Overt and Covert Scots Features in Ulster Speech*

G. Brendan Adams

Scots and English are historically two dialects of one original language. At a certain point in their history, however, between the 15th and 17th centuries, they had diverged so far and were each so well established in their respective domains that they could be regarded as two languages, rather like Danish and Norwegian. Thereafter convergence set in again owing to the changed relationships between the two countries and the geographical expansion of English.(1)

In the 17th century, towards the end of the period of greatest divergence, both were brought to Ulster by considerable numbers of native-speakers of each. Both in due time expanded at the expense of Irish, itself considerably influenced by Scottish Gaelic in the northern and eastern parts of Ulster. Then English began to encroach on Scots within Ulster, but the manner in which this happened differed from the position in Scotland.

In Scotland, English in the narrower sense was an imported prestige language which filtered very slowly down the social scale and from the printed word outwards to the spoken word as a language that one might read but would not normally speak, so that eventually what displaced Scots - in so far as it was displaced — was a regional variety of standard English spoken with a Scots accent. Scots remained at first the spoken language of government from the local level upwards, though not the written language of government, which during the 17th century was progressively anglicized, except in so far as those involved allowed the written style gradually to creep into their formal speech. From the 18th century onwards there was a limited revival of Scots for certain types of literary composition alongside the more general use of English as the written language. Until very recently Scots continued only very slowly to encroach on Gaelic round the margins of the Gaelic-speaking area. The recent rapid language-shift, however, has produced the phenomenon of Highland English, that is, near-standard English spoken with a Highland — originally Gaelic-based —accent in most of that area. Above all, however, there was no mass immigration of English-speakers into Scotland.

In Ulster the position was rather different. At first Scots and English both encroached on Irish, though in different areas. The Scots were originally more numerous than the English, perhaps as much as five or six times as numerous. The relative distribution of the two elements varied considerably, and in east Ulster at least the Scots continued to keep up a close connection with Scotland. In some areas the Scots formed the great bulk of the immigrants and in due time their language came to prevail in such areas. Basic examples are those areas delineated by Prof. R. J. Gregg where an Ulster-Scots dialect is still spoken. Elsewhere the Scots and the English were more mixed, with one group or the other predominating and their combined speech encroaching on the Irish-speaking population, who might acquire a mixture of Scots and English features which they then passed on to the next generation. English was not only the language of the printed word. It was also the language of government from the local level upwards since this was confined on denominational grounds to the Anglo-Irish, who were either of English origin or people of the most varied origins who conformed to their standards as far as possible in language, religion and much else. There was indeed some literary use of Scots in the 18th and 19th centuries but it was confined to the central part of east Ulster and to a narrower social milieu than in Scotland. Though this has continued to a very limited extent at dialect level down to the present, there was no conscious association in Ulster with the Scots or Lallans literary revival that took place in Scotland in the first half of this century. The role of Scots in Ulster has thus been less prominent than in Scotland, but it has been widely diffused in the total spread of the English language (in the wider sense) in Ulster.

The principal contribution to the study of Ulster-Scots has been made by Prof. R. J. Gregg in his various works defining the area in which a Scots-type dialect is now spoken in Ulster.(2) Yet from the nature of his work he has been concerned with recording Scots in its purest surviving form, with the result that he has not really examined features of Scots origin that are more widely diffused into areas which on his definition could hardly now be described as Scots-speaking. This is the type of problem that we are concerned to touch on here rather briefly by defining some of the Scots features that one is likely to find in areas no longer reckoned by Gregg as basically Scots-speaking. These features are almost entirely phonological. Scots words exist in plenty, but many have spread far beyond areas where Scots was normally spoken. Others have shrunk in use even within the Ulster-Scots dialect areas. Each word tends to have its own geography. In looking at the phonology, however, no attempt will be made to define the wider Scots areas exactly. This must await transcription, which has already begun, of the results of our Tape-recorded Survey of Hiberno-English Dialects.(3)

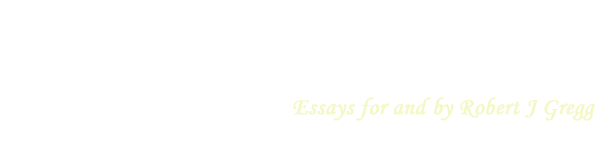

As the argument in this paper depends on matters of pronunciation, it will be helpful to begin by stating how we propose to indicate the different vowel-sounds under discussion. The consonants are hardly involved. Vowels are described by the positions which the tongue takes up in the mouth-space when uttering them. Nine terms are used to explain this: 'front', 'central' and 'back' to denote the placing of the tongue in characteristic positions from near the teeth towards the back of the mouth; 'close', 'half-close', 'half-open' and 'open' to denote relative tongue-height from when the mouth is almost closed with the tongue near the palate to when it is wide open with the tongue lowered and 'spread' and 'rounded' to denote the contour of the lips when they are not neutral. Two more terms, of Hebrew origin, are used for special purposes: the Hebrew letter-name 'yod' denotes the consonantal sound found in e.g. feud, which has the same vowel as food but with 'yod' before it and might be written fyood. The Hebrew vowel-name 'shwa' denotes the indefinite vowel-sound we make when hesitating and not sure what to say next. It is also a common sound in English for all the written vowel-letters when they occur in unstressed syllables.

