. He retraced his steps, and was received by his family with open arms and tears of joy, for they had suffered bitter pangs of remorse for having permitted one so young to go out upon the world alone.

Short as was his journey, it gave him an opportunity of forming a just estimate of the kindness and true delicacy of feeling of which the heart of the Irish peasant is possessed, and to which he has often paid grateful tribute.

An interval of about three years now elapsed before he was enabled to continue his scholastic career. Being designed, as we have said, for the church, he was not expected to labour upon the farm like the common herd; indeed his friends would have considered it exceedingly derogatory to a young gentleman who could give them a Latin or Greek quotation, and plenty of high-flown English, to take a spade into his hands, or to follow the plough. His own distaste for such occupations often prompted him, simple-minded as he was, to play upon the ignorance of his relatives, and to purchase exemption from such uncongenial tasks by exaggerating his literary acquirements, and, in the spirit of one of his own heroes, Denis O'Shaughnessy, he would not only give them a verse from the Greek Testament, but would translate it for them, and, in so doing, paraphrase it to such an extent, that it would require the wisest of commentators to discover its true meaning, or to explain it satisfactorily to the uninitiated.

During these three years the greater portion of his time was given up to athletic sports of every description, in all which he is said to have excelled. But the death of his father, and the declining circumstances of the family awoke him to a sense of the duties he owed to himself and his struggling relatives. He now saw that the course he had been pursuing promised no ultimate success in the career designed for him; and on learning, about this time, that the Rev. Doctor Keenan, a Catholic clergyman, and a cousin of his own, had opened a classical school at Glasslough, he sought him out, told him of the ties of blood which subsisted between them, and was received with kindness into the establishment. Here he remained for two or three years, at the expiration of which time he was obliged once more to return to his family, in consequence of the school at Glasslough having been removed to Dundalk.

When about nineteen years of age he abandoned the design of entering the church. No longer withheld by religious scruples, he now freely took part in all the sports and enjoyments of the people. Not a fair, wedding, christening, wake, or any other of those social pastimes of the peasantry, took place for miles around, at which he was not present. It was at this time, doubtless, that his mind became impregnated with that marvellous store of knowledge of Irish character, which has been transferred to the pages of his works. In tracing his career the reader will see that few other Irish writers ever possessed the same opportunities of studying the peasantry that were presented to him. Being one of the people, he was permitted to mingle freely in the various scenes of peasant life--the secret still-house, the fairs and markets, and their faction feuds, in which the darker passions of the Irish betray themselves. All these things were caught up and vividly retained by his impressionable mind for after delineation. He has held up to public blame the vices of the people--for where is the national heart without its stain?--but this he has done more in sorrow than in anger, and with the design that the moral which invariably accompanies these shadowings of their darker passions, may work in some degree the desired reformation. Wherever, then, there are extenuating circumstances he has urged them in their defence. To their piety, domestic affections, and many other virtues, as well as to their ready wit and humour, he has borne ample testimony.

That personal vanity, and even foppery, are sometimes associated with greatness of intellect, the history of England's noble poet sufficiently proves. The following anecdote will show that at one time of his life our author was not altogether free from these harmless blemishes. It was customary with him to start on a Saturday evening to an uncle's of his, who resided at some distance, and who had a family of four sons and two daughters, with whom he would remain for several days. These visits were always looked forward to by him and his worthy relatives with mutual pleasure. The girls were fine, blooming damsels, but some unaccountable desire, nevertheless, should seize upon them to imitate their faded sisters of fashion, and to exaggerate the rich tint which nature had bestowed upon their cheeks, by a liberal application of carmine, or some such colouring matter. It so happened that this fact became known to one of their brothers while their cousin was with them, and to him the secret was forthwith communicated. Now, as the girls considered this carmine to be a beautifier of their complexions, these two stalwarth young peasants did not see why they also should not profit by it, as a portion of it had fallen into their hands. Accordingly, on the following Sunday morning, they metaphorically "painted lily, and perfumed the rose," or, literally speaking, they painted the the roses of their own ruddy complexions, and set out in a very delectable frame of mind, reflecting upon the advantages their lightened attractions would give them over their compeers, in the eyes of the country maidens. But outraged nature was resolved to be revenged, and called the elements to her aid. A heavy shower, accompanied by a strong wind, which blew the rain remorselessly into that side of their faces exposed to it, came down, washing away all trace of the carmine from one cheek only. Had this been all, the vengeance would have been incomplete, and the fact of their having been guilty of such an egregious piece of vanity might never have transpired, as any change or improvement made by the carmine existed principally if not altogether in their own imaginations. It being washed from their faces, however, it was transferred to their shirt collars, of which there was no dearth in those days, and, therefore, the broad streaks which embellished them, and which could be justly traced to their source, made known the disparaging truth. Every eye was fixed upon them, and many found it impossible to restrain their laughter at the ludicrous appearance they presented; but it was while on their way home that the full power of their raillery was let loose upon them, and had the effect of putting them to the blush much more successfully than ever did the carmine. The only persons present who remained silent were those guilty bouncing females who had introduced the pretentious usage into simple peasant life.

