Grattan’s Parliament (2)

A question even more important to Ireland than the commercial one stimulated the determination to reject the propositions. From time to time the ominous word “Union” had been heard in the discussions of statesmen and mentioned in their correspondence; even in letters of ministers like Rockingham which dealt with legislative independence, words of ambiguous meaning had been dropped, and some passages in Pitt’s commercial speeches could hardly have any other interpretation. Phrases like “the fundamental principle and the only one on which the plan can be justified … in that for the future the two countries will be to the most essential purposes united,” were watched and repeated with a natural apprehension.

Another matter forced the question to the front. In the autumn of 1788 the King’s mind gave way, and the question of the regency came under discussion in both Parliaments. In England it was disputed whether or not the Prince of Wales should be appointed Regent or had an inherent right to the position. The question became a party matter between Pitt and Fox, and their dissensions were transferred to Dublin, accompanied by liberal offers of place and payment to those who would sell their influence.

The Irish Members seem to have thought it a fair opportunity to assert their right to an independent opinion, and without waiting for the English Parliament to act they moved an address to the Prince in both Houses, praying him to accept the Regency of Ireland “during the continuation of his Majesty’s present indisposition and no longer … under the style and title of Prince Regent of Ireland.”

The Viceroy having refused to transmit their petition, they appointed a deputation to wait on the Prince and present the address. The speedy restoration of the King to health and the good sense of the Prince averted further difficulties; the Members returned with a feeling that the Irish legislature had been premature but that their reception had been kindly.

Into the numerous subtle questions of constitutional practice involved by the regency question it is unnecessary to enter here; party leaders wished to snatch from the position advantages each for his own side. That the Irish Members exceeded their constitutional powers seems clear; they used the occasion as an opportunity to enforce their claim to act independently of any decision come to in England, and fought out this claim with excited feeling.

The fact that to the Irish the person of the Sovereign was the sole acknowledged link between the two kingdoms made the matter of the regency one of special importance to Ireland, and the traditional loyalty of the Irish gentry was shocked at the proposals that were being made in England to limit the powers of the Regent or to assert that any other but the Prince of Wales was eligible to occupy that office.

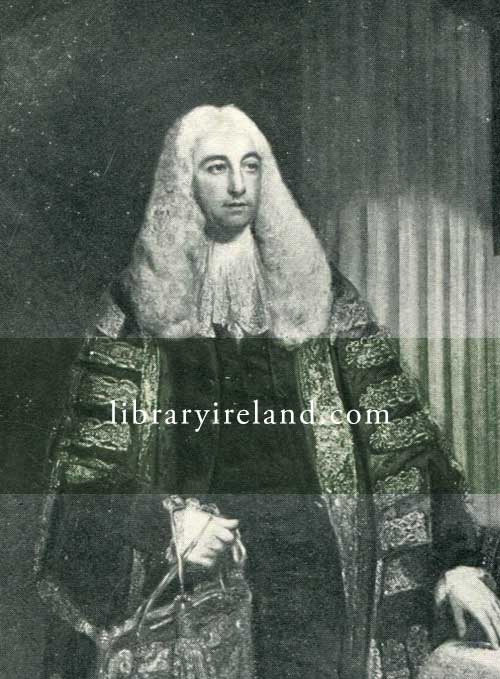

In this discussion a leading part on the Government side was taken by Fitzgibbon, who had in 1783 been appointed Attorney-General,[4] and who later, as Lord Clare, was to become the leading figure in Ireland in the carrying of the Union. Fitzgibbon was the second son of a merchant in Dublin who had been educated as a priest, but who “verted” and became a barrister and made a large fortune in that profession. The son had been educated as a Dublin University man at the same time as Grattan, Foster, and Robert Day. Grattan at this time liked him and spoke of him as “good-humoured and sensible, improving much upon intimacy.”

It is perhaps the best point in a strange character that Fitzgibbon seems to have formed a high opinion of Grattan, “whom,” he says, in a speech in 1785, “I am proud to call my most worthy and honourable friend; the man to whom this country owes more than, perhaps, any state ever owed to any individual; the man whose wisdom and virtue directed the happy circumstances of these times and the spirit of Irishmen to make us a nation.”

The fact that he could appreciate Grattan’s honesty of purpose might predispose us to think Fitzgibbon honest; but his acts show him to have been willing to barter his principles and ruthlessly to crush his friends when the incitements of promotion and place allured him to oppose them. Thus the man who did most to force the Union upon the people he called his nation, had exclaimed in 1785 when the Union was mentioned:

“Who will talk of Union now? If such a thing were proposed to me, I would fling my office in the man’s face.”

