Coleraine - Sketches of Olden Days in Northern Ireland

From Sketches of Olden Days in Northern Ireland by Rev. Hugh Forde

« Rathlin Island | Contents | Derry »

The county now known as Londonderry was in early days known as the county of Coleraine. It was the territory of the O’Cahans, and extended from the Foyle to the Bann. The ancient possession of the O’Cahan family was granted by O’Neill, and was meted out to their chief in the following whimsical manner. O’Neill, in return for important services, granted to O’Cahan as far as his brown horse could run in a day, and also the fisheries of the Bann at Coleraine. Accordingly, starting from Burn Follagh, in the parish of Comber, he rode eastward to the Bann, which was henceforth to constitute his boundary in that direction. The power and authority of the family entitled them to the great distinction of holding the shoe over the head of O’Neill upon the day of his inauguration, the ceremony of which is thus recorded by Camden: “The O’Cahan was the greatest of the Uraights who held of the O’Neills, and being of the greatest authority in these parts he had the honour of holding the shoe over the head of the O’Neill, when chosen according to the rude ceremony then practised upon some high hill in the open air.”

When Sir John Perrott, the Lord Deputy, formed seven counties of Ulster in 1586, the territory of Tyrone was broken up, and the northern part, called O’Cahan’s country, became the county of Coleraine. The residence of the supreme chief was near Limavady, situated upon a high crag nearly 100 feet above the river, and adjacent to the cascade called Limavady or the Dog’s Leap, in the valley of the Roe. The castle is now erased from the face of the country, but its site, and the rath or fort by which it was defended on the land side, may still be traced. The last of the O’Cahans was implicated in the Tyrone rebellion, and his estates forfeited. He was thrown into prison, and afterwards banished and his castle demolished. It was the wife of this O’Cahan that was visited by the Duchess of Buckingham, wife to the Earl of Antrim, her second husband. She had raised a levy of 1,000 men on the Antrim estates in aid of Charles I., and by order of the Deputy, Lord Westmeath, marched them to Limavady. Curiosity induced her to visit the wife of O’Cahan. The old lady continued to live in the ruined home of the family; she had kindled a fire of branches to keep off the rigours of the season within the roofless walls; the windows were stuffed with straw; and Lady O’Cahan herself was found by her noble visitor sitting on the damp ground in the smoke, wrapped in blankets, an affecting illustration of the ruined fortunes of her ancient and noble house. Her only son was sent to college by order of the King, but no trace has been found of him nor of his subsequent history. This county was settled in 1618-19.

From a paper printed in 1608, and given in the appendix of Sampson’s Survey, we take the following curious and interesting particulars: The undertakers of the several proportions should be of three sorts—1, English or Scottish, who were to plant their portions with inland Scots; 2, servitors in the Kingdom of Ireland, who may take mere Irish or English or inland Scottish tenants; 3, natives of Ireland, who are to be made freeholders. The portions were to be distributed by lot. The town of Coleraine, which is now the second in the county of Derry, formerly ranked as a city. According to Harris’s “Hibernica,” and Pynar’s Survey in 1618, “The county of Coleraine, otherwise called O’Cahan’s county, was divided into 547 ballyboes, each ballyboe consisting of 60 acres; in all 34,187 acres.” The town is a place of ancient note; its original name, according to Dr. Reeves in his “Antiquities of Down and Connor,” was “Cuilrathain” (the ferny corner).

For this etymology there is “The Tripartite Life of St. Patrick,” which tells us that St. Patrick, having arrived in the neighbourhood, was hospitably entertained, and a piece of ground on the northern side of the Bann offered him whereon to build a church, in a spot overgrown with ferns. Bishop Carbreus, later on, chose this spot for his abode, from which circumstance it was ever afterwards called “Cuil Rathen” (the ferny retirement). Others derive the name from “Cuil Rath Ean” (the fort at the bend of the river), a much more likely derivation. It was the head of an ancient Bishopric. St. Columba visited Conallus, Bishop of Culerathen, by whom, as well as by the people, he was received with profound respect. But whether it fell into decay by slow degrees, or was destroyed by the Danes, it was of little note until it was again raised to the rank of a city by Sir John Perrott, the Lord Deputy, who laid it out on somewhat the same plan as Londonderry, with a large square in the centre of the town called the Diamond or public square.