The mouth-space in which vowel-sounds are formed is of irregular quadrilateral shape, and the relative tongue-positions for each vowel differ from one region to another. In Ulster they are approximately as in chart 1. The code-words used on the chart to denote the vowels we are talking about are of two kinds, with different consonantal frame-works: p-t and f-l. The first group contains vowels that were historically always short, though in Ulster some of them are now often long. There are six of them and they distinguish e.g. the words pɑt, pet, pit, pot, putt, put. Any two of these words are called minimal pairs because their different vowels are the minimal phonetic features used to denote different meanings. Sounds that denote distinctive meanings in a minimal pair are called phonemes. The second group contains vowels that were originally always long or diphthongal. A diphthong is a sound in which the tongue shifts from one position to another. There are eight of these phonemes and they distinguish e.g. the words feel, fɑil, fɑll, foɑl, fool, file, fowl, foil. In all the vowel phonemes on the chart the tongue has a fixed position except those with an arrow leading from their starting-point towards the end-point in the movement of the tongue. These are the diphthongs. Some varieties of English have more diphthongs and fewer simple vowels than we have in Ulster.

When different people have a slightly different pronunciation of a phoneme, these are said to be its diaphonic variants. Some people of course use completely different phonemes in a given word, but that is another matter. An important diaphonic variant of the file-vowel which occurs in certain words only as a covert Scots feature with some speakers in certain areas is shown in square brackets on the chart as the five-vowel. This is a wide diphthong with a much lower and more retracted starting-point than the file-vowel. It is not used by most people in Ulster. In my own pronunciation five has the same phoneme as file. Where the wider retracted sound occurs as a diaphonic variant of this, we might write it as fɑɑive. But for the people who have this sound it is an extra phoneme, because they use the ordinary Ulster file-vowel in other words and minimal pairs can be found which prove that for them the two sounds are separate phonemes. To speakers who have only the one sound, this extra one is a allophonic variant where it occurs.

When a phoneme has slightly different pronunciations owing to the influence of adjacent sounds, especially certain consonants, these variants are said to be its allophones. One important allophone is shown on the charts, in square brackets, in the word feud. This has the fool-vowel, as in food, but because it is preceded by the 'yod' sound, as if written fyood, its tongue-position is more advanced than usual. In fact, it is almost identical with that of the feel-vowel, but has lip-rounding instead of lip-spreading. In the same way the pit- and put-vowels have the same tongue-position, but the latter has lip-rounding whereas the former has not. These are, however, separate phonemes.

With one exception the phonemes in p-t words must be followed by a consonant whereas the phonemes in f-l words can stand finally or before another vowel when another syllable is added. For example, the traditional names of the vowel-letters of the ordinary alphabet all end in a phoneme of the latter type. The exception is the pɑt-vowel, which now stands, lengthened in pronunciation, at the end of a few words of fairly recent origin, such as children's words like pɑ, mɑ, dɑ, bɑ; exclamations and imitatives like ɑh, bɑh, bɑɑ, blɑh, hɑ, yɑh; musical note-names like fɑ, lɑ; contractions like brɑ; and loanwords like fleɑdh 'musical competition' (from Irish), which rhymes with the foregoing. In Ulster these have the pɑt-vowel, whereas some other forms of English use an extra different phoneme, pronounced further back in the mouth, shown on chart 2 as the fɑ-vowel from the name of the musical note.