Though coming of a Catholic family, he spoke and acted like the incarnation of the Protestant ascendancy party, and until 1793, when he argued against but voted for the franchise for Catholics, he opposed every measure brought forward for their relief. It was chiefly his obstruction that brought to an end Pitt’s intention to carry Catholic emancipation concurrently with the Union.

As a young Parliamentarian, Fitzgibbon had supported Grattan’s independence policy and he had declared in 1782 that “he had always been of opinion that the claim of the British Parliament to make laws for this country is a daring usurpation of the rights of a free people.” “That little man that talked so big would vote for a Union, aye, to-morrow,” was the remark of a prescient friend who listened to his protest against the measure. Dr. Hill, Regius Professor of Medicine in Trinity College, Dublin, says of him:

“I watched Fitzgibbon’s conduct for years, in court and out of it, to friends and foes, to sycophants and expectants; and I came to a clear conclusion that he hated and strove to hurt any man who had any pretensions to honesty and ability.”

Sir Jonah Barrington thought him “the greatest enemy Ireland ever had.”[5] This was the man whose influence was to be almost supreme in Ireland during the years of the rebellion and the Union. That he was a man of ability there is no doubt. Frequently, his judgments of contemporary events and persons were more far-seeing and just than those of his companions in the Ministry, and his speeches, in particular his speech on the passing of the Union, are worthy of careful consideration; but he held in an extreme form the corrupt political notions of his day, and he viewed the prevalent system of governing for the exclusive benefit of “the Protestant garrison” as the only sound method of rule in Ireland. He was the main cause of the withdrawal of Fitzwilliam in 1795, and of the rebellion which followed his recall.[6]

John Fitzgibbon, Earl of Clare

From the painting by Hugh Douglas Hamilton in the National Gallery of Ireland.

Meanwhile, opinion was advancing in various parts of the country, and with particular rapidity in Ulster, on the question of Catholic relief. It was powerful enough to distract attention from the urgency of reform. Recent events had worked in favour of the Catholic claims. “Their uniform peaceable behaviour during a long series of years” had been the acknowledged cause of the removal of disabilities in 1778, and their interest in Irish independence and in the Volunteers had aroused a general feeling that it was unjust that the largest part of the population should be excluded from all participation in the affairs of their own country. The fact that they formed the great majority of the population, which should have been felt to be a reason for special consideration, had been made the pretext for their exclusion from political influence.

Fear and jealousy on the part of the ruling class had brought about this perversion of justice. Even Sir Hercules Langrishe, who was in favour of full religious and educational equality, of throwing open the profession of the law, of removing the limits placed on the number of their apprentices in order to allow them to undertake large industrial businesses, and of permitting intermarriage between Catholics and Protestants, and full and equal land-ownership, hesitated to admit them to the franchise or to seats in Parliament; and, though all other measures of relief were granted by Luke Gardiner’s[7] Bill in 1782 and by Langrishe’s own Bill in 1792, the question of the franchise was still fiercely contested.

The leaders of the patriotic party themselves were deeply divided on the point. Charlemont maintained a conservative attitude of the most unbending character; but led by Grattan and Curran, and supported by an increasing part of the best intellect of the country, the feeling of the Protestants made rapid strides toward a solution of the problem.

The leading part taken by the Presbyterians of Belfast should never be forgotten. They had stood at the head of the demand for legislative independence in 1782 and had won it for Ireland; they now showed themselves equally enlightened and broad-minded in regard to their Catholic fellow-subjects.

In 1792 John O’Neal presented a petition signed by six hundred men of position in Belfast praying for the repeal of all penal and restrictive laws against the Catholics, and asked that Catholics should be placed on the same footing as their Protestant fellow-countrymen. Co. Antrim sent up a similar petition signed by 350 Protestant gentlemen and clergy.

Help came from unexpected quarters. The eccentric Bishop of Derry, who had made himself conspicuous in volunteering and in the struggle for independence, came forward as a vigorous partisan of Catholic relief. He would have admitted Catholics to all offices, including Parliament. He spoke of himself as an example of “the rare consistency of a Protestant bishop, who feels it his duty and has made it his practice to venerate in others that inalienable exercise of private judgment which he and his ancestors claimed for themselves.” His views, energetically announced, made themselves felt in Derry among all classes, and the Presbytery in 1784 had expressed “their perfect approbation of the liberality of his Lordship’s religious sentiments.”

The Protestant Bishop of Killala, Dr. Law, was of the same opinion and denounced the Popery Laws. The powerful advocacy of Burke, which had from his early years been always raised against the monstrosity of the Penal Laws, had found expression in 1782 in his Letter to a Peer in Ireland; in 1792, when the matter was again attracting public attention, he wrote his celebrated Letter to Sir Hercules Langrish.

