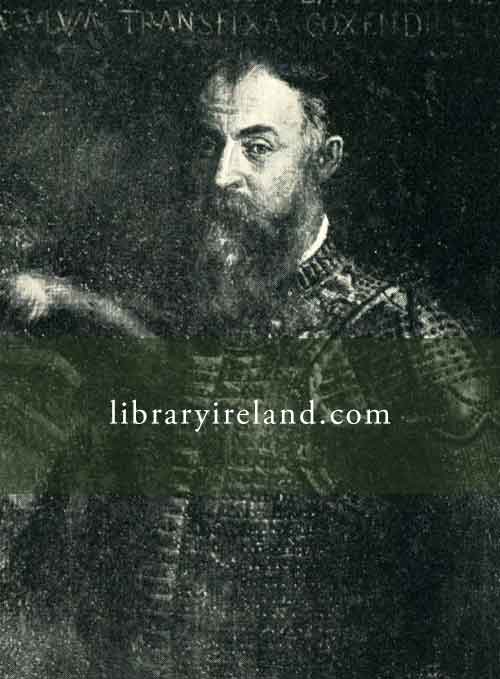

Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone

It is curious to reflect that the two men who are accounted the greatest representatives of the race of the O’Neills—Hugh, Earl of Tyrone, and Owen Roe O’Neill—may neither of them have been members of the O’Neill family, but were possibly the offspring of some otherwise unknown clansman of another name and ancestry. As we have seen, Hugh’s father, Ferdoragh, called by the English “Matthew,” and created by them at Conn’s request Baron of Dungannon, was not acknowledged as an O’Neill by his own people or by Shane.

The popular suffrage would never allow that he was even Conn’s illegitimate son, and the sept steadily supported Shane against him till Shane cleared his own path to the chieftainship by putting him out of the way early in his career. Hugh was this Matthew’s second son, his elder brother having been put to death by Turlogh Lynogh O’Neill as a possible rival. Hugh was thus either Conn’s bastard grandson, which by Irish usage might have been no impediment to his taking a position in the family or clan; or he was, with still greater probability, no relation at all.[1]

Similarly, Owen Roe O’Neill was a son of Art, a natural son of Matthew, and thus again of doubtful paternity. But, whether legitimate descendants of the race of The O’Neill or not, these two bearers of the title worthily sustained the honour of the name and added lustre to it.

Hugh, like his father, had been accepted by the English, and was supported by them against Turlogh, as they had supported Matthew against Shane. “He is the hope of all,” wrote an Anglican bishop at a later date.

Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone

Born about 1545, he was brought up with other royal wards at the English Court, among the young nobles and officers who were later, like himself, to play their part on the Irish stage. Like them, he served in the English army, and commanded a troop of horse in the Munster wars against Desmond. Gainsford says that in his youth Hugh “trooped in the streets of London with sufficient equipage and orderly respect.” [2]

In his home life in later days he encouraged the cultivated atmosphere of a refined gentleman, and he brought up his boys in the manner of young courtiers. There is a description of a visit of state paid to the Earl in 1599 by Sir William Warren, accompanied by Sir John Harington, the loquacious and witty translator of Ariosto, a vain, good-natured, and inquiring man, who has left us several interesting items of information about the experiences of himself and his cousins in Ireland.

While Warren was engaged with Tyrone in discussing the purpose of his visit, Sir John took the opportunity of amusing himself with the Earl’s two boys and a young scholar who was studying with them under their tutor, the Franciscan Friar Nangle, and examining them in their learning. He found the two lads “of good towardly spirit,” their ages between thirteen and fifteen, dressed in English clothes like a nobleman’s sons, with velvet jerkins and gold lace; of a good cheerful aspect, and both of them learning the English tongue.[3]

Sir John presented the lads with a copy of his Ariosto, which their instructor took very thankfully, and afterward showed to the Earl, who must needs hear some part of it read, and seemed to like it so well that he solemnly swore that his boys should read all the book over to him. When the business of the meeting—the signing of a cessation of hostilities, “which he would never have agreed to, but in confidence of my Lord’s [Essex’s] honourable dealing with him”—was over, the ambassadors dined with Tyrone.

“At his meat he was very merry, drank to my Lord’s [Essex’s] health, and bade me tell him he loved him, and acknowledged that this cessation had been very honourably kept.”

He praised the valour of Sir John’s cousin, Sir Henry, and discoursed like a courteous and cultivated man of the world. Sir John also describes an al fresco feast “spread on a table of fern under the stately canopy of heaven.” O’Neill’s guard, for the most part, were beardless boys without shirts: who, in the frost, waded as familiarly through rivers as water-spaniels. Sir John adds:

“With what charm such a master makes them love him I know not, but if he bid come, they come; if go, they do go; if he say do this, they do it.”

This charming picture of O’Neill’s home life at Dungannon, near the waters of Lough Neagh, gives us, as it gave Harington, a new view of the Ulster “arch-rebel,” and one that it is useful to bear in mind when we read of his wars and misfortunes.

