War and Conciliation

A Short period of hope had intervened when, in May, 1917, it was proposed that a Convention should be held in Dublin lor the purpose of drafting a Constitution for the country. “We propose,” said Mr. Lloyd George, “that Ireland should try her own hand at hammering out an instrument of government for her people.”

The Convention, in which Sinn Féin took no part, met for the first time on July 25 and Sir Horace Plunkett was unanimously elected Chairman. It sat through the autumn and winter but failed to come to any unanimous conclusion, Ulster refusing to make any further concessions.

Great good sense and good feeling were manifested throughout the discussions, Lord Midleton especially, speaking for the Southern Unionists, being earnest in his endeavours to find a compromise, but difficulties arose over finance and in regard to a fiscal policy for Ireland, and the effort to mediate between Ulster and the Home Rulers broke down. The Ulstermen argued that they only wanted to be let alone with their rights safeguarded.

In the division on the question of Customs, in which the Nationalists of Redmond’s party voted with the Southern Unionists and several Labour delegates against the combination of the Ulstermen and a section led by Mr. Devlin, a majority of 38 to 34 was declared, and it became a question whether the Government would consider that this result gave the “substantial agreement” stipulated for when the Convention began. In the General Report, 66 out of 87 concurred on the broad lines of debate, the minority being largely composed of the group which refused to accept any form of Home Rule.

This was a very considerable measure of agreement. But, on March 6, 1918, John Redmond, worn out by anxieties, died; and in the press of the great offensive of the German troops and the push back of the Allies, Home Rule was dropped; instead of bringing in a measure immediately on the presentation of the Report, conscription for Ireland was declared. Though it was never enforced, the threat at this moment served to let loose anarchy in Ireland.

In the meantime Sinn Féin had been active elsewhere. In prospect of the Convention the Government had proclaimed a general amnesty and most of the interned or imprisoned men had returned home. Their leaders now called a Convention or Ard-Fhéis of their own, attended by 1,700 delegates from the four Provinces of Ireland, which elected Mr. De Valera President, a post held during the previous years by Arthur Griffith.[1] Mr. De Valera had been one of the last to hold out in the rebellion of Easter Week and he had been condemned to death, but his sentence was commuted to penal servitude. He had recently been released from Lewis Gaol, having been nominated for Clare while he was still in prison, and he now became the rallying-point for the new movement.

The leaders met in Conference at the Mansion House with Mr. John Dillon and other members of the old Irish party, but they found little common ground, while on the other hand, Sinn Féin absorbed into itself the various associations which had been sympathetic to republicanism in any form. Clubs were founded, funds seemed always to be forthcoming, and the military organization grew daily stronger; the young men who had resisted conscription for foreign service flocked by hundreds into the Republican army, attracted by the hope of pay and the love of adventure, as well as by more patriotic motives. They had few trained officers, but they picked up their military knowledge from the official books supplied to British troops, and from the exigences of insurgent warfare. From the moment of the announcement of conscription, many of the priests took the side of the Republicans.

In 1918 it was said that 80 per cent.[2] of the inhabitants of Galway were Sinn Féiners and in the election of that year, out of 105 members returned for the whole of Ireland, 73 were for Sinn Féin. Of these elected members, 36 were in prison, and four deported; only thirty appeared at the sitting. But the claim now made was that of complete independence, with the recognition of Ireland as a separate nationality.

On the 21st January, 1919, the newly elected members met at the Mansion House and set up an Irish ministry. They reaffirmed the claim of Ireland to independence and proclaimed the establishment of an Irish Republic; at the same time sending a message to the nations announcing their re-entry into separate nationality. It was the first meeting of Dáil Éireann, and it proceeded to make its position effective by capturing local Councils, and setting up Arbitration Courts, which in the terror of the next two years continued to administer justice through the country with general approval, while English law went unheeded; it established an economic commission to enquire into Irish agricultural and mineral resources, and discussed alterations in the educational system.