As he had relinquished the idea of entering the church, his only alternative now seemed to be to fall back upon the resources of his forefathers, and become a tiller of the earth for his daily bread. This ill accorded with the spirit of romance which was springing up within him, or with the vague ambitious desires which were gaining strength with his boyhood. When he could succeed in procuring one of these novels full of startling and exciting incidents, which were rife in those times, work, food, and all such mundane considerations were disregarded, and he would sit or lie the whole length of a long summer day, in a green meadow under some shady, wide-spreading tree, in a perfect elysium, tracing, perhaps, the heart-rending career of some youthful damsel piteously afflicted with beauty and ardent adorers, or wrapt up in the relation of striking historical events. The classics, too, at this time, were closely studied --indeed it is principally to self-culture that he owes his education, as that which he acquired at school was very limited in comparison. Among the works of fiction which fell into his hands, was that relating to the adventures of the renowned Gil Blas. The history of this hero inspired him with so unconquerable a desire to mingle in more emotional scenes than those which his present life presented, that he left his home without any settled purpose, but with the inward conviction, inspired by hope and self-reliance, that he would succeed in working his way to independence, and gratify his desire for adventure, at the same time. He directed his steps to the parish of Killanny, in the county of Louth, the Catholic clergyman of which was nephew to his own parish priest. This clergyman's residence was close to the celebrated "Wild Goose Lodge," where, some months before, the fearful tragedy was enacted by which eleven persons were committed to the flames, through motives of personal vengeance. The circumstances connected with this hideous crime made a deep impression upon him, and formed the groundwork of one of his most powerful tales, which he has named after the scene of the tragedy. He has made this tale the medium of conveying friendly warning to the people of Ireland against Ribbonism, showing how many innocent and unsuspecting persons were drawn into its dark vortex of crime, and by its system of chance election to the most guilty offices, forced, in self-defence, to comply with its sanguinary laws. Like the terrible confederacy which had its origin in Westphalia, it was fatal to divulge its secrets, or to attempt to gain freedom from its destructive bonds.

Owing to the exertions of his friend the clergyman, our author was engaged as tutor in the family of a wealthy farmer named Piers Murphy, where he was supplied with board, lodging, and a rather limited salary; but, becoming dissatisfied, ere long, with the uncongenial task of mentally cultivating the young Murphys, and feeling that he was fitted for higher duties, he gave up his situation, and proceeded at once to the metropolis, which he entered with just two shillings and ninepence in his pocket. In the short space afforded in a memoir like this, we cannot trace him in his wanderings through the city in search of employment, with anything like minuteness. Various and oft-times ludicrous were the mistakes into which he fell, owing to his ignorance of life--especially of city life. The following circumstance is related as having occurred at this time.

Seeing, one day, an advertisement upon the window of a certain establishment, by which the public were informed that a person well skilled in the art of bird-stuffing was required, he entered, and addressing himself to one of the persons connected with it, offered his services.

"Are you quite sure you understand bird-stuffing thoroughly?" asked the individual applied to.

"Well, yes. I venture to say I do; I ought, at least, for I have seen a good deal of it at home in the country, and profited by it, too."

"And pray, what may be your method, my friend?" asked the taxidermist, who suspected he was committing a blunder, and thought he would amuse himself a little before he should have done with him.