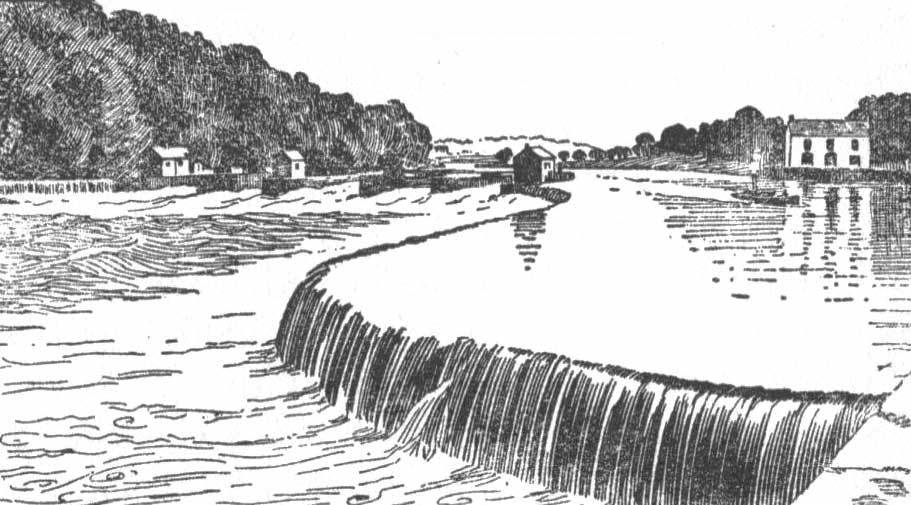

The Salmon Leap, Coleraine

In the vicinity of the town there was a very fine old fort called Mount Sandall, situated on a lofty eminence overhanging the river Bann, nearly over the Salmon Leap. This is generally supposed to have been the site of the great castle built by De Courcy in the year 1197, as mentioned by the Four Masters, and which was granted in 1215 by King John along with the Castle Coulrath (Coleraine) to Thomas de Galweya. Coming down to later times, it was the flight of the Earls of Tyrone and Tyrconnell from Lough Swilly, on the 14th September, 1607, that opened up the way for the great transformation called the “Plantation of Ulster.” The province, alas ! at this time was a wasted wilderness; it could not be otherwise after so many years of war and desolation. At a meeting of the Privy Council held in London at the close of 1612, the Charter was duly prepared, and delivered two years after the city of London had committed itself to the undertaking of the Plantation. Two commissioners, Alderman Smithes and Mr. Springham, were sent to Ulster to inquire into the state of the Plantation and correct abuses. Their report, received in London in November, 1613, was not complimentary to those charged with the work of building. Derry and Coleraine were the only places that received the first attention of the city’s agents. Their report of Coleraine is of interest for the light it throws on the infant settlement—“The chiefest street was unpaved, and almost impassable; several houses were not plastered, and lying open they naturally had not attracted tenants; a general storehouse allowed the rain to pour through so shamefully that the contents were spoiled, firkins of butter decayed, cheese rotted, grievous to behold; nails sent from Derry in open baskets, and therefore rusty. Other houses were tenantless because of the high rates charged. The church, though it had a good attendance of worshippers, showed signs of neglect, and was unplastered. Its interior was described as ‘fowle’ and unhandsome, and the supply of pews scanty.” A contrast indeed to the stately church of to-day, erected through the zeal and untiring energy of Bishop O’Hara, who spent the evening of his days within view of the noble edifice which owes its existence to his pious zeal.

Three years later, in October, 1616, a more cheerful report was given of the progress of Coleraine. It had then, says the report, “ramparts made of earth and sods, along which ran a ditch filled, or soon to be filled, with water. There were also palisades from both sides of the fortifications made into the river, and two drawbridges done by our direction.” Town planning also occupied the attention of the visitors. They suggested another row of houses answerable to the other in High Street, and said, “ we wish them to be built of stone, so as to be defensible against the weather. We caused the Mayor to assemble the whole town, when we gave offer to give as many as will build a single house of stone, With three or four rooms, £20, and a lease thereof for 80 years, for a rent of 6s. 8d. per annum. We find there are 116 houses slated, but inhabited by 116 families having made two or three houses into one. Some others that were built of brick begin to decay, and the walls of others are by weather much decayed. We have given orders that the dormers thereof be slated as at Deny, which is as durable as stone. This will make them strong, where before they were of loam and lime, and ready to fall down.” Then, and for long afterwards, the difficulty of entering the Bann from the sea with vessels was a hindrance to the progress of the town, so that Portrush was regarded as the port of Coleraine.

The offer made by the Commissioners in 1616 is worth noting. “The bar is very dangerous. We saw Portrush so rocky and open to the north seas that it is very dangerous; but we made an offer that if the town and country will join together to make a good harbour there, that would be a means to the city to give £200 towards that charge when it would be finished.” In the time of James I. the Lord Deputy, Chichester, obtained a grant of the fisheries of the Bann. Afterwards the Government purchased back the grant in favour of the London Society. The rent paid to the Society was £900 a year. The expenses of management used to vary from £1,000 to £1,500. As to the quantities taken, it is stated that in one year 250 tons of fish were salted, besides what were sold fresh; the least take of any known year was 45 tons. As to prices, in 1757 salmon sold at 1d. a lb.; for many years after at 1½d. a lb.; at the end of the century it rose to 3d.; later still, to 3½d.

The salmon of the Bann have but one season, and must go sometimes thirty or forty miles to find a convenient place for spawning. It may be of interest to notice the price of other provisions at this time. According to the Commissioners’ report, the prices ruling in Ulster in 1616 were as follows: For a cow or bullock, fifteen shillings, or about one halfpenny per lb.; a sheep, sixteen pence or two shillings; a hog, two shillings; barley, elevenpence per bushel; oats, fourpence a bushel. These figures enable us to understand the value of labour when expressed in terms of £ s. d. The wages paid to a plough-holder were six shillings and eightpence a quarter, with meat and drink; for a leader of a plough, five shillings; for a cow-boy for two heifers, one penny per half-year. Maintenance was evidently the chief return for the labourer’s services. A good servant-maid got ten shillings a year; and a labourer’s pay per day, with meat, was twopence. A master-carpenter or mason received sixpence a day, if he had also meat and drink; but if he provided for himself he was allowed twelve pence per day. The price of the largest pair of brogues was only ninepence. No labourers were allowed to wander from one barony to another without a warrant from a justice of the peace, and no servant was to be hired for a shorter period than half-a-year. Such are some of the facts in the early history of Coleraine, as depicted by Mr. Doyle in his “Antiquities of Ireland,” by Mr. Sampson in his Survey, and by Mr. Kernohan in a recent pamphlet. Coleraine has advanced by leaps and bounds since those days, and can now proudly take its stand as one of the leading towns of Ulster. The story of its infant days is not without interest to its residents of to-day.