Treatment and Surgery

From A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland 1906

« previous page | contents | start of chapter | next chapter »

CHAPTER XIV....concluded

4. Treatment.

Hospitals.—The idea of a hospital, or a house of some kind for the treatment of the sick or wounded, was familiar in Ireland from remote pagan times. In some of the tales of the Tain we read that in the time of the Red Branch Knights there was a hospital for the wounded at Emain called Bróinbherg [Brone-verrig], the 'house of sorrow.' But coming to historic times, we know that there were hospitals all over the country, many of them in connexion with monasteries. Some were for sick persons in general; some were special, as, for instance, leper-houses. Monastic hospitals and leper-houses are very often mentioned in the annals. These were charitable institutions, supported by, and under the direction and management of, the monastic authorities.

But there were secular hospitals for the common use of the people of the tuath or district. These came under the direct cognisance of the Brehon Law, which laid down certain general regulations for their management. Patients who were in a position to do so were expected to pay for food, medicine, and the attendance of a physician. In all cases cleanliness and ventilation seem to have been well attended to; for it was expressly prescribed in the law that any house in which sick persons were treated should be free from dirt, should have four open doors, and should have a stream of water running across it through the middle of the floor. These regulations —rough and ready as they were, though in the right direction—applied also to a house or private hospital kept by a doctor for the treatment of his patients. The regulation about the four open doors and the stream of water may be said to have anticipated by a thousand years the present open-air treatment for consumption.

If a person wounded another or injured him bodily in any way, without justification, he was obliged by the Brehon Law to pay for "Sick maintenance," i.e. the cost of maintaining the wounded man in a hospital, either wholly or partly, according to the circumstances of the case, till recovery or death; which payment included the fees of the physician, and one or more attendants according to the rank of the injured person. Moreover, it was the duty of the aggressor to see that the patient was properly treated:—that there were the usual four doors and a stream of water; that the bed was properly furnished; that the physician's orders were strictly carried out—for example, the patient was not to be put into a bed forbidden by the doctor, or given prohibited food; and "dogs and fools and talkative noisy people" were to be kept away from him lest he might be worried. If the wounder neglected this duty, he was liable to penalty. Leper hospitals were established in various parts of Ireland, generally in connexion with monasteries, so that they became very general, and are often noticed in the annals.

Trefining or Trepanning.—In the Battle of Moyrath, fought A.D, 637, a young Irish chief named Cennfaelad [Kenfaila] had his skull fractured by a blow of a sword, after which he was a year under cure at the celebrated school of Tomregan in the present County Cavan. The injured portion of the skull and a portion of the brain were removed, which so cleared his intellect and improved his memory that on his recovery he became a great scholar and a great jurist, whose name—"Kennfaela the Learned"—is to this day well known in Irish literature. He was the author of the "Primer of the Poets," a work still in existence. Certain Legal Commentaries which have been recently published, forming part of the Book of Acaill, have also been attributed to him; and he was subsequently the founder of a famous school at Derryloran in Tyrone.

The old Irish writer of the Tale accounts for the sudden improvement in Kennfaela's memory by saying that his brain of forgetfulness was removed. It would be hardly scientific to reject all this as mere fable. What really happens in such cases is this. Injuries of the head are often followed by loss of memory, or by some other mental disturbance, which in modern times is cured, and the mind restored to its former healthful action—but nothing beyond—by a successful operation on skull and brain. The effects of such cures, which are sufficiently marvellous, have been exaggerated even in our own day; and in modern medical literature physicians of some standing have left highly-coloured accounts of sudden wonderful improvements of intellect following injuries of the head after cure. Kennfaela's case comes well within historic times: and the old Irish writer's account seems merely an exaggeration of what was a successful cure. We must bear in mind that the mere existence in Irish literature of this story, and of some others like it, shows that this critical operation—trefining—was well known and recognised, not only among the faculty but among the general public. In those fighting times, too, the cases must have been sufficiently numerous to afford surgeons good practice.

Stitching Wounds.—The art of closing up wounds by stitching was known to the old Irish surgeons. In the story of the death of King Concobar mac Nessa we are told that the surgeons stitched up the wound in his head with thread of gold, because his hair was golden colour.

