Shane's Castle - Story of Belfast

IRELAND is full of ruined abbeys, monasteries, churches and castles, and almost every small town can tell a tale of departed glory. Howth has a history of its own that is unequalled. Malahide Castle has been for eight hundred years inhabited by successive generations of the same family, and the neighbourhood of Dublin overflows with ancient landmarks.

But we must not wander so far from home, for we have as a near neighbour one of the oldest and most beautiful of them all. Shane's Castle,—or, as it was once called, "Eden-duff-carrick,"—has been, since the year 1345, the home of the O'Neills. The Royal house of O'Neill traces its history back to the very beginning of Ireland's story. They were kings of Ulster for one thousand years. Like the branches of a great oak tree that has its roots twined about the very heart of the earth itself, it would be impossible to record a tithe of the events connected with such a people as the O'Neills.

From Donegal to Belfast, all Ulster belonged to them, and they were a terror in Ulster until Queen Elizabeth's time. A clan that could muster 24,500 fighting men was not likely to be easily subdued, and formed a power to be reckoned with. Every schoolboy knows the story of Shane Neill's visit to Queen Elizabeth.

Their ancient stronghold was at Dungannon, their kings were elected in the Primate's Palace in Armagh, and inaugurated with crown and golden shoe on the hill at Tullahogue, until the year 1595.

In an ancient expedition for the conquest of Ireland, the leader of it declared that whoever of his followers first touched the shore should possess the territory. One of them, the founder of the race which supplied Ulster with kings for centuries, coveting the reward and seeing that another boat was likely to reach the land before him, seized an axe and with it cut off his left hand, which he flung on shore, and so was the first to touch it. Hence a red hand became the armorial ensign of the province.

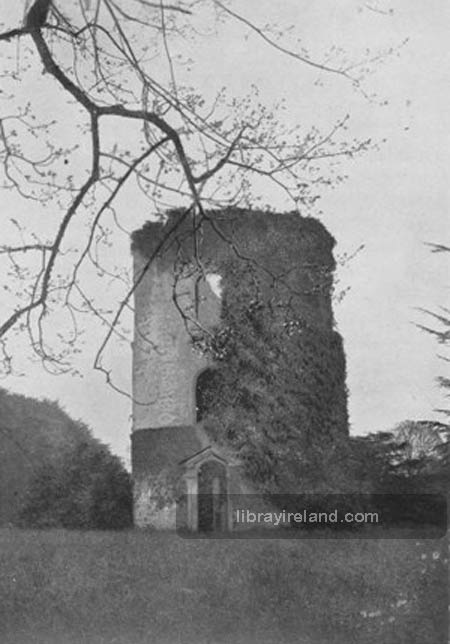

But it is their connection with Shane's Castle we have to do with now. In the year 1230, two sons divided into two separate branches, and the younger settled at Lough Neagh, and this castle was first called Eden-duff-carrick when he built it in 1345. Shane MacBrien O'Neill changed the name to Shane's Castle in the year 1722. He was buried in the small graveyard adjoining, and his vault is still preserved. There is an underground passage from the Castle into the graveyard, and another leading to the edge of the water. These underground passages are of spacious and curious construction. One of them is a great kitchen with a fireplace where immense quantities of food could be prepared. There are stables for horses with an entrance under the terrace, and the water of the Lough came close up to the walls at one time. The most important thing was a spring of good water. There is no doubt that these passages were often used, and were found extremely useful during the rough times of former years. The terrace was built about the year 1800, and twenty pieces of cannon dated 1790 are still there. A large addition to the castle was in course of erection when it was irretrievably destroyed by fire in 1816, which was caused by a rook's nest in the chimney taking fire. The entire buildings were ruined, the fortified esplanade, the cannon and a grand conservatory alone being left.

A great library and some most valuable paintings were lost, and the ruins left show that it must have been a spacious and magnificent building. The present Castle was built on the site of the stable yard. It is a commodious residence, but has no stately dignity or striking beauty to mark its outline.

The demesne extends along the shores of Lough Neagh and covers 2,600 acres of most beautiful scenery. The oak trees are the finest in the north of Ireland, and the gardens are famous for their beauty. There is an old story of one owner who, to pay a fine of £30,000, cut down the timber and paid the debt in oak trees, but they are never missed now, for a hundred years can produce more trees.

Shane O'Neill had a printing-press, an unusual possession in those days, and he had also a chess board formed of the bones of the men of Leinster who were ancient enemies of the race.

Ram's Island on Lough Neagh, six acres in extent, and Bird Island, a smaller place near it, are both very lovely. Ram's Island was once named Inis Island, and a great many years ago it belonged to an old fisherman who obtained possession by prescriptive right. A man called Conway MacNiece bought it from him for one hundred guineas. It then passed into the possession of a man named Whittle, who did much to beautify it. He planted an orchard and made a garden and did a great deal to embellish its natural loveliness. He planted hundreds of rose trees. Whittle, who lived in Glenavy, got the island in exchange for a farm, and some time afterwards Lord O'Neill bought it from him. Ram's Island has been the property of the O'Neill family since then.

Lord O'Neill then built a cottage on the island for occasional residence. The ruins of a round tower and remnant of an old church are still to be seen on the island. Many traditions linger on the shores of Lough Neagh, and the water is said to petrify wood, but a more miraculous quality is ascribed to it. On Midsummer Eve great crowds used to come to bathe in the water to cure all sorts of sickness, and herds of cattle were driven into it for the same purpose.

Such a place as Shane's Castle is full of romance, and when we gaze at the ivy-clad walls of the magnificent ruins, or listen to the music of the river as it hastens to the Lough, we can readily believe that the O'Neill Banshee still appears wandering in the moonlight under the shade of the ancient trees.

Many of the old families in Ireland are believed to have one of these spirits attending them, but in none is there more faith than in the O'Neill's Banshee. She comes to forewarn death by melancholy wailings. "Maoveen"—little Mab—is her name. Vallancy calls her the "angel of death" or separation. Lady Morgan, more poetically, names her "the white lady of sorrow." To doubt the existence of "Maoveen" is never thought of, and indeed all the surroundings favour the idea.

There is a head carved in stone on one of the walls of the ruined Castle, and tradition says that, when it falls, the race will be extinct. It is already loose and tottering, but the race lives on and the head still holds its position. There are few places that live in remembrance like Shane's Castle, few places where superstition is so easily stirred. If we wander under the shadow of the spreading trees, or linger near the little graveyard with its gloomy vault, or stand beside the crumbling walls of the stately towers, we are awed by the thought of all that has come and gone in O'Neill's history since the day the bloody hand first touched the shore. It matters not if we see it in all the green glory of summer sunshine, or in the pale misty moonlight of a still evening, there is no place that can be compared to it. There is, and can be, but one Shane's Castle—it stands alone in a beauty all its own.