In two important efforts the Dáil failed to secure attention. One was the presentation of Ireland’s case before the Peace Conference, which in spite of persistent Irish propaganda on the Continent and in America, was turned down; the other was an appeal to President Wilson for recognition, but this also was refused. The leaders claimed, with great justice, that Ireland was one of the “small nations” about which the Liberal party were flinging phrases broadcast, and on behalf of whom the war was said to have been fought. The English Government’s reply was to proclaim all their acts illegal, and to endeavour to suppress them by force. There were for a period two Governments in Ireland, one acting from outside and upheld by force, the other illegal and often “on the run” but upheld by popular sympathy and implicitly obeyed over large parts of the country.

The Volunteers, now re-christened as the Irish Republican Army, though not formidable as to numbers, were well disciplined, and as their raids on police barracks and private houses increased they became sufficiently armed with excellent weapons. They were recruited from a good class among the population, farmers’ sons, schoolmasters, and peasants, who permitted no indulgence or drunkenness in their ranks, and who obeyed orders without questioning from their commanders. They increased rapidly, over 500 men joining their ranks on the day young Kevin Barry was hanged.

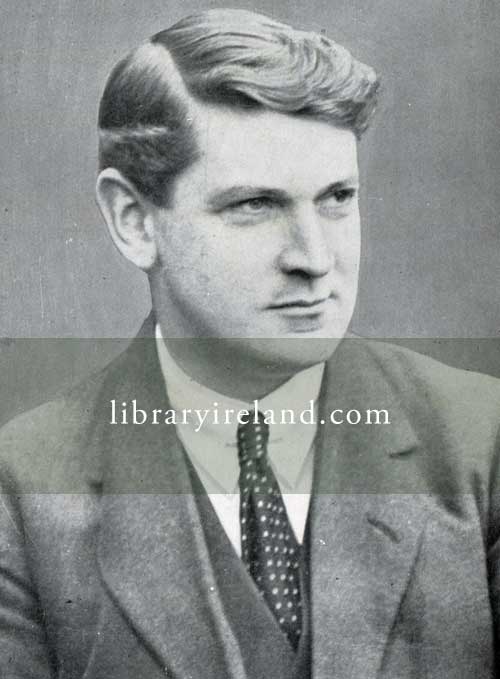

Michael Collins.

Early in the struggle, their future Commander-in-Chief, Michael Collins, whose escapes and adventures made him almost a legendary figure, became prominent for his marvellous powers of organization and his incessant activity. When the chief leaders of Sinn Féin were arrested and deported on suspicion of a German plot, Michael Collins occupied himself with forming the loosely knit remnant of the Volunteers into a solid and serviceable body. Though he had only returned to Dublin in January, 1916, after spending the early part of his life in London, he speedily gathered up the strings of the movement into his own hands, and became its acknowledged centre.

“The movement as a whole became aware of him, sensed his personality and his leadership, began to love him and to have that trust in him which hitherto they had had in Griffith and de Valera … They found Collins doing everything and leading everything and trusted by everybody. He had won his place.”[3]

He laid his plans in a systematic manner. His first aim was to outwit and terrorise the members of the Government Secret Service, and to establish a counter-organization which controlled the post office and obtained regular information of the official Castle plans. Spies within the ranks of his own army were tracked and warned, and every man in its ranks was thoroughly tested. By means of “a steady cleaning-up” it was “made unhealthy for Irishmen to betray their fellows and deadly for Englishmen to exploit them.”[4]

Next the “G” division of the English Secret Service was undermined, and terrible examples were made, the murder of fourteen British officers, believed to be in the Secret Service, on Sunday morning, November 21, 1920, being one of the most dreadful of these acts of vengeance. Reprisals took place on the same afternoon, when the military fired on and killed a number of innocent persons attending a football match at Croke Park.

Having perfected his intelligence system, Collins next set himself to establish centres, of which Cork, the headquarters of General Strickland, was the chief, from which he could spread his flying columns throughout the country. The effectiveness of these flying columns was testified to during the discussions on the Treaty by Mr. Lloyd George, when the question of Ireland’s right to possess submarines came up. “Submarines,” said the Prime Minister “are the flying columns of the seas … and I am sure there is no need to tell you, Mr. Collins, how much damage can be inflicted by flying columns! We have had experience with your flying columns on land.”