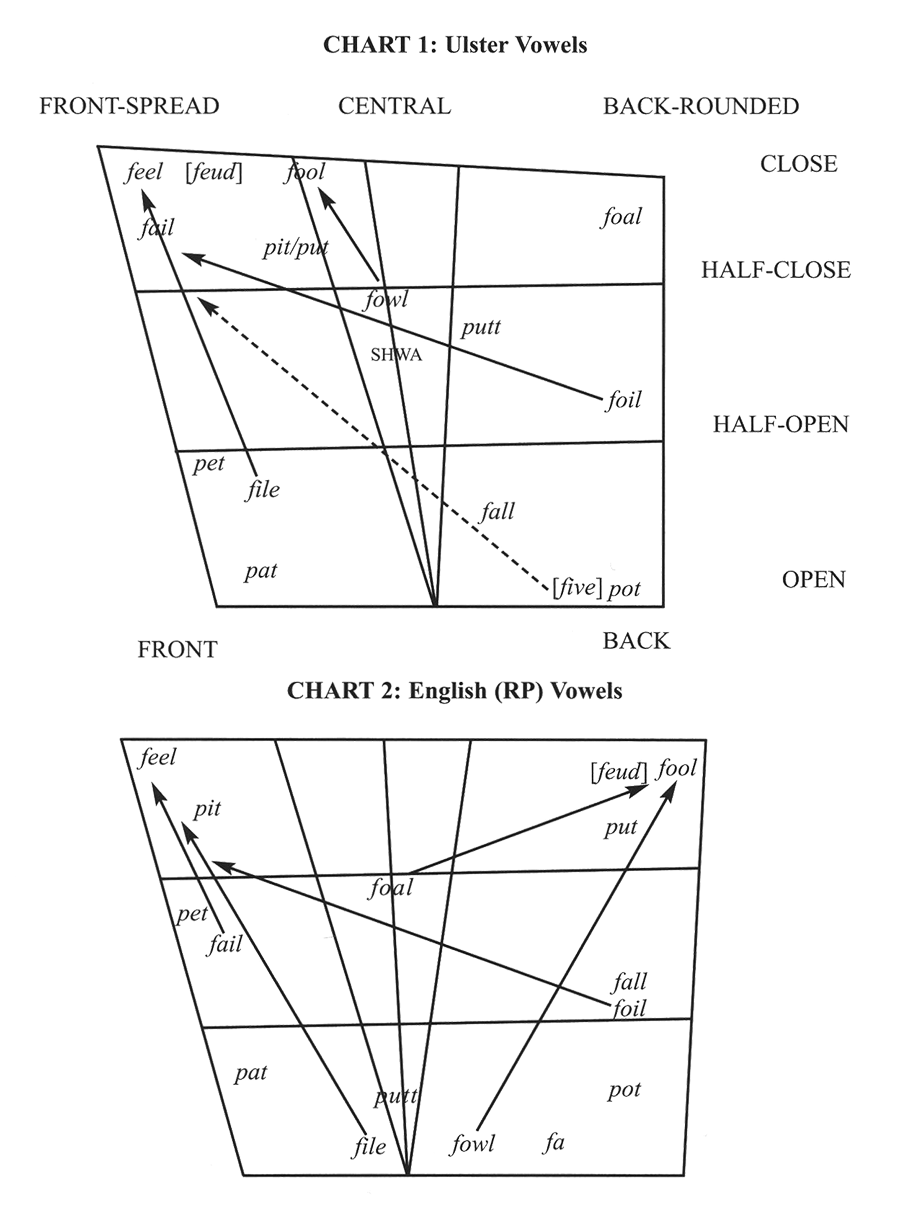

Chart 2 shows, for comparison with the Ulster vowels on Chart 1, the vowel-system of present-day southern English Received Pronunciation (RP). By comparing the two charts one can see how much Ulster English and RP have diverged [from a common ancestor] since the 17th century. The vowels in foil (4) and feel are the only two vowel-phonemes that are virtually the same (not counting frequent shortening of the latter in Ulster), but as it happens these two words are not identical in English and Ulster pronunciation because the Ulster l is a 'clearer' sound than the English l. Among the thousand most frequently used words in the English language 7.5 per cent have the feel-vowel, not counting those where it is modified by a following r, and 0.9 per cent have the foil-vowel. If this group of words is typical of the vocabulary as a whole, it follows that English and Ulster speech have identical vowel sounds in approximately only one-twelfth of all words uttered. In eleven-twelfths of everything uttered the texture of southern English and of Ulster speech differs phonetically, whether the latter is of English or Scots origin.

In defining the Ulster-Scots dialect area, Gregg took fourteen linguistic features as criteria for demarcating Scots from English. These were: one grammatical feature, the use of the Scots negative suffix -nɑe in auxiliary verbs in place of the colloquial English -n't; one consonantal feature, the preservation of the voiceless velar fricative, the so-called egh-sound, which is lost in standard English; and a dozen situations in which the Scots distribution of vowel-phonemes prevails over the English distribution. These may be briefly summarised as follows:

| 1. | use of the feel-vowel, written ei in traditional Scots orthography or with English ee where ei would be confusing, |

| (a) | for the file-vowel in words like dee 'die', ee 'eye', heegh (with audible gh) 'high', breeɑr 'briar' |

| (b) | for the fɑil-vowel in words like bleize 'blaze', mere 'mare' |

| (c) | for the pet-vowel in words like heid 'head', sweit 'sweat', frein 'friend', deid 'dead', weel 'well' (adverb) |

| (d) | for the pit-vowel in words like seik 'sick', leive 'live', gee 'give' |

| (e) | for the fool-, put-, and putt-vowels in certain areas only (east Donegal, mid Ards, east-central Down) in words like bleid 'blood', shein 'shoes', A hɑe loɑst mɑ geed beets ɑbeen the skeel 'I have lost my good boots above the school', as the small boy reported to his mother after taking off his rather too tight new boots to play in the long grass where he then could not find them. |

