Atlas and Cyclopedia of Ireland - Introduction

MR. JOHN MITCHEL justly remarks, in one of his historical works, that the greatest conquest England ever made was to gain the ear of the world.

In the case of Ireland especially, she has for centuries possessed not only its soil, but the advantage of telling the story of its people from her own viewpoint, while preventing them from making themselves heard in their own behalf.

Down almost to within the memory of living men, education, even in its most rudimentary form, was a felony in Ireland, on the correct principle that the most effective method of subjugating and despoiling a people is to keep them in enforced ignorance.

“In that black time of law wrought crime, of stifling woe and thrall,

There stood supreme one foul device, one engine worse than all:

Him whom they wished to keep a slave, they sought to make a brute—

They banned the light of heaven—they bade instruction's voice be mute.

God's second priest—the Teacher—sent to feed men's minds with lore—

They marked a price upon his head, as on the priest's before.

For, well they knew that never, face to face beneath the sky,

Could Tyranny and Knowledge meet, but one of them should die.

That fettered slaves will link their might until their murmurs grow

To that imperious thunder-peal which despots quail to know;

That men who learn will learn their strength—the weakness of their lords—

Till all the bonds that gird them round are snapt like Samson's cords.

This well they knew, and called the power of ignorance to aid:

So might, they deemed, an abject race of soulless serfs be made—

When Irish memories, hopes, and thoughts, were withered, branch and stem,

A race of abject, soulless serfs, to hew and draw for them.”

In all countries the national history occupies a primal place in their schools and public institutions of learning, but Ireland is an exception.

Irish history has never occupied in modern times in Irish universities, or the so-called Queen's Colleges, the honorable position which every other country in the world but Ireland assigns to the cultivation of its peculiar past.

In schools established under the English government for the professed benefit of the people of Ireland it has been systematically ignored and suppressed.

A few years ago a member of the Queen's University—the latest product of English education in Ireland—had the temerity to deliver a lecture on Irish history before the students of Queen's College, Belfast.

Had the lecturer not ceased to be a student of the University, he would have been expelled for his profanity in introducing the name of Ireland within the walls of a college paid for by the Irish people, and dedicated to the united so-called sanctities of loyalty and nonsectarianism.

With a vigor more violent than argumentative, he was attacked inside the university, and out of it, for having dared to speak of the country of Burke and Sheridan, of Grattan and O'Connell, in the presence of an Irish audience.

He had even the honor of being made the subject of a “question,” in the House of Commons, and of being gravely censured, by some ostensibly solemn members of Parliament, as “a person of seditious tendencies.”

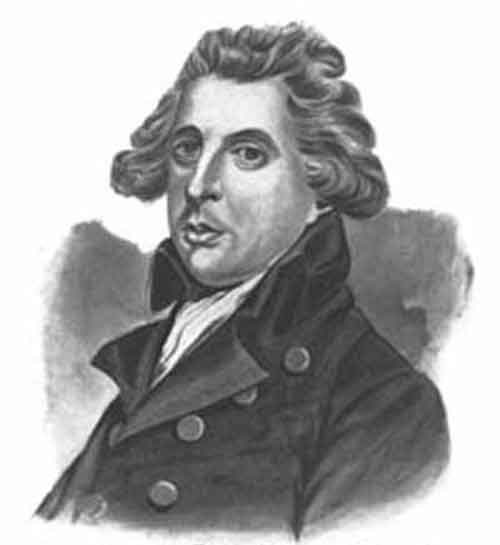

Portrait of Richard Brinsley Sheridan

When the present system of national schools was established in Ireland, it was with the professed purpose of weaning the youth of the country from Irish ideas and aspirations.

All reference to Irish history, literature, and national thought was rigorously eliminated, while the excellencies of the British constitution, and the benefits of British rule were set forth in diversified profusion.

It was fondly hoped that the seeds of loyalty to British rule might thus be implanted, and Ireland be converted into a West Britain. But the attempt was doomed to ignominious failure.

Once place the weapon of knowledge in the hand of youth, and the possessor when grown to manhood will wield it as he I wills. So it has been in Ireland.

In no country is national literature more generously patronized, and liberally diffused.

For ages the spirit of nationality was sustained and transmitted by the wandering bards, the traditions of the clans and families, and the legends and associations that cling, like ivy round a ruin, to every spot of the storied island.

But to the exiled Irish, and their descendants, even such channels and reminders of the history of their fatherland were denied.

Compelled to combat for an existence among strangers, under new and adverse conditions, they had little time or opportunity to devote to the memories or glories of the past.

Yet with a marvelous tenacity they carried with them, retained and transmitted to their children, the inheritance of their ancestors, and to this, in a great measure, may be attributed the status and moral solidarity which the Irish race occupies throughout the world to-day.

For, as Edmund Burke profoundly remarks, a man who is not proud of his ancestry will never leave after him anything for which his posterity may be proud of him.

It is none of our purpose in these brief remarks to advert to the reasons why the Irish and those of Irish descent, especially in America, should be skilled in the history of their race.

Here we are forming a great world-power, evolutionizing a new nationality, and to that nationality, combined of the best elements of Europe, the Irish have contributed, perhaps, the most essential part.

A clamorous minority, indeed, chatter about Anglo-Saxonism, at once a misnomer and absurdity; but the cold figures of the statistics of emigration show that Europe, not England, is the mother country of America, and that to the building of our nationhood Ireland has contributed the greatest share.

These, and kindred facts, are systematically ignored by English writers, and their American imitators, but they no longer dare to dispute them.

A new school of history has been inaugurated, founded on modern scientific historical research; and the record of Ireland, as a civilizer, in the days when Europe, after the break-up of the Roman Empire, was a congeries of bloody factions and races, is now not only recognized but proclaimed by all modern authorities.

As we live in a busy age and country, however, we must adapt ourselves to our requirements and environment; and hence the publishers of the present work have placed within the reach of all Irish-American readers, and sympathizers of oppressed peoples, the most complete, condensed and lucid work on Ireland that has ever been published.

It is an epitome of Ireland, in all her phases, a panoramic view of the ancestral island, which can be appeciated equally by the learned or unlearned, and read and scanned by all readers with pleasure and instruction.

Ireland—geographical and topographical, picturesque, and historic, with her ancient ruins looking down on us with prehistoric venerableness, her antiquities, defying the acutest modern research, her churches, abbeys and monasteries telling in their eloquent remains “the power and faith of old,” all are here presented in the most authentic form and in the best style of modern art.

No expense has been spared in presenting in the most engaging form the Ireland of the Past and the Present to the reader; and at a price that will bring it within the reach of all.

It is needless to advert to the beauties of Irish scenery—which are unsurpassed—or the reminiscences that meet the tourist at every turn, or the manifold attractions that Ireland presents to all in her varying phases, changeful as her skies, and beauteous as her fields, and inspiring as the story that surrounds her.

To those who have been born in the Emerald Isle this work will be of personal interest, containing, as it does, maps of the thirty-two counties of Ireland; to those who have never visited its shores, its scenes of picturesque loveliness, which excite the admiration of every traveler, will be an incentive to see them in reality, when opportunity allows; while those to whom higher aspirations appeal will turn to the lessons which the pages of this work present to them, and, in reading the record of their ancestors, will realize the meaning of the poet:

“They left us a treasure of fit and wrath,

A spur to our cold blood set,

And we'll tread that path, with a spirit that hath

Assurance of victory yet.”