Penwork and Book Illumination

From A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland 1906

« previous page | contents | next page »

Sculpture on a Capital, Church of the Monastery, Glendalough: Beranger 1779 (From Petrie’s Round Towers)

CHAPTER XII.

SECTION 1. Penwork and Illumination.

IRELAND art was practised chiefly in four different branches:—Ornamentation and Illumination of Manuscript-books: Metal-work: Stone-carving: and Building. In Leather-work also the Irish artists attained to great skill, as we may see in several beautiful specimens of book-binding still preserved. Some branches of art were cultivated—as we shall see—in pagan Ireland; but art in general reached its highest perfection in the period between the end of the ninth and the beginning of the twelfth century.

The special style of pen ornamentation, which in its most advanced stage is quite characteristic of the Celtic people of Ireland, was developed in the course of centuries by successive generations of artists who brought it to marvellous perfection. Its most marked characteristic is interlaced work formed by bands and ribbons, which are curved and twisted and interwoven in the most intricate way, something like basket-work infinitely varied in pattern. These are intermingled and alternated with zigzags, waves, spirals, and lozenges; while here and there among the curves are seen the faces or forms of dragons, serpents, or other strange-looking animals, their tails or ears or tongues not unfrequently elongated and woven till they become merged and lost in the general design; and sometimes human faces, or fall figures of men or of angels. But vegetable forms are very rare. This ornamentation was commonly used in the capital letters, which are generally very large: one splendid capital of the Book of Kells covers a whole page. The pattern is often so minute and complicated as to require the aid of a magnifying glass to examine it. The penwork is throughout illuminated in brilliant colours, in preparing the materials of which the scribes were as skilful as in making their ink: for in some of the old books the colours, especially the red, are even now very little faded after the lapse of so many centuries.

We have many books ornamented in this style. The Book of Kells, a vellum manuscupt of the Four Gospels in Latin, written in the seventh or eighth century, is the most beautifully written book in existence. Miss Stokes, who has examined it with great care, thus speaks of it:—"No effort hitherto made to transcribe any one page of this book has the perfection of execution and rich harmony of colour which belongs to this wonderful book." Professor J. O. Westwood, of Oxford, who examined the best specimens of ancient penwork all over Europe, speaks even more strongly:—"It is the most astonishing book of the Four Gospels which exists in the world. ... I know pretty well all the libraries in Europe where such books as this occur, but there is no such book in any of them; . . . there is nothing like it in all the books which were written for Charlemagne and his immediate successors."

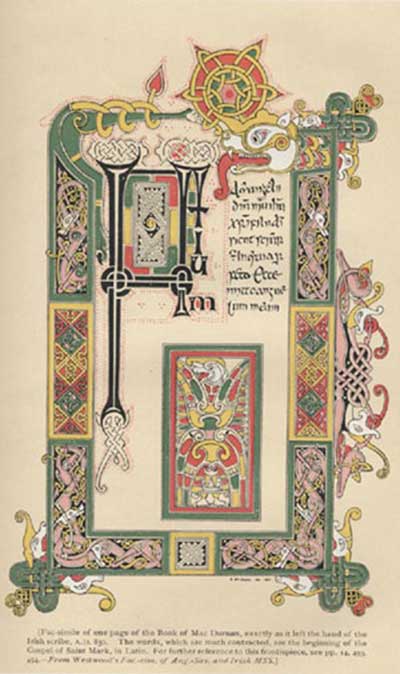

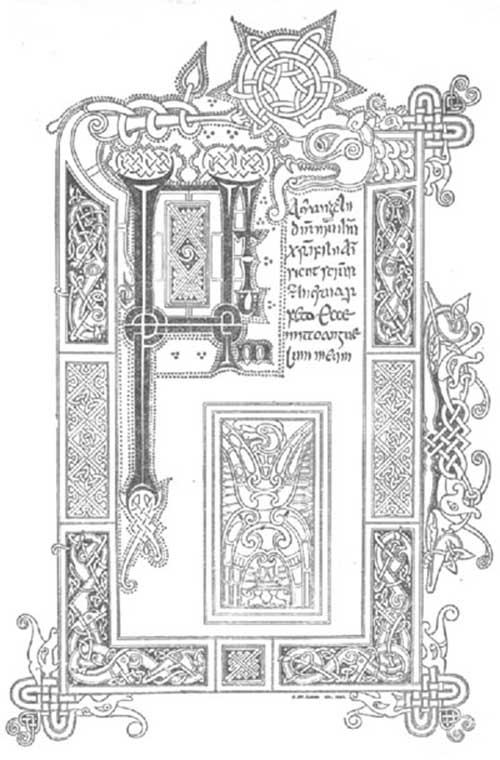

FIG. 64A. Fac-simile of one page of the Book of Mac Durnan, exactly as it left the hand of the Irish scribe, A.D. 850. The words, which are much contracted, are the beginning of the Gospel of Saint Mark, in Latin.

