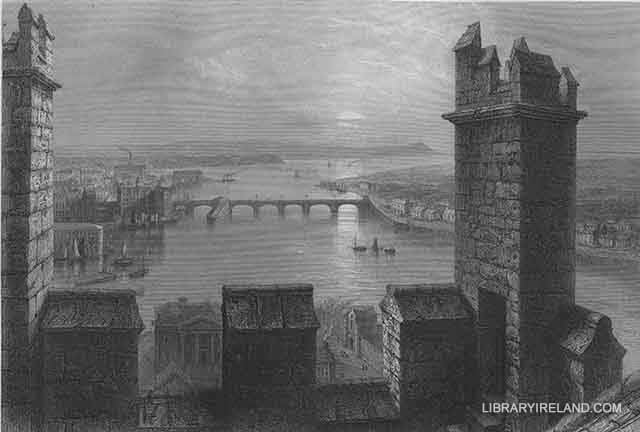

View of Limerick and the Shannon from the Cathedral Tower

An American traveller could scarcely enter Limerick without exclaiming in the principal street, "How very like New York!" The tall and handsome brick-houses, the iron railings, the broad and clean side-walks, and something in the dress and style of the people, would remind him very forcibly of his native country. There was a chapel-bell ringing for an evening lecture when we arrived (it was just twilight), and well-dressed persons were coming to it from all quarters —and this church-going feature perhaps contributed its share to the resemblance. We had two hours of day-light ramble through the town before the evening shut in; and we must record our agreeable surprise at the beauty and thriftiness of the fair town of Limerick. In the morning we rose early, and mounted to get a view of LIMERICK AND THE SHANNON FROM THE CATHEDRAL TOWER.

This fine river, with its handsome bridges, gives a grandeur to the view which would otherwise be wanting to so flat a country; yet, in the charms of cultivation and quiet loveliness, the panorama from this elevated point is well worth the seeking. Our guide called on us to admire the size of the bells, and with the words "Limerick bells," the story connected with them at once, and for the first time since our arrival in the town, recurred to our memory.

"The remarkable fine bells of Limerick," so runs the story, "were originally brought from Italy, they had been manufactured by a young native (whose name tradition has not preserved), and finished after the toil of many years, and he prided himself upon his work. They were subsequently purchased by the prior of a neighbouring convent; and with the profits of this sale the young Italian procured a little villa, where he had the pleasure of hearing the tolling of his bells from the convent-cliff, and of growing old in the bosom of domestic happiness. This however was not to continue: in some of those broils, whether civil or foreign, which are the undying worm in the peace of a fallen land, the good Italian was a sufferer amongst many. He lost his all; and, after the passing of the storm, found himself preserved alone amid the wreck of fortune, friends, family, and home. The convent in which the bells, the chef-d'oeuvre of his skill, were hung, was razed to the earth, and these last carried away to another land.

The unfortunate artist, haunted by his memories and deserted by his hopes, became a wanderer over Europe. His hair grew grey, and his heart withered before he again found a home and a friend. In this desolation of spirit he formed the resolution of seeking the place to which those treasures of his memory had been finally borne. He sailed for Ireland, proceeded up the Shannon; the vessel anchored in the pool near Limerick, and he hired a small boat for the purpose of landing. The city was now before him, and he beheld St. Mary's steeple, lifting its turreted head above the smoke and mist of the old town. He sat in the stern and looked fondly towards it. It was an evening so calm and beautiful as to remind him of his own native haven in the sweetest time of the year—the depth of the spring. The broad stream appeared like one smooth mirror, and the little vessel glided through it with almost a noiseless expedition. On a sudden, amid the general stillness, the bells tolled from the cathedral; the rowers rested on their oars, and the vessel went forward with the impulse it had received. The old Italian looked towards the city, crossed his arms on his breast, and lay back in his seat; home, happiness, early recollections, friends, family—all were in the sound, and went with it to his heart. When the rowers looked round they beheld him with his face turned towards the cathedral, but his eyes were closed, and when they landed they found him cold!"