Nor was Dublin University behindhand. When Grattan, in 1792, discussed in Parliament the admission of Catholics into Trinity College and their right to become professors of non-controversial subjects the motion was supported by the Hon. Denis Browne and other officials of the College, and the question was debated with moderation and good feeling. The Provost, John Hely Hutchinson, went even farther, and supported John Egan’s motion for giving them the franchise.

But, in the towns especially, there was a violent party whose resistance had to be overcome. When Grattan took up the matter he was met by protests from the Dublin Corporation. They said they would have “a Protestant king of Ireland, a Protestant Parliament, a Protestant hierarchy, Protestant electors, and a Protestant Government; the benches of justice, the army and revenue through all their branches and details Protestant; and this system supported by a connexion with the Protestant realm of England.”

Against such a blank wall of public opinion progress had necessarily to be slow. In 1792 resolutions were passed all over the country against giving the elective franchise to Catholics. Petitions went up from the grand juries of Mayo, Sligo, Meath, Cork, and many other counties, largely through the efforts of the boroughmongers. “o give the franchise was to give everything, for everything follows the franchise,” was the general sentiment.

Yet it was to the Protestants, especially of the North, that emancipation was eventually due. The remarkable fact is that the Catholics of the upper classes at this time, both clergy and laity, stood absolutely aloof. They seemed to dislike any sort of agitation and to distrust any appeal.

During the Whiteboy riots of 1779 the Catholic Church had supported all efforts of the Government to put down the rioters; the bishops had sharply denounced the disturbers of the peace and admonished them to return to their homes. A sentence of excommunication was pronounced in the churches of Ossory against “those deluded offenders, scandalous and rotten members of our Holy Church,” by Dr. Troy, then Catholic Bishop of the diocese, and others of the bishops adopted the same attitude. He used the same threat in 1784.[8]

In the early agitation for their own liberties the Catholics remained absolutely quiescent. There was, in fact, no cohesion between the different classes of the Catholic population. The Catholic lords were high Tories, aristocratic and almost obsequiously loyal, hating the middle classes, and resisting all attempts made to induce them to coalesce with them for public purposes.

Charles O’Conor of Belanagare, Co. Roscommon, complains bitterly of the “more than Protestant severity” of the Catholic landowners. He despaired of getting them or the hierarchy to help the Catholic Association to struggle for the rights of their people. “Despair or indifference or unmeaning motives have arrested their hands,” he writes despondingly to Dr. Curry in February 1761. As to the clergy, “Will it be overlooked,” he complains, “that our ecclesiastics to a man have been entirely passive in the prosecution of this measure?”[9]

In the meantime, the Catholics were pouring out addresses of loyalty expressive of their gratitude for the relaxation of the laws already given, and disclaiming, evidently with perfect sincerity, any wish to press further measures other than “the circumstances of the time and the general welfare of the Empire shall render prudent and expedient.” Lord Fingall, the leading Catholic nobleman of Ireland and one who was respected by all classes, writes in 1803:

“The Catholic is ready at this moment to sacrifice his life, his property, everything dear to him, in support of the present constitution. … He wishes no other family on the throne; no other constitution; but certainly he wishes to be admitted, whenever it may be deemed expedient, to a full share in the benefits and blessings of that happy constitution under which we live …”[10]

This was the farthest that he would go.

To us to-day, Catholic devotion to a Constitution from the benefits of which they were rigidly excluded seems a piece of cynicism, particularly when we recall the view taken by George III. on Catholic Emancipation; but it undoubtedly expressed the opinion of the leading Catholic gentry of that day. They had no wish to see the franchise given to the ignorant and easily misled peasantry.

Already in 1784 a number of men of low type were entering the Volunteer Corps, with the immediate effect of loosening its hitherto strict discipline, and causing the rank and file to fall out of control. The “Liberty Corps” enlisted from Lord Meath’s “Liberties,” a district which was a centre of the woollen manufacture, admitted about two hundred of these low-class recruits, with the result that several other corps refused to join with them.

Nevertheless, a remarkable unanimity prevailed among large sections of the people during the early years of the short life of the Irish independent Parliament. For a brief period, Ireland showed that the conception of an Irish nation was one not incapable of being realized. Grattan’s question “whether Ireland shall be an English settlement or an Irish nation” was, indeed, only half answered, for the reins of authority were still held by English hands; but among the bulk of the inhabitants, old Irish and new Irish, there arose a feeling of unity which might well be hailed as the birth of a true national sense hitherto unknown in the country.