| 2. | use of the fɑil-vowel, variously written orthographically, |

| (a) | for the foɑl-vowel in words like hɑme 'home', stɑne 'stone', bɑith 'both', rɑip 'rope', tɑe 'toe', mɑir 'more', mɑist 'most', nɑe 'no' (adjective), bɑne 'bone', ɑlɑne 'alone' |

| (b) | for the feel-vowel in words like bɑest 'beast', rɑison 'reason' |

| (c) | for the fɑll-vowel in words like brɑid 'broad', strɑe 'straw' |

| (d) | for the pet-vowel in words like sɑiven 'seven', shɑid 'shed' |

| (e) | for the pɑt- and pit-vowels in hɑe 'have' and wɑe 'with' |

| 3. | use of the pet-vowel |

| (a) | for the pɑt-vowel before ck, g and ng in many words like flex 'flax', leck 'lack', beg 'bag', cleng 'clang'; and in a number of other words such as kemp 'camp', kesk 'cask', this, however, being an east Antrim feature which is not universal throughout the Ulster-Scots-speaking area in many of these words |

| (b) | for the pit-vowel in words such as denner 'dinner', kennelin 'kindling' |

| (c) | for the file-vowel in words like feght (with audible gh) 'fight', ether 'either', nether 'neither' |

| 4. | use of a somewhat centralized variety of the pɑt-vowel, which is always short no matter what consonant follows (unlike some other types of Ulster English, where it may be long before certain consonants); for which reason we designate it specifically as the pɑtt-vowel |

| (a) | for the pit-vowel in words like bɑtt 'bit', bɑdd 'bid' |

| (b) | for the pet-vowel in words like kɑsst 'chest', rɑdd 'red', vɑtch 'vetch', trɑmmel 'tremble' |

| (c) | for the put-vowel in bɑl 'bull' and for the putt-vowel in words like dɑzzen 'dozen', nɑtt 'nut', sɑnn 'son/sun', sɑmmer 'summer', stɑbble 'stubble', rɑnn 'run' |

| (d) | for the file-vowel before nd in words like blɑnn 'blind', fɑnn 'find', and before mb in clɑmm 'climb' |

| 5. | use of an unrounded and lengthened variety of the pot-vowel, for which reason we designate it specifically as the pɑɑt-vowel |

| (a) | for the pɑt-vowel in words like pɑɑt 'pat', pɑɑd 'pad' |

| (b) | for the pot-vowel before labial consonants and ng in words like tɑɑp 'top', rɑɑb 'rob', ɑɑf 'off', lɑɑng 'long', wrɑɑng 'wrong' |

| (c) | for the pet-vowel after w and wr in words like wɑɑl 'well' (noun), wɑɑt 'wet' (adjective) — but weet for the verb 'wet' — whɑɑlp 'whelp', wrɑɑn 'wren', wrɑɑstle 'wrestle' |

| (d) | for the fɑll-vowel in many Ulster-Scots areas in words like wɑɑ 'wall', fɑɑ 'fall', ɑɑ 'all', sɑɑt 'salt', scɑɑd 'tea' (scald), and likewise for the foɑl-vowel in words like blɑɑ 'blow', rɑɑ 'row', crɑɑ 'crow', and for the fool-vowel in words like twɑɑ 'two', whɑɑ 'who', but this is not universal as some areas have the fɑll-vowel in all such words, though not the l that sometimes follows it in the English form, and other areas have a long diphthong consisting of the pɑɑt-vowel moving towards the fɑll-vowel, e.g. fɑɑw 'fall', blɑɑw 'blow'. |

| (e) | for the fɑil-vowel in words like mɑɑk 'make', wɑɑd 'wade', ɑwɑɑ 'away' |

| 6. | use of the fɑll-vowel, without the lowering and unrounding tendency found in some areas, for which reason we designate it specifically as the pɑut-vowel |

| (a) | for the pot-vowel in words like pɑut 'pot', pɑud 'pod', blɑuk 'block' |

| (b) | for the pɑt-vowel in words like tɑussel 'tassel', bɑurɑ 'barrow', and for the pet-vowel in ɑuny 'any' |

| 7. | use of the foɑl-vowel |

| (a) | for the fɑll-vowel (written o before r) in words like shoɑrt 'short', coɑrd 'cord' |

| (b) | for the pot-vowel in words like roɑk 'rock', no 'not' (emphatic), doɑg 'dog' (in some areas only) |

| 8. | use of the fool-vowel or the put-vowel, usually according to the nature of the following consonant |

| (a) | for the fowl-vowel in words like the following, either with the traditional Scots orthography ou or spelt with English oo where ou would be misleading: toun 'town', broun 'brown', hoose 'house', coo 'cow', mooth 'mouth', drooth 'drought' (with loss of gh and change of t to th), doot 'doubt', roon 'round' |