Gradually the police and Royal Irish Constabulary were forced to concentrate in specially armoured barracks, often at considerable distances from each other, and upon these attacks were constantly made; while raids and ambushes became of daily occurrence. Ambushes were resorted to both for the purpose of entrapping military or constabulary and in order to capture arms and explosives, the first important take being that at Soloheadbeg Quarry where a quantity of gelignite, intended for quarrying purposes, was captured in January, 1919, by a party of youths who wished to force more active warfare on their comrades, and in which adventure two policemen were killed.

The life of Lord French, who came over in May, 1918, as Viceroy, was attempted near the Ashtown gate of Phœnix Park by the same band of irresponsible men on December 19 of the following year, but he escaped by travelling in his car in a different order from that which he usually took.

The murder policy was not popular in the country and was disapproved even by the military leaders of the Republican party. Dan Breen, the organizer of many of these outrages, says that neither General Headquarters nor Dáil Éireann sanctioned it or accepted responsibility.[5] But as the “war” went on, it became more merciless and the larger part even of the more moderate men were drawn into it, until such terrible deeds as the shooting to pieces of seven lorry-loads of Auxiliaries at Macroom passed without exciting surprise.

The country people sheltered and helped the insurgent forces, concealing the hunted men and supplying them with food, money and munitions. In no other way could the struggle have lasted so long. Attacks on police barracks were frequent and between January, 1920, and the beginning of the following year, there were 23 occupied barracks destroyed and 49 damaged. Many more vacated barracks were burnt down. During the same period, 165 members of the police force were killed and 225 wounded, besides civilians murdered, kidnapped or terrorized.[6]

Funds were seized or called for under threats of punishment and raids for arms were frequent. One of the worst cases of kidnapping with murder was that of a lady and her manservant who were carried off at night from near Macroom and never again heard of. They were accused of having warned the police of an intended ambush. The sensational rescue of Sean Hogan from the train at Knocklong in May, 1919, was eclipsed by the still more startling rescue of Mr. de Valera from Lincoln Gaol three months before, and his subsequent public appearance in Ireland and America in defiance of the police.

It will always be a question whether the campaign of murder and arson which made life terrible in Ireland during the late years of the Great War was begun by the advocates of Irish rebellion or those of English repression. Lloyd George asserted that no “reprisals” had taken place on the part of the police or military until a hundred policemen had been assassinated. But Irishmen contended that before any crime had been committed on their part after the date of the Rebellion in 1916, existence had been rendered intolerable by the raids, arrests, and deportations without trial by the military authorities.

A certain amount of caution has to be exercised in accepting reports made by interested parties on both sides, often for propaganda purposes. It seems certain however that in 1918, over 1,100 political arrests had been made, 77 deportations, and 260 raids on private houses for the purpose of search for persons or for incriminating documents. Besides these, there had been cases of murder of civilians for which no punishment had been inflicted.[7]

The arrival of Lord French in May, 1918, as Viceroy, with Mr. Shortt as Chief Secretary was the signal for a policy of ever-increasing repression. From January, 1919, to March, 1920, raids on houses had risen to 22,279, while political arrests numbered 2,332. Newspapers were suppressed, as were all organizations believed to have a republican tendency. The murders of the Lord Mayor of Cork, Thomas MacCurtain, and of the Mayor of Limerick, Michael O’Callaghan, excited great and just indignation.

Attempts were made to suppress markets and fairs such as those held at Cashel, Nenagh, Clonmel and Thurles, and to dismantle creameries, on the plea that they were meeting-places for malcontents. Even the landlords protested that such acts did not diminish the number of murders but that they ruined and exasperated the country. Later on, towns and villages were “shot up” either as reprisals for murders of policemen or as the act of drunken and undisciplined soldiers, a number of the principal buildings in Cork,[8] and the towns of Fermoy, Lismore, Balbriggan, Tuam and many others being partly or entirely destroyed in this savage manner.

Some of these “reprisals” were admitted by the Government and they aroused much anger in England. The military advisers spoke of “authorised” and “unauthorized” reprisals, and the Government left it to the military to decide which were to be carried out.