O’Neill, like Florence MacCarthy in Munster, was never a willing rebel; he knew the power of England, and he liked many of the men among whom he had grown up, and was liked by them in return. His protest “that he was not ambitious, but sought only safety for his life and freedom of his conscience, without which he would not live though the Queen should give him Ireland,” may have been perfectly true at this time; but his ambition grew with altered circumstances, and in later days he definitely aimed at being ruler of a united Catholic Ireland.

Hugh was the most English of all the O’Neills, and his desire to marry an English wife, however it may have been dictated as an act of policy, shows his intention to keep in touch with English life. His courtship of Mabel, sister to the Marshal Sir Henry Bagenal, was a romantic one, and only a man of determination would have ventured to carry it through. Mabel met O’Neill at Newry, soon after the death of his first wife, the sister of Red Hugh O’Donnell. He grew to have for her “a wonderful affection,” and by every kind of entreaty sought leave to make her his wife.

The Marshal saw many difficulties, and sent her away to the house of her sister, Lady Barnewall, near Dublin, in order to get her out of the way. But Tyrone, through trusted friends, was allowed to see her, and they plighted their troth with due solemnity, being married shortly afterward “very honourably according to her Majesty’s laws” at a friend’s house by the Bishop of Meath.

Hugh carried his young bride of twenty off with him to his own country, “using her very kindly and faithfully, and promising to have an honourable regard of her to the contentment of her friends and allies hereafter.”[4] But Bagenal, when he heard of the marriage, was overcome with “unspeakable grief.” He considered that a stain had been cast on his family by his sister’s marriage with a “rebellious race, which he and his father had spilled their blood in repressing,” and he feared that his own loyalty and consequently his position were endangered by such an alliance. He never forgave it, and henceforth pursued Tyrone with unrelenting hatred, never losing an opportunity to do him ill. He refused also to give him the dower due to him as his sister’s husband: a matter which was the cause of much dissension between them.

It cannot be said that the marriage was a happy one. Fidelity was a thing unknown in Ulster, and when Mabel found that her husband “did affect other gentlewomen” she grew to dislike him and went to her brother to complain of his treatment of her. She died a year or two later; mercifully she did not live to see her brother slain by her husband’s hand.

Much of Hugh’s life after his return from England was taken up by disputes with Turlogh O’Neill for precedence. Turlogh had, as we have seen, been accepted by the sept as ‘O’Neill,’ and regularly inaugurated, and the Queen’s offers to Hugh of the titles of Baron of Dungannon or Earl of Tyrone by no means compensated him for his inferior position in the view of the native population. There could only be one ‘O’Neill.’

It is true that neither Hugh nor Turlogh could lay any strong claim to the headship of the clan, which by English usage belonged to Shane, as eldest true son of Conn, and to his sons, Hugh Gavelock and his two younger brothers, held as hostages for the loyalty of their family in Dublin Castle. Hugh Gavelock “of the Fetters,” who was born while his mother was being carried about by Shane in chains, hated Hugh his cousin, whom he looked upon as a usurper.

In 1588 he denounced him to the Council, but before the day arrived the Earl had caused him to be seized and strangled. His enemies later said that the deed was done by his own hand, but Tyrone denied this, though it is certain that there was much difficulty in finding anyone who would lay his hand on the sacred person of an O’Neill.

With the death of Shane’s eldest son and the imprisonment of the younger boys Hugh’s path seemed clearer, but “old Turlogh,” as Hugh O’Neill’s rival came to be called, showed no inclination to die, and continued to play an uncertain game sometimes for, and sometimes against, the Government. He lived till 1595, and during his lifetime it was impossible for Hugh to attain the coveted leadership of his sept, by the free suffrages of his people, though the recognition was of great importance to his projects. At last the clan began to see in Hugh a stronger leader and to transfer their allegiance to him, and he was elected tanist or next in succession in the same year in which Turlogh died.

The actions of Hugh O’Neill were being watched with curious interest by the Government. In person he is described as having a strong frame, though not tall, “able to endure labours, watching, and hard fare; he was industrious, active, valiant, affable, and apt to manage great affairs; of a high, dissembling, subtle, and profound wit. Many deemed him born either for the great good or ill of his country.” This was the testimony of Mountjoy’s secretary, who met O’Neill when he accompanied the Deputy on his expedition to the North. His subtlety was partly learned in the English Court, where intrigue was rife; it carried him through many pitfalls which would have wrecked a weaker or simpler man, and his power of “dissembling” often threw the authorities off the scent.

The Government played off Turlogh and Hugh against each other, and at the battle of Carricklea royalist troops were found fighting on both sides. But on the whole the English supported Hugh, who now and for some time later was the open partisan of the Government. In the Irish Parliament of 1585 he presented his claims to the place and title of Earl of Tyrone, and they were not only admitted, but a recommendation was made to Elizabeth that he should receive back the broad lands forfeited to the Queen after the rebellion of Shane O’Neill.