| (b) | for the putt-vowel in some words like roost 'rust', thoom 'thumb', sook 'suck' |

| (c) | for the foɑl-vowel in some words like shoother 'shoulder', cooter 'coulter', heard in the saying he hes ɑ neb on him like ɑ cooter (neb is 'nose') |

| (d) | for the foil-vowel in pousion or poozhon 'poison' and in foozhonless 'tasteless' from the archaic word foison 'plenty' |

| (e) | for the put-vowel with lengthening and loss of final l in words like fou 'full', pou 'pull' |

| 9. | use of the pit-vowel |

| (a) | for the fool-, put- and putt-vowels, except in certain marginal areas (see section 1(e) above), in words like gid 'good', blid 'blood', lim 'loom', giss 'goose', shin 'shoes', A hɑe loɑst mɑ gid bits ɑbin the skil 'I have lost my good boots above the school' (cf. section 1e), riff 'roof' |

| (b) | for various vowels in negative forms of verbs and contractions of prepositions with pronouns such as dinnɑe 'don't', disnɑe 'doesn't', hinnɑe 'haven't', hittɑe 'have to', wit 'with it', fit 'from it' (from fɑe it) |

| 10. | use of the putt-vowel |

| (a) | for the put-vowel in words like putt 'put', cud 'could', wud 'would'; sometimes also for the pot-vowel in dugg 'dog' |

| (b) | for the pit-vowel, especially after w, wh, wr, qu, in words like twust 'twist', whup 'whip', wrust 'wrist', quult (or kwult, to avoid the unusual letter-combination quu) 'quilt', wunter 'winter', bruckle 'brittle' |

| (c) | for the pet-vowel in words like twunty 'twenty', munny 'many', studdy 'steady' |

| (d) | for the fool-, put- or putt-vowels before k, gh and g, in which case it is preceded by 'yod' and written eu in Scots traditional orthography, in words like beuk 'book', heuk 'hook', eneugh (with gh pronounced as the egh-sound) 'enough', likewise teugh 'tough', but when the gh is lost as in peu 'plough' (where the l is also lost) the eu is pronounced with the second element long as in feud. Another word with the same phonology is feuggy 'left-handed'. |

| 11. | use of the file-vowel |

| (a) | for the fɑil-vowel, spelt with ey in traditional Scots orthography or with English ie where this is less ambiguous than ey, mainly when final in words like hey or hie 'hay', pey or pie 'pay', cley or clie 'clay', reyns or rines 'reins', gey 'very', ɑy 'always' |

| (b) | for the foil-vowel in bile 'boil' (noun) |

| (c) | with the back open starting point of the five (fɑɑive)-vowel replacing the ordinary file-vowel pronunciation when final or before r, v, th, z and the verbal ending d in words like pɑɑy 'pie', fɑɑive 'five', sɑɑythe 'scythe', prɑɑize 'prize', tɑɑie 'tie', tɑɑied 'tied' (as opposed to tide with the ordinary file-vowel) |

| 12. | use of the fowl-vowel |

| (a) | for the foɑl-vowel in words like oul 'old', coul 'cold', boul 'bowl', sowl 'soul', houl 'hold', powl 'pole', pownie 'pony', bestou 'bestow', grou 'grow', tou 'tow' (noun) — or growe and towe for the last two on the analogy of knowe 'small hill, knoll', ower 'over', 'too'. To represent this sound orthographically one can reverse the roles of ou and ow of standard spelling. Sometimes for the pot-vowel in dowg 'dog'. |

| (b) | for the fɑll-vowel in thow 'thaw' |

| (c) | for the fool-vowel in such words as yow 'ewe', lowze 'loose' (verb), 'loosen', chow 'chew' |

| (d) | for the feel-vowel in lowp or loup 'leap' |

The factors working for the anglicization of Scots in respect of these features are not quite the same in every case, particularly where the effect of written English on Scots pronunciation is taken into account. English not, and its older Scots equivalent nɑt, do not in either case represent exactly the normal colloquial forms, respectively -n't and -nɑe (or -nɑ in some parts of Scotland). One could therefore go on using the Scots reduction without regard to the written form even when one had abandoned other Scots features, and this is exactly what one finds in many parts of Ulster except in very formal speech. The loss of the egh- sound in standard words, which is in any case preserved throughout Ulster in dialect words of Scots or northern English origin like sheugh 'ditch' and loanwords from Irish like lough would not be induced by the literary spelling, which preserves the gh, though ch is more commonly used in traditional Scots spelling. One could read a Scots pronunciation out of forms like tɑught, weight, right even better than an English pronunciation, particularly if one felt a native urge to distinguish them from their English homonyms tɑut, wɑit, rite, by retaining the original egh-sound. In the case of these two Scots features the force of the most familiar written forms would not count in the process of anglicization by way of producing spelling-pronunciations. This process would depend entirely on the adoption of a different spoken standard in a given grammatical situation or for a given set of words.

