Carrickfergus - Story of Belfast

CARRICKFERGUS is about eight miles distant from Belfast. Carrickfergus! The very name carries us away back into the twilight of Irish history. It was once the central point of warfare, standing in the forefront of many a desperate conflict, and it is full of history and romance. Truth and fiction are so interwoven in any place of such antiquity that the task of sifting the facts is not an easy one. We know enough, however, from reliable sources to form a fair idea of the story of one of the oldest towns in Ireland, and many ancient remains of former greatness are still seen which confirm the tale.

Looking at the quiet old town to-day one can scarcely believe that it was once a place of the greatest importance, and the centre of such stirring times, when Belfast was only a small village. The oldest records tell us that an Irish King, Feargus, built the first castle to defend his property three hundred and twenty years before Christ. He crossed to Scotland, and on his return journey he was wrecked on a rock in the bay, called afterwards the Rock of Fergus. His body was found and buried in the adjacent abbey of Monkstown. Another story tells that the same rock was called Carraig-na-Fairge, rock of the sea, from which it is more probable the name Carrickfergus was derived. From that time until a hundred years ago, Carrickfergus suffered almost constant invasion, plunder, bloodshed and burning.

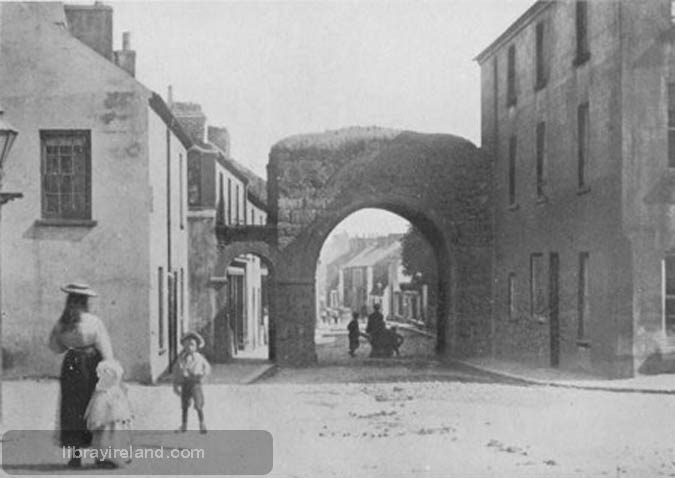

The Castle, the Church and remains of the walls bear silent witness to the oft-told story.

The first wall was built round the city inside a month. It was built of sods and the inhabitants all joined with alacrity to defend the place from their enemies. This wall was afterwards replaced by stone, part of which is still to be seen. It was eighteen feet high, six feet thick and had seven bastions. The corners were of cut yellow stone, freestone, not found in any place in the neighbourhood. A moat safeguarded the landward side, a deep trench and drawbridge the outer side. There were four gates—The Glenarm or Spittal Gate—now the North Gate, the Woodburn or West Gate, the Water Gate and the Finey Gate which had battlements on the top. James I. entered the town by a drawbridge.

The North Gate is still a picturesque memorial of the old days, but we hope the ancient structure may not fulfil the tradition which says: "The North Gate will stand until a wise man becomes a member of the Corporation." A recent resolution was passed which proves that wise men have now a majority on the Corporation, for they have decided to restore the North Gate. Long may it remain as a most interesting object.

It was in the thirteenth century that Carrickfergus was a walled city. It had a Mayor and Guild borough. The country then was alive with game, hare, wild deer and wolf. There was a grand hunting hill above the city.

In October, 1574, the Mayor and the Corporation took very strong measures to put down scolding. Such "skolds" were to be drawn at "sterne of boate from Peare round the Castell," and afterwards exposed in a cage which stood on the quay. History does not relate how many "skolds" survived this drastic treatment long enough to also stand in a cage.

History also carefully avoids stating whether this law was equally enforced for men and women, but we may suppose the law was impartial. The scolding stone was still on the quay until a few years ago.

Some of the old laws were very severe, and we find, in the year 1614, before the judges in the Castle, that a man who stole three cows, worth twenty shillings each, was sentenced to be executed, but one, who struck a woman on the head with a "cudgill" so that she died, was only branded on the left arm and delivered to the Ordinary. They must have been poor specimens of men if they were not worth more than three cows or five shillings worth of a bridle. The sinner who used the "cudgill" was lightly punished, but then it was only a woman—not three cows. A man in Belfast stole a piece of iron worth two shillings, a mantle worth six shillings, and a "chizell" worth eightpence, and he was executed. A woman stole a purse with fifty shillings and she was executed, but a man who beat a woman with a stick until she died, was found "not guilty." Even in those ancient times law does not appear to have been always justice, and it was decidedly in need of being improved, especially from a woman's point of view.

The original charter of the Guild of Carrickfergus is still kept in the Town Hall along with the freeman's roll, the records, and the sword and mace.

The most ancient correct plan of Carrickfergus is dated 1550. In the year 1775, a great storm swept over Carrickfergus, which was accompanied with most violent thunder. The country people said it was a battle between the Scotch and Irish fairies, but no one ever knew which side was victorious.

A stately ceremony was kept up until 1739, in which public proclamations were read at each gate, beginning at the castle. Each man who followed the Mayor rode on horseback with his sword drawn. Afterwards the swords were sheathed when they went to a great banquet given by the Mayor.