"Why," replied our author, "the materials usually employed for stuffing fowl, in order to make them fat, are potatoes and oatmeal, and food of that description, forced down `will ye nil ye.'"

"Ah, my friend," said the other, smiling, "that sort of rough usage would never do for our birds; it would ruffle their plumage so much that the public would have nothing to say to them. They must have a respectable outside or it would little matter what was within."

"Ah!" replied Carleton, "I knew that hypocrisy was very general, but I never thought it was resorted to in bird stuffing!"

Another time, when driven to extremity, he thought of enlisting, but being above taking the shilling in the ordinary way, he wrote a long letter to the colonel of the regiment into which he designed to enter, informing him of his intention, and the circumstances that were driving him to take such a step. This epistle, which was written in very excellent Latin, was replied to in a spirit of kindness, expressive of the writer's regret that a person capable of writing such a letter should be forced to enter the ranks. The reply contained also an earnest admonition not to do so if he could by any possibility avoid it, which admonition was accompanied by a more substantial proof of kindness that gave force to the advice, as it enabled him to follow it.

It was owing to his knowledge of classics that he ultimately procured employment in Dublin. A few tuitions in private families, supplied him with just enough to subsist on. It was in one of these families that he first met with Mrs. Carleton, who resided with her uncle, father to one of his pupils. Although his means were so limited at this time, he attended the theatres constantly, and often denied himself a meal to spare the shilling that would enable him to indulge in the mental luxury of witnessing the performance of some theatrical star of his day, as in former times he had forgotten the demands of nature over some old time imaginings, or striking page in history.

It was impossible that a man of genius such as his should long be regarded as an ordinary person. His natural superiority and his attainments, so remarkable in a individual in his position of life, soon attracted the attention of men of education and intelligence. The graphic power, the brilliant wit, and the extraordinary humour and thrilling pathos which appear in his works evinced themselves in his conversation, and more especially in his recitals of events in his past life. It was therefore suggested to him by one of his friends to write of those things which he described with so much force in conversation. The result was his debut as a depicter of Irish life and character. His success was instantaneous, and in a short time he reached the zenith of his popularity. It was by no ordinary amount of application, however, that he arrived at that ease and perfection of style which mark even his earliest works. The conceptive powers of the brain are a free gift, but it requires energy and assiduity to perfect them.

He was now married, and an increasing family, as well as a desire for fame was urging him on. Those works which compose the volumes entitled "Traits and Stories of the Irish Peasantry," appeared in quick succession. He wrote with wonderful rapidity, for his mind was teeming with fact and imagery. His astonishing memory, too, yielded up its stores.

Distinction ever brings worshippers. His society was now eagerly sought by the higher classes of Dublin. Being of a social temperament, he found it impossible to resist the importunities of his friends, and was often obliged to sit up half the night to pursue his literary occupations in consequence of his remissness during the day.

Among literary men, more especially, no convivial meeting was considered complete if Carleton were not present. In the full vigour of his intellect he must have contributed in no slight degree to the brilliancy of those assemblings. Superiority, however numerous its admirers, will always attract a certain degree of envy, and it was hinted by some, that although Carleton's sketches and short stories were admirable, it was more than probable he would fail if he attempted works which would call for greater inventive powers. He had other kind friends who did not fail to communicate those remarks to him, and in a very short time after, the work which is by many considered the master-piece of his genius, "Fardorougha, the Miser," the first of his novels, appeared, and those who had predicted his failure were silenced.

Carleton, on leaving the north, made, as he says himself, a solemn resolution never to return unless with a name that should reflect honour upon himself and the place of his nativity. About fifteen or sixteen years since he visited the north, and was received by all parties and creeds with a fervour of affectionate acclamation almost unparalleled. On market days crowds of the people of every creed and denomination assembled before his hotel windows to catch a sight of him. On those occasions he went out into the town, and it is scarcely necessary to say that he drew nearly two thirds of the market after him.