With the words in which Scots and English vowel phonemes differed the case was rather different because here there were old established differences in spelling. The use of literary English by persons who spoke Scots, especially the use of the Authorized Version of the Bible from the early 17th century onwards, made Scots-speakers familiar with English forms as reading pronunciations even if they never used them in natural speech. The Scots forms of such words may be called overt Scots forms, and it is precisely these that have in the main been lost in the process of anglicization.

Considered diachronically the Scots forms cited above with different vowel phonemes from their English equivalents can of course be explained historically in terms of the multifarious origins of each standard English vowel phoneme. Considered synchronically, however, these differences, which affect small word-sets and even individual words in different ways, seem to be largely random and unpredictable, apart from the special case of Ulster-Scots pɑɑt, pɑtt, pɑut respectively for Ulster English pɑt, pit, pot — see sections 4(a), 5(a) and 6(a) in the list above — which will be discussed below. The Scots-speaker, wishing to make himself more widely understood, has learnt to make the appropriate English substitution, a process known as code-switching. There has been a long tradition of doing this, supported in part by the written word but also by the close proximity of traditional spoken Ulster English. Sometimes this has led to code-switchings that produce results at variance with standard English, because Ulster English uses dialect forms, mainly of English West Midland origin, that the speaker of Ulster-Scots has falsely assumed to be standard English. An interesting case is provided by the word ewe, which has the feud-allophone of the fool-vowel in standard English. The commonest Scots form is yow (which has the fowl vowel), but the traditional Ulster English dialect form is yoe and there is a long-established convention that when speakers of Ulster-Scots switch to English with outsiders, they use the Ulster English dialect form yoe for this word and not its standard English form.

Again, it sometimes happens that Ulster English and Ulster-Scots occasionally share common features of dialect origin that are untypical of their standard forms. Thus words of the type old, cold have the fowl-vowel in both (though usually with loss of the final d in the Ulster-Scots forms). In the case of Ulster English this is a pronunciation of West Midland origin at variance with the East Midland foɑl-vowel of the standard language. In the case of Ulster-Scots it is an old type of pronunciation, surviving also in some marginal areas of Scotland, at variance with the more general modern Scots form with the fɑll-vowel. In such a case there was no need for code-switching on the part of Scots-speakers because speakers of Ulster English used the same phoneme anyway.

Behind the loss of these distinctive Scots forms then — a process not yet completed in many areas — lies a long period of semi-bilingualism with Scots as the spoken language but English as the written and formal reading language. So far as the vowel phonemes are concerned, the process of code-switching almost invariably takes place when one of the vowel phonemes involved, either on the Scots side or the English but more particularly on both, belongs to the f-l series of long phonemes. Where different Scots and English vowels both belong to the p-t series, there may be hesitation and sometimes even neglect of code-switching. This is most prevalent in the special cases we are about to consider below involving Scots pɑɑt, pɑtt, pɑut for English pɑt, pit, pot respectively. Indeed this confrontation of disparate sounds is specifically an Ulster matter, because of the juxtaposition here of Scots and English, and it does not arise in Scotland, where the linguistic situation is different.

Of the thousand most frequently used words in the language roughly 30 per cent differ in their Scots and English forms, not counting the special differences involving Ulster-Scots pɑɑt/pɑtt/pɑut for Ulster English pɑt/pit/pot that we have just mentioned. This includes words with consonantal differences such as the dropping of final d after l and n and the reduction of medial nd and mb to nn and mm where vowel differences are not involved. Words in which Scots and English differ in their use of vowel phonemes of the f-l series, though not counting the Scots use of the back-open five-variant of the file-vowel, that is, the group where code-switching is most likely to occur, amount to only 13 per cent of the thousand most frequently used words in the language. To these may be added words containing the egh-sound in Scots, where code-switching to the English form almost always entails a change in the vowel phoneme as well as the loss of gh. These amount to 2.1 per cent of the thousand most frequently used words. It follows that Gregg's criteria for distinguishing Scots from English in Ulster amount to a rather slender proportion of the most used vocabulary. We may suspect that as the total vocabulary increases the proportion of words with distinctive features where code-switching always occurs will diminish.