With Perrot’s letters of commendation he passed over to England, and in 1587 he obtained the Queen’s letters patent for the Earldom of Tyrone, without even the reservation of “the great rent for the Crown,” for which Perrot had stipulated. He agreed, however, to offer no opposition to the erection of forts on the Blackwater for English garrisons, though this was in the heart of his country, and close to his own castle of Dungannon.

For the next seven years the Earl was, at first perhaps sincerely, and later nominally, on the side of the Government and in friendly relations with the Queen. But events were happening in the country that could not but profoundly affect his mind.

In Ulster he saw the beginnings of plantations in the eastern province carried out in a high-handed manner and gradually, as they progressed, threatening to narrow his own dominions. In the South the second Munster rising was seething, ready to burst out on the first hope of outside succour, and tidings of great Spanish armadas once more filled the country. The need of a leader whom the people would accept as their head and as representative of the Catholic cause and who had the influence necessary to unite the interests of the North and South grew urgent, and Tyrone felt that he alone could be such a leader. But the steps that led up to this fateful decision were gradual, and must now be studied.

The year 1588 witnessed the wreck of the Armada on the Irish shores. The storm that brought destruction on the mighty galleons of Spain cast them far and wide around the Irish coast, on the rocks and islands of Mayo, Sligo, and Donegal. According to the Government returns twenty-three Spanish ships were wrecked off Ulster and Connacht and upward of seven thousand men perished there. The new Lord Deputy, FitzWilliam, a covetous man, made a hasty move across Ireland to Connacht to try to secure for himself the treasure said to have been cast ashore from the wrecked vessels. On the way he is said to have captured nearly a thousand Spaniards, but he captured little else, for most of the spoils had fallen into the hands of the natives. All he could do was to wreak his disappointment on the Irish chiefs who had shown humanity to the miserable Spaniards who had been thrown up on the coast in such dire distress, and to order the execution of all Spaniards taken alive, an order which was accomplished without any discrimination of the quality or rank of the prisoners.

Bingham, reporting the losses in his province of Connacht, says that twelve ships were cast on his shores alone, besides others on the Out Isles, “the men of which ships did perish all in the sea, save the number of 1100 or upward, which we put to the sword; amongst which there were divers gentlemen of quality and service.”

It was, perhaps, hardly to be expected that any mercy should be shown to the men the expectation of whose descent on the coasts had been the terror of England for the last five years, and whose destruction was the removal of a national nightmare; but the seizure of Sir John O’Doherty and Sir Owen MacTooley, two lords well affected to the English, on the suspicion that they had taken treasure from the Spaniards, has no excuse. Old Sir Owen was released when Sir William Russell succeeded FitzWilliam as Deputy, but he died shortly after; O’Doherty, a peaceable and cultivated gentleman, was held for two years in confinement, and only received his release on payment of a fine. Treatment of this sort did not tend to strengthen the loyalty of the Northern lords at a moment when such loyalty was most to be desired.

An interesting account remains of the experiences of a Spanish captain, Don Francisco de Cuellar, on the north-west coast of Connacht, one of the most lonely and wildest parts of the country. His ship of twenty-four guns, the Don Pedro, was completely wrecked on a rock ever since known as the Spaniards Rock (Carraig-na-Spanaigh), on the north of Co. Sligo. The Deputy, riding along the strand on his way from Sligo to Ballyshannon, saw strewn upon the shore “as great a store of timber of wrecked ships, as would have built four of the greatest ships he ever saw … and such masts, for bigness and length, as in his knowledge, he never saw any two that could make the like,” and the people of the country told him of twelve or thirteen thousand dead bodies that had been cast up from the wrecked galleons on that coast alone.[5]

Captain de Cuellar, who escaped from the wreck on a piece of boarding and was flung with a few followers, “wounded, half naked, and starving,” on the beach, made his way with difficulty to the castle of Rossclogher, a strong fortress built on a foundation of heavy stones laid in the bed of Lough Melvin and belonging to the chief of Dartry, MacClancy, a “savage gentleman, a very brave soldier, and a great enemy of the Queen of England.”

His ‘town’ was formed of a cluster of primitive huts, which lay on the edge of the lake opposite his castle and surrounded by mountains; here his followers, large-limbed, handsome, active men, clad in rough frieze jackets and tight trousers under the broad shawl or mantle, and eating oat-bread and buttermilk, lived under the eye of their chief, ready at any moment to obey the call to arms, especially against the English garrison planted just outside their territory.

The Spaniards finally made their way “by mountainous and desolate places” round the wild northern coast to Dunluce, everywhere hearing tidings of the losses of their country’s ships. At Dunluce two great vessels had perished, one being the Rata, which carried the young nobles of the highest rank who had volunteered to serve in the Armada. The terrible hurricanes raging round the coast drove back on the rocks all who attempted to make a fresh start, and of the whole of the army only a body of six hundred men, wandering about on the North Donegal coast, who surrendered to Captains Richard and Henry Hovenden, when exhausted by want and lack of food, seem to have been saved. Captain de Cuellar and his small band were sent by Sir James MacDonnell of Dunluce to solicit the help of James VI in Scotland.[6]