One very pleasant memory lingers about the ancient city. There was more charity shown to the poor in Carrickfergus than in any other place in Ireland. No hospital was required, and several of the inhabitants left money to build almshouses for the poor, and also large sums for endowment. This is a happy record for any town to possess.

It is round the Castle that ancient history lingers. The present building was erected by De Courci about the year 1178. It is the only existing edifice in the kingdom which exhibits the old Norman military stronghold, and it is justly considered one of the noblest fortresses of that time now left in Ireland.

It stands on a rocky peninsula thirty feet high, washed on three sides by the sea. Viewed from any point, it presents a most picturesque appearance with its massive walls surmounted with cannon, its ancient gateway with flanking towers and portcullis. One tower is still known as the "Lion's Den," with vaults underneath. The ancient custom is still kept up, and the Mayor of the town is sworn into office in the Castle yard.

The keep is ninety feet high with walls nine feet thick. It is ascended by a winding staircase with loopholes for light and air. It is five storeys high and the lower part is used as a magazine. On the third storey, a room is still named "Fergus' Dining-room"; it is forty feet long, thirty-eight wide and twenty-six feet high, and is a noble apartment.

One inestimable boon was a well inside the building with a never-failing supply of good spring water.

Conn O'Neill was imprisoned in the Castle in the year 1606. I think it was of Conn O'Neill the story was told that some friend sent him a large loaf of bread one day, with a strong fine rope concealed inside, and with it he was able to drop over the prison wall. He made his escape, but returned some time after and was again taken prisoner, when all his vast estates were confiscated. Queen Elizabeth made an order that the Governor of Carrickfergus Castle must always be an Englishman. It was a position more renowned for honour than wealth, for the salary was only £40 a year. We must not linger on the Castle, but touch lightly on the Church. St. Nicholas' Church is built upon the site of a Franciscan monastery. Sir Samuel Ferguson tells in thrilling language of how Corby MacGilmore took refuge at the altar of the old monastery and met with a cruel death even in sanctuary. He had sacked forty monasteries, and sent the monks out to beg their bread, homeless and penniless. He brought back the sacred vessels to lay at the altar, but even the tardy restoration did not save him from his pursuers. There is a subterranean passage under the altar which once led to the ancient monastery, and it can still be traced.

There are some very old painted windows and one transept is filled with monuments of the Donegall family, curious kneeling figures, and the old banners hung from the roof until quite recently. There is a figure of Sir Arthur Moyle on his knees, without any hands, as he lost both hands in Spain when fighting against the Moors. Lord Donegall built a fine mansion on the site of another monastery which was suppressed in the year 1610. The gaol and courthouse now stand upon part of the ground which formerly belonged to the noble house of Joymount. Lord Donegall had spacious gardens round his residence at Joymount. The gaol and courthouse figure largely in history. It was a ghastly custom to spike the heads of the enemies over the gateway, and to allow the blackened heads to be exhibited in such cruel fashion. O'Hagan's head was there so long than an eagle picked the eyes out, and a wren built its nest inside the empty skull, a strange home in which to bring up its family. In the year 1408, there were forty ecclesiastical edifices round about Carrickfergus. A famous priory at Woodburn was called "The Palace" in the year 1326. Long before then, a nunnery had been established at Glynn by Darerca, St. Patrick's sister. There were a great many others, which have been altogether lost sight of. There was a hospital for lepers called St. Bridget's outside the Spittal Gate, and another called Bridewell. The lands adjoining are still called the Spittal Parks. Rumour states that St. Patrick blessed a well and endowed it with miraculous powers of healing. Rumour makes many statements about our patron saint, but in any case St. Patrick's well still exists.

Romance tells us many tales about the unfortunate Edward Bruce who was king for such a brief period, and who was in Carrickfergus in the year 1315. King Robert Bruce of Bannockburn besieged the city of Carrickfergus for twelve months, and he lived there for some time. Then the two brothers left with an army of twenty thousand men, but utter devastation followed, and their later history vibrates with romance and eventful incidents. The end was a sorrowful one. Robert returned to Scotland, Edward was killed in a battle near Dundalk, his head, along with Brian O'Neill's, was salted, and both were sent to King Edward II. at London. A ghastly present for royalty to receive!

The town has a Scotch quarter where the Scotch fishermen lived. A curious custom prevailed among them, that married women never took their husband's name, but retained their own maiden name. The Irish quarter was once called the west suburb. An old signboard used to hang out over a doorway inscribed with this quaint legend,

My ale is good, my measure just

I keep no clerk, and give no trust.

Surely a good sound principle to do business on.

Cairns, raths and ancient remains abound all round Carrickfergus, which will well repay a visit.

A curious relic of the old times remained until the nineteenth century. The "Three Sisters" formed a landmark on the low-lying ground bordering the seashore, and the wooden gibbets where malefactors were hanged, were ghastly objects. The last time they were used, three men were hanged. Seven were sometimes hung at one time, and the tall black crosses stood as a silent warning to evil-doers. It was a place to hasten past in the falling dusk, and no one ever cared to linger on that desolate dreary stretch of shore. Though the gruesome crosses have disappeared long since, the place is still an uninviting waste of marshy ground.