Scots features in the vowel system, however, are not confined to those that have long found expression in the spelling of standard English and of traditional literary Scots, which provides one motivation for code-switching. There are many phonetic differences between the vowel sounds of each which were not felt to be sufficiently great to merit different spellings. In any case such small differences would have been hard to express through the ordinary five-vowel alphabet. In Scotland, where English when it eventually became established is spoken with a Scots accent, this has been of no significance because there are no large blocks of English-speakers interspersed among Scots-speakers, at least in rural areas. But in Ulster the case is different. Here Scots is in geographical and often social confrontation with English, deriving either from primary English sources or from English as a secondary language acquired historically by Irish-speakers. Consequently phonetic differences that do not occur within Scotland between speakers of Scots and speakers of Scotticized English can occur side by side and survive as well-marked features in Ulster. Unlike the older overt differences which form the basis of Scots/English bilingualism, they are accepted as differences of accent which do not prevent comprehension. People do not switch from one to the other, as happens when Scots-speakers switch from the overt Scots forms they would use when talking among themselves to the English forms they would use when talking to outsiders. The variants of these pronunciations which are of Scots origin are what we may call covert Scots forms, and they have persisted even when the overt Scots forms have been lost because they are not subject to code-switching in bilingual situations.

Before discussing these features we must look for a moment at the overall distribution of vowel phonemes within the standard language and then at the variety of English, as distinct from Scots, established in Ulster. Among the thousand most frequently used words in the language some 15 per cent contain vowels modified by syllable-closing r, which we have decided to ignore as not being strictly relevant to the differences between Scots and English in Ulster. Unlike their parent languages in Britain, where r operates quite differently on the preceding vowel, Ulster-Scots and Ulster English both have a reverted resonant r which modifies and usually lengthens the preceding vowel. In Scotland on the other hand a rolled r leaves the preceding vowel completely unmodified. In England, apart from Wessex, Kent, Surrey and the West Midlands, Lancashire and Durham-Northumberland, r is lost; preceding original short vowels have been lengthened and shifted in quality; preceding original long vowels and diphthongs have developed a shwa-glide after them to produce what are called centering diphthongs, that is, those in which the tongue moves from one of the clear vowel positions towards shwa, and in certain cases the latter then alters the quality of the vowel and is itself lost. The Ulster equivalents of all these developments need not concern us here.

In a very small number of words, about 0.5 per cent, the original vowel has normally been reduced to shwa because these little words are of the kind that almost always occur unstressed in the sentence. The distribution of vowel phonemes over the remainder of the most frequently used words — which can probably be taken as fairly representative of the vocabulary as a whole — is as follows:

| p-t series | f-l series | ||

| feel-vowel | 7.5 per cent | ||

| pɑt-vowel | 7.8 per cent | fɑil-vowel | 7.9 per cent |

| pet-vowel | 11.7 per cent | fɑll-vowel | 2.4 per cent |

| pit-vowel | 11.2 per cent | foɑl-vowel | 6.2 per cent |

| pot-vowel | 5.9 per cent | fool-vowel | 4.7 per cent |

| putt-vowel | 6.8 per cent | file-vowel | 7.1 per cent |

| put-vowel | 1.4 per cent | fowl-vowel | 3.0 per cent |

| foil-vowel | 0.9 per cent | ||

| 44.8 per cent | 39.7 per cent | ||

It is noticeable that the front-spread vowels and diphthongs, the sounds heard in pet, pit, fɑil, feel, file, though only five in number, are more heavily weighted than the remaining nine vowel phonemes. The least frequent vowel, the sound heard in foil, does not occur in native Germanic words of Old English and Old Norse origin. It is confined to words of Old French and, much less frequently, Dutch origin. The next most infrequent phoneme, the put-vowel, derives in equal proportion from what were originally allophonic variants of the putt- and fool-vowels. Though it exists as a separate phoneme in some types of Ulster speech (my own, for example), there are others in which its words are divided between these two other larger groups. Of the words containing the pɑt-vowel in Ulster, exactly one third of those most frequently used have the fɑ-vowel in RP. Of the 7.1 per cent of file-vowels, only 5.2 per cent have this vowel (or another substitute) in Ulster-Scots, while the other 1.9 per cent have the extra back-open five-diphthong in its place.

It has already been stated above that the largest group of features used by Gregg to distinguish Scots from English are those involving vowel differences where at least one of the vowels concerned belongs to the f-l series of phonemes, and that these amount to 13 per cent of the most frequently used words. It will now be seen that this is just about one third of the most frequently used words with phonemes from this group. Apart from the special case of the extra five-diphthong, still to be further discussed, and some diaphonic variants of the fɑll-vowel, which are, however, not universal in Ulster-Scots, there are no phonetic variations between the Ulster-Scots and Ulster English versions of phonemes in the f-l series, at least so far as vowel quality is concerned. Whether there are variations in respect of length is a point we have not yet investigated.