The Book of Durrow and the Book of Armagh, both in Trinity College, Dublin; the Book of Mac Durnan, now in the Archbishop's Library, Lambeth; the Stowe Missal in the Royal Irish Academy; and the Garland of Howth in Trinity College—all written by Irishmen in the seventh, eighth, and ninth centuries—are splendidly ornamented and illuminated: and of the Book of Armagh, some portions of the penwork surpass even the finest parts of the Book of Kells.

FIG. 64. Outline of the illuminated page from the Book of Mac Durnan.

Latin words fully written out:—Initium Aevangelii domini nostri ihesu christi filii dei sicut scriptum est in esaia profeta Ecce mitto anguelum meum.

Translation:—The beginning of the Gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ Son of God as it is written in Esaia the prophet Behold I send my angel.

Giraldus Cambrensis, when in Ireland in 1185, saw a copy of the Four Gospels in St. Brigit's nunnery in Kildare, which so astonished him that he has recorded—in a special and separate chapter of his book—a legend that it was written under the direction of an angel.

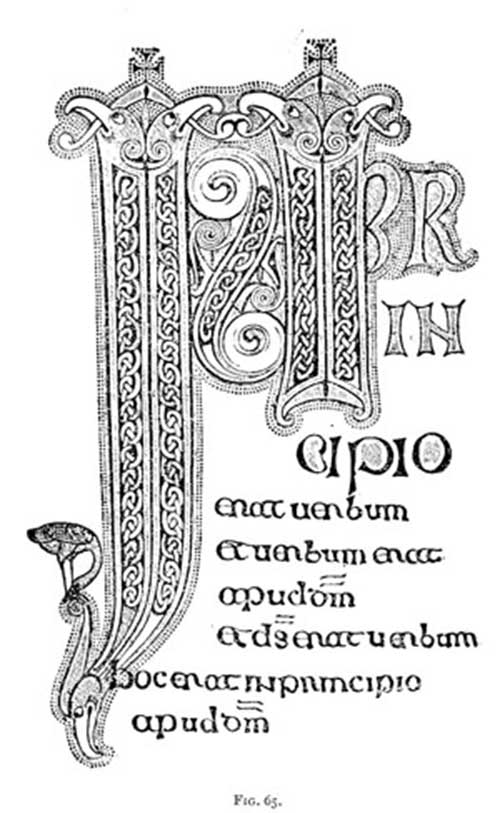

FIG. 65. The beginning of the Gospel of St. John, from an Irish manuscript Gospel Book now in Bavaria. (In the original MS., this is illuminated in colour).

This beautiful art originated in the East—in Byzantium after the fall of the first empire—and was brought to Ireland—no doubt by Irish monks, or by natives of Central Europe who came to Ireland to study—in the early ages of Christianity. But as first introduced it was very simple. Though the Irish did not originate it, they made it, as it were, their own after adopting it, and cultivated it to greater perfection than was ever dreamed of in Byzantium or Italy. Combining the Byzantine interlacings with the familiar pagan designs at home, they produced a variety of patterns, and developed new and intricate forms of marvellous beauty and symmetry. Accordingly it is now known by the name Opus Hibernicum, 'Irish Work.' Irish manuscript books, ornamented in this manner and richly illuminated, are found, not only in Ireland, but in numerous libraries all over Great Britain and the Continent. (See illustration, last page.)

In pagan times the Irish practised a sort of ornamentation consisting of zigzags, lozenges, circles both single and in concentric groups, spirals of both single and double lines, and other such patterns, many very beautiful, which may be seen on bronze and gold ornaments preserved in museums, and on sepulchral stone monuments, such as those at New Grange and Loughcrew. But in all this pre-Christian ornamentation there is not the least trace of interlaced work.