Cupping and Probing.—Cupping was commonly practised by the Irish physicians, who for this purpose carried about with them a sort of horn called a gipne or gibne, as doctors now always carry a stethoscope. An actual case of cupping is mentioned in one old tale, where the female leech Bebinn had the venom drawn from an old unhealed wound on Cailte's leg, by means of two fedans or tubes; by which the wound was healed. It is stated in the text that these were "the fedans of Modarn's daughter Binn," a former lady-doctor, from which we may infer that they were something more than simple tubes—that they were of some special construction cunningly designed for the operation. We find a parallel case among the Homeric Greeks, where the physician Machaon healed an arrow-wound on Menelaus by sucking out the noxious blood and applying salves. The lady-physician Bebinn also treated Cailte for general indisposition by administering five successive emetics at proper intervals, of which the effects of each are fully described in the old text. Bebinn prepared the draughts by steeping certain herbs in water: each draught was different from all the others, and acted differently; and the treatment restored the patient to health. A probe (fraig) was another instrument regarded, like the cupping-horn, as requisite for a physician.

Sleeping-Draught.—In one of the oldest of the Irish Tales it is stated that the warrior lady Scathach gave Cuculainn a sleeping-draught to keep him from going to battle: it was strong enough to put an ordinary person to sleep for twenty-four hours: but Cuculainn woke up after one hour, This shows that at the early period when this story was written—seventh or eighth century—the Irish had a knowledge of sleeping-potions, and knew how to regulate their strength.

Materia Medica.—I have stated that some of the medical manuscripts contain descriptions of the medical properties of herbs. But besides these there are regular treatises on materia medica consisting of long lists of herbs and a few mineral substances, such as copperas and alum, with a description of their medical qualities, their application to various diseases, and the modes of preparing and administering them, the Latin names being given, and also the Irish names in case of native products. The herbs are classified according to the old system, into "moist and dry," "hot and cold."

The Irish doctors had the reputation—outside Ireland—of being specially skilled in medicinal botany.

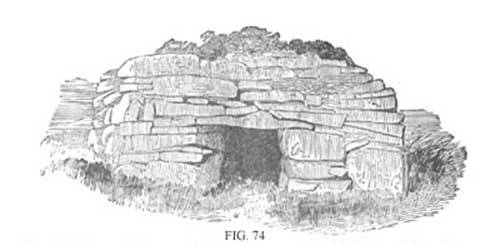

Vapour Bath and Sweating-House.—We know that the Turkish bath is of recent introduction in these countries. But the hot-air or vapour bath was well known in Ireland, and was used as a cure for rheumatism down to a few years ago. It was probably in use from old times; and the masonry of the Inishmurray sweating-house, represented opposite, has all the appearance—as Mr. Wakeman remarks—of being as old as any of the other primitive buildings in the island. The structures in which these baths were given are known by the name of Tigh 'n alluis [Teenollish], 'sweating-house' (allus, 'sweat'). They are still well known in the northern parts of Ireland—small houses, entirely of stone, from five to seven feet long inside, with a low little door through which one must creep: always placed remote from habitations: and near by is commonly a pool or tank of water four or five feet deep. They were used in this way. A great fire of turf was kindled inside till the house became heated like an oven; after which the embers and ashes were swept out, and water was splashed on the stones, which produced a thick warm vapour. Then the person, wrapping himself in a blanket, crept in and sat down on a bench of sods, after which the door was closed up. He remained there an hour or so till he was in a profuse perspiration: and then creeping out, plunged right into the cold water, after emerging from which he was well rubbed till he became warm. After several baths at intervals of some days he commonly got cured. Persons are still living who used these baths or saw them used.

Sweating-house on Inishmurray. Interior measurements: 5½ feet long, 4 feet wide; and 5 feet high. (From Kilk. Archaeol. Journal)

In the descriptions of the various curative applications given in old Irish medical books there is an odd mixture of sound knowledge and superstition, common in those times, not only among Irish physicians, but among those of all countries. Magic, charms, and astrological observations, as aids in medical treatment, were universal among physicians in England down to the seventeenth century.

Popular Herb-Knowledge.—The peasantry were skilled in the curative qualities of herbs and in preparing and applying them to wounds and local diseases; and their skill has in a measure descended to the peasantry of the present day. There were "herb-doctors," of whom the most intelligent, deriving their knowledge chiefly from Irish manuscripts, had considerable skill and did a good practice. But these were not recognised among the profession: they were amateurs without any technical qualification; and they were liable to certain disabilities and dangers from which the regular physicians were free, like quack-doctors of the present day. From the peasantry of two centuries ago, Threlkeld and others who wrote on Irish botany obtained a large part of the useful information they have given us in their books. Popular cures were generally mixed up with much fairy superstition, which may perhaps be taken as indicating their great antiquity and pagan origin.

Poison.—How to poison with deadly herbs was known. The satirist Cridenbel died by swallowing something put into his food by the Dagda, whom the people then accused of murdering him. After Coffagh the Slender of Brega had murdered his brother Laery Lorc, king of Ireland, he had Laery's son Ailill murdered also by paying a fellow to poison him.

END OF CHAPTER XIV.

« previous page | contents | start of chapter | next chapter »