Among the thousand most frequently used words in the language those that have code-switching between a Scots and an English vowel where both belong to the p-t series are decidedly less numerous and number only 5.5 per cent or about one eighth of the most frequently used words with phonemes in this group. Moreover, in such words code-switching sometimes fails to take place at all. The writer once knew a north Antrim man who consistently retained the Scots putt-vowel for the English pit-vowel when it occurred after w, wh, wr, qu, though he made the other Scots-to-English code-switches. One often hears other departures from the English-type vowel distribution with vowels from the p-t series in particular words which turn out on closer examination to belong to the Scots-type vowel distribution. Is it the case that people readily enough make code-switches involving vowels from the f-l series because fundamentally these phonemes have the same sound in both the Scots and the English systems in Ulster, so that it is simply a case of reshuffling phonemes that are already native and familiar over a particular set of words? Conversely, is there a certain resistance to doing this with phonemes from the p-t series because the Scots set and the English set are slightly different phonetically and are felt to be not entirely native to the speaker's sound-system? This is a point of linguistic psychology that has not yet been sufficiently investigated. If the Scots and English versions of the p-t series of vowel phonemes persist as separate entities that broadly speaking are not affected by code-switching, then the Scots material in Ulster speech is much more widespread than was envisaged by Gregg and merits further investigation. On the showing of the thousand most frequently used words in the language this element affects just over 43 per cent of the vocabulary, omitting the small group of words that can have the put-vowel, since their status is questionable. On this scale the scope for tracing Scots elements surviving in Ulster speech becomes very much wider.

To turn now to Ulster speech of English origin, as well as being less numerous than the Scots, its speakers came from a greater variety of dialect areas, though one result of their mingling in Ulster has been that many of the more distinctive English dialect features, such as initial z, v and dr in place of s, f and thr among speakers from Wessex, have been obliterated. On the other hand most of them came from areas other than the East Midland dialect area, where standard English arose. A few did indeed come from the London area, from parts of East Anglia and from the Nottingham-Leicester areas, but they were greatly outnumbered by those from western England, mainly from the West Midland dialect area, with a lesser number of speakers of Wessex English from Devon, Somerset and Gloucester. The West Midland people came partly from its northern Lancashire-Cheshire-Derbyshire and south-Yorkshire portion and partly from its southern Warwickshire-Staffordshire-Shropshire portion. Speakers from the area north of the Humber-Wharfe-Ribble line, that is, from the Northern English dialect area, were less numerous, but as their Northern English dialect would have agreed phonologically, if not always phonetically, with Scots, they hardly affect the issue of Scots/English linguistic relationships.

The mainly western origin of Ulster English, however, means that it differed in many points from the East Midland variety out of which standard English has developed. In addition to that there is a chronological factor involved, in that many of the features that now characterize the RP pronunciation of English date only from the 18th century and had not yet developed when western English was transplanted to Ulster. Examples of this are: (1) the loss of r when not followed by a vowel; (2) the falling together of all originally short vowels except ɑ and o as a long neutral shwa-vowel when followed by syllable-closing r; (3) the separation of the long back fɑ-phoneme as in ɑunt and cɑlm from the short front pɑt-phoneme as in ɑnt and cɑm. In Ulster English these four words all have the pɑt-vowel, though it is short in both ɑunt and ɑnt and long in both cɑlm and cɑm because of the nature of the following consonant. In addition to these points Ulster English is a type in which: (1) the file- and fowl-vowels are narrow diphthongs with a central or half-open starting-point instead of wide diphthongs with an open starting-point as in RP; (2) the fɑil- and foɑl-vowels are half-close long vowels (the latter shortened before certain consonants) and not narrow diphthongs as in RP; (3) the fɑll-vowel has not normally fallen together with the for-vowel (with loss of r in the latter case), but is either somewhat centralized in its tongue-position or else much more open and often unrounded; (4) the fool-vowel is much advanced to the close central position, especially when preceded by the yod-sound as in feud, and is often shortened but not necessarily distinguished from the put-vowel; and (5) the velar consonants k and g have a distinctly palatal pronunciation, like ky and gy, before and after the pɑt-vowel. All of these features except the last bring Ulster English nearer to Scots than is the case with most types of speech in present-day England. They are not necessarily of Scots origin, but may be due to independent evolution — or more often lack of evolution — since the 17th century. Yet the two sound systems remain distinct, even apart from those Scots features which we have described as overt. It is mainly in respect of the historical short vowels that this is so.

Notes

* Unpublished typescript on deposit at Ulster Folk and Transport Museum, c. 1967.

(1) Craigie, William, 'Scottish Language' in Chambers' Encyclopedia (Edinburgh, 1950), revised by A. J. Aitken, 1962.

(2) Gregg, Robert J., 'The Scotch-Irish Dialect Boundaries in Ulster' in Wakelin, Martyn (ed.), Patterns in the Folk Speech of the British Isles (London, 1972), 109-139.

(3) For a collection of papers on the Tape Recorded Survey of Hiberno-English, see Barry, Michael (ed.), Aspects of English Dialects in Ireland Vol. 1: Papers Arising from the Tape-Recorded Survey of Hiberno-English Speech (Belfast, 1981).

(4) Sometimes pronounced [ai] in Ulster.