Such of our readers as have read the "Poor Scholar," will remember the character of "Yellow Sam." Now, Yellow Sam was the actual nickname affixed upon that person in consequence of his bilious complexion, which was almost the colour of saffron. He was the most detested and detestable land agent in all that country, and his nieces were very angry, and heartily abused Carleton for having gibbeted him with such terrific and relentless satire. But what is strange, his nephew, the late Captain Miller of Daisy Hill, a most perfect, liberal, and honourable gentleman, had Carleton a frequent and welcome guest at his hospitable table. Dr. M'Nally, the present Catholic Bishop of Clogher, remarkable alike for his piety and his learning, also had him as his frequent guest. Gentry and peasantry received him with proud enthusiasm, negativing in this case the aphorism, which says that a prophet is without honour in his own country.

Many of Carleton's works have been translated into French and German. He has been told that some of them are translated into Italian, but of this he is not certain. A French version has recently appeared from the pen of the accomplished Leon De Wailly, under the auspices of Dentu, the bookseller and publisher who lives near the Palais Royale. "Valentine M'Clutchy" was translated into French fourteen years ago.

In private affairs Mr. Carleton is an indolent man, and very negligent of his own interests. His friends saw this, and came to the resolution of forming themselves into a committee, which they did, and held several meetings upon the subject of procuring him a pension. Two honorary secretaries were appointed. One of them was Stewart Blacker, Esq., nephew to the late Colonel Blacker, the author of that most spirited piece called "Oliver's Advice." It was Stewart Blacker who established the first Art Union in Ireland. In the true spirit of friendship and generosity, he applied himself to carrying out the design to benefit Carleton, when a pension of two hundred a year was granted in compliance with the request of the memorialists. No person out of Carleton's own family rejoiced more than he, at the success of the undertaking, in which he had himself so powerfully aided. The other honorary secretary was Thomas O'Hagan, the present Attorney-General, who omitted no exertions to promote Carleton's interests, as indeed did all the most distinguished and influential Irishmen and women of every creed and party. It was said that a memorial so numerously and respectably signed never was presented to a British minister. First on the list was the name of Lord Charlemont, who said: "Well, I never thought I should ask a favour from any government; but I look upon this not as an act of favour, but an act of justice." The late Maria Edgeworth, not satisfied with merely signing her name, suggested that if it were possible the memorial itself might be transmitted to her, and she requested that, if it were not too late, a space at the foot of it should be kept to enable her to give expression to her sentiments with respect to him. The memorial was immediately sent to her, and she wrote at the bottom of it as follows: "I have read all the works which Carleton has yet written, and I must confess that I never knew Irish life until I had read them. I have but little space to write what I wish to say; but my fervent desire is that Lord John Russell will take into earnest consideration the claims of this great but neglected man of genius."

For many years Carleton has given up society, and confined himself to the retirement of his own family circle. The Edinburgh Review of October, 1852, speaking of him, says:

`It is among the peasantiy that Mr. Carleton is truly at home. He tries other characters, rarely, however, and not unsuccessfully. But the Irish peasant is his strong point: here he is unrivalled, and writes like one who has had nothing to look out for, to collect by study, to select, to mould; who merely utters what comes spontaneously into his thoughts; from whom the language and sentiments flow as easily and naturally as articulate sounds from the human lips, or music from the skylark. Those who have in early life dwelt among the peasantry, and since forgotten that period in other and busier scenes of existence, meet again, in the pages of Carleton, the living personages of long past days, like friends returned from distant lands after an absence of many years.

"The primary and essential value of Mr. Carleton's sketches of Irish peasant life and character unquestionably consists in this--that they are true, and so true to nature; but it is enhanced by a circumstance similar to that recently recorded and lamented by Lord Cockburn in reference to Scotland. The living originals are disappearing; some of them have already disappeared. In Ireland, since our author's youth, changes, rapid and deep, have taken place, which, according to diversity of prejudice, and of the other causes that generate diversity of opinions, will be referred to different sources, and be brought to illustrate different political and social theories. Unless another master-hand should soon appear like his, it is in his pages, and in his alone, that future generations must look for the truest and fullest pictures of those who will ere long have passed away from that troubled land, from the records of history, and from the memory of men for ever * * * That field," adds the Edinburgh Review, alluding to Irish literature, "in which he stands without an equal among the living or the dead."

See also:--

William Carleton from The Dublin University Magazine, 1841