In October, 1920, Mr. Winston Churchill said that the army in Ireland was costing £210,000 a week[9] and at the moment when conscription was proposed there were nearly 60,000 troops in the country, besides the Dublin Metropolitan Police and the 10,000 men of the Royal Irish Constabulary, who were an armed body recruited from a good class of the population and stationed in small barracks in the country districts. But these were beginning to fall off, partly through sympathy with the insurgents, many of whom were their intimate friends and relations, and partly through the misery to which they were subjected by constant ambushes and unforeseen attacks. In June, 1920, resignations at the rate of nearly a hundred in that one month were being handed in, and Sir Hamar Greenwood stated in the House that, between January 1 and July 16, 250 men had resigned.[10]

It was partly to make up for this depletion in the ranks that after the arrival in April, 1920, of Sir Hamar Greenwood as Chief Secretary, it was decided to augment the forces by sending over some 15,000 new recruits, men largely chosen from the ex-officers of the war, often young cadets glad of fresh occupation and looking on the free life they expected to find in Ireland and the work they were called upon to do much as a sportsman might enjoy the thought of “good sport.”

Along with these men, known as the Auxiliary Police Force, came a number of men, many of them of low class, who have left behind them a bitter memory in Ireland. These men were styled by the people with ready wit the “Black and Tans,” from the strange medley of dark green police uniform and khaki in which they were hastily fitted out from the deficient military stores; they reminded the populace of a famous pack of hounds belonging to the district in South Tipperary to which they were sent. Ill-disciplined and without competent officers, these men speedily established a reign of terror even in districts that hitherto had been quiet. All semblance of military discipline vanished and henceforth it became impossible to distinguish by which side or for what purpose acts of violence and cruelty were committed.

Law and order disappeared and a reign of terror took its place. The Government talked of an atmosphere of conciliation in one breath and of reprisals and coercion in the next, while Sir Nevil Macready and Sir Henry Wilson demanded that over the whole of Southern Ireland martial law should be proclaimed and loudly deprecated any half measures. As the war lengthened it became on both sides “more brutal and more savage and more unrelievedly black,” its worst effect being on the women, who forgot their normal role in life and became the hysterical advocates of war. Ireland was given up to the gunman and the gunwoman.[11] The country suffered a moral collapse.

Among the embarrassing incidents of the position was the use of the hunger-strike, adopted in the gaols by the interned and arrested men as a protest against the arrest and imprisonment of untried persons, or their trial by courts-martial. Hunger-strikes went on for lengthened periods at several prisons, especially at Wormwood Scrubs, and excited much public sympathy. It was an unconscious return to the ancient habit of “fasting upon” a creditor so much in vogue in early Ireland, that is, forcing him out of pity to grant demands otherwise unheeded. The suffragettes had set an example of this return to ancient methods and it was adopted by many of the prisoners.

Thomas Ashe, during a hunger-strike at Mountjoy, had died as the result of forcible feeding. In the autumn of 1920, in Brixton Gaol, the long drawn out agony of Terence MacSwiney, who had been elected Lord Mayor of Cork on the death of Thomas MacCurtain, riveted on the dying man the attention of the whole civilised world. On both sides it was regarded as a test case. MacSwiney had been more than once interned or imprisoned for Sinn Féin activities as Commandant of the First Cork Brigade of the Republican Army; but apart from his hatred of all things British, he was held to have been personally a just man, respected for his character and abilities.[12] It was this personal attraction that made his long suffering and the courage with which he bore it a cause of sympathy even to people who differed from him fundamentally in opinion.

The Government had again and again released Irish prisoners who had adopted the hunger-strike and MacSwiney had himself been released on this ground in 1917 without serving his sentence. It was becoming an accepted doctrine that it was only necessary to go on hunger-strike to secure release from gaol. It was evident that this must be brought to an end, and while everything was done to prolong the life of MacSwiney—food, nurses, doctors and all possible alleviations being provided for him—he was not released. His own friends were equally determined; and Terence MacSwiney was permitted to die. He was accorded a public funeral through the streets of London with the full consent of the authorities. From that date hunger-striking ceased. The strike going on at the same time in Cork Prison was called off, Arthur Griffith having written that “as these men were prepared to die for Ireland, they should now again prepare to live for her.” Two of them had died, after a still longer abstinence than that of MacSwiney.