Protection of Crafts in Ancient Ireland

From A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland 1906

« previous page | contents | start of chapter | next chapter »

CHAPTER XX....concluded

6. Protection of Crafts and Social Position of Craftsmen.

Artificers of all kinds held a good position in society and were taken care of by the Brehon Law. Among the higher classes of craftsmen a builder of an oratory or of ships was entitled to the same compensation for any injury inflicted on him in person, honour, or reputation, as the lowest rank of noble; and similar provisions are set forth in the law for craftsmen of a lower grade. Elsewhere it is stated that the artist who made the articles of adornment of precious metals for the person or household of a king was entitled to compensation for injury equal to half the amount payable to the king himself for a like injury.

As illustrating this phase of society we sometimes find people of very high rank engaging in handicrafts. One of St. Patrick's three smiths was Fortchern, son of Laegaire, king of Ireland. But, on the other hand, a king was never allowed to engage in manual labour of any kind (p. 25, supra). Many of the ancient Irish saints were skilled artists. In the time of St. Brigit there was a noted school of metal-workers near her convent, over which presided St. Conleth, first bishop of Kildare, who was himself a most skilful artist. St. Dega of Iniskeen in Louth was a famous artificer. He was chief artist to St. Kieran of Seirkieran, sixth century; and he was a man of many parts, being a caird or brazier, a goba or smith, and besides, a choice scribe. In the Martyrology of Donegal it is stated that "he made 150 bells, 150 crosiers: and also [leather] cases or covers for sixty Gospel Books," i.e. books containing the Four Gospels.

In the household of St. Patrick there were several artists, all of them ecclesiastics, who made church furniture for him. His three smiths were Macecht, who made Patrick's famous bell called 'Sweet-sounding'; Laebhan; and Prince Fortchern, as mentioned above. His three braziers were Assicus, Tairill, and Tasach. In the "Tripartite Life" it is stated that "the holy bishop Assicus was Patrick's coppersmith; and he made altars and quadrangular tables, and quadrangular book-covers in honour of Patrick."

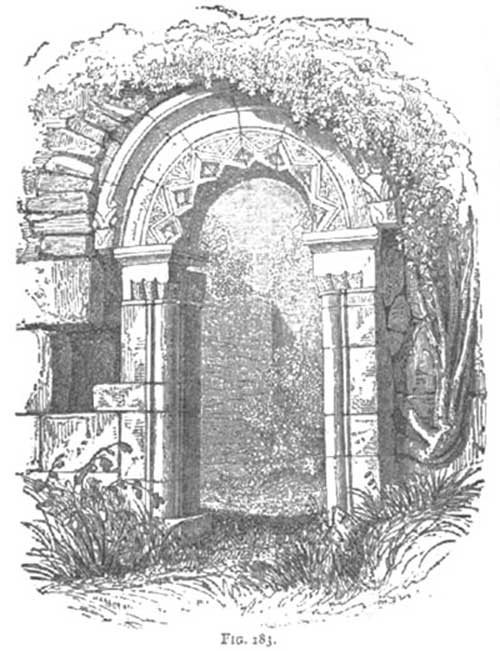

FIG. 183. Doorway of Rahan Church, King's County, dating from middle of eighth century. Specimen of skilled mason-work to illustrate what is said at pp. 451, 452, supra. (From Petrie's Round Towers).

We have already seen how highly scribes and book-illuminators were held in esteem. Nearly all the artists selected by St. Patrick for his household were natives, though there were many foreigners in his train, some of whom he appointed to other functions: a confirmation of what has been already observed, that he found, on his arrival, arts and crafts in an advanced stage of cultivation.

No individual tradesman was permitted to practise till his work had been in the first place examined at a meeting of chiefs and specialty-qualified ollaves, held either at Croghan or at Emain, where a number of craftsmen candidates always presented themselves. But besides this there was another precautionary regulation. In each district there was a head-craftsman of each trade, designated sai-re-cerd [see-re-caird], i.e. 'sage in handicraft.' He presided over all those of his own craft in the district: and a workman who had passed the test of the examiners at Croghan or Emain had further to obtain the approval and sanction of his own head-craftsman before he was permitted to follow his trade in the district. It will be seen from all this that precautions were adopted to secure competency in handicrafts similar to those now adopted in the professions.

Young persons learned trades by apprenticeship, and commonly resided during the term in the houses of their masters. They generally gave a fee: but sometimes they were taught free—or as the law-tract expresses it—"for God's sake." When an apprentice paid a fee, the master was responsible for his misdeeds: otherwise not. The apprentice was bound to do all sorts of menial work—digging, reaping, feeding pigs, &c.—for his master, during apprenticeship.

END OF CHAPTER XX.

« previous page | contents | start of chapter | next chapter »