The Royal Residence of Tara

From A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland 1906

« previous page | contents | start of chapter | next page »

CHAPTER XVI....continued

5. Royal Residences.

Almost all the ancient residences of the over-kings of Ireland, as well as those of the provincial and minor kings, are known at the present day; and in most of them the circular ramparts and mounds are still to be seen, more or less dilapidated after the long lapse of time. As there were many kings of the several grades, and as each was obliged to have three suitable houses (p. 24, above), the royal residences were numerous; of which the most important will be noticed here. In addition to these, several of the great strongholds described at pp. 39 to 42, supra, were royal residences.

Tara.—The remains of Tara stand on the summit and down the sides of a gently-sloping, round, grassy hill, rising 500 feet over the sea, or about 200 over the surrounding plain, situated six miles south-east of Navan, in Meath, and two miles from the Midland Railway station of Kilmessan. It was in ancient times universally regarded as the capital of all Ireland; so that in building palaces elsewhere it was usual to construct their principal houses and halls in imitation of those of Tara. It was the residence of the supreme kings of Ireland from prehistoric times, down to the sixth century, when it was deserted in the time of King Dermot, the son of Fergus Kervall, on account of St. Ruadan's curse. Although it has been abandoned to decay and ruin for thirteen centuries, it still presents striking vestiges of its ancient importance.

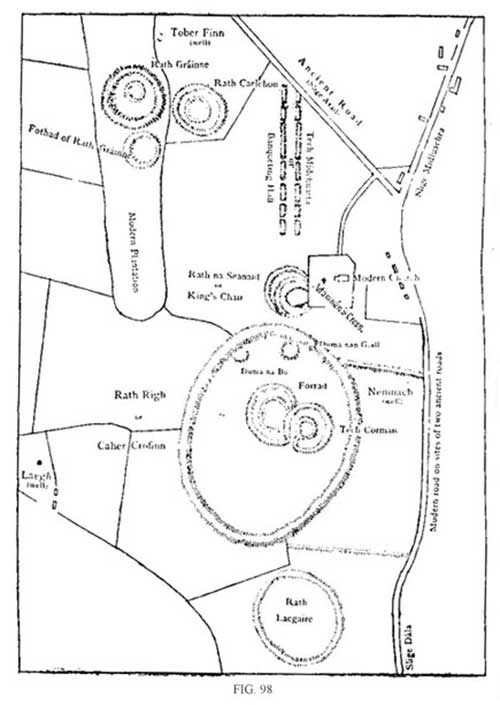

FIG. 98. Plan of Tara, as it exists at the present day. (From the two plans given by Petrie in his Essay on Tara).

Preserved in the Book of Leinster and other ancient manuscripts there are two detailed Irish descriptions of Tara, written by two distinguished scholars, one in the tenth century by Kineth O'Hartigan, and the other in the eleventh by Cuan O'Lochain. Both these learned men examined the remains personally, and described them as they saw them, after four or five centuries of ruin, giving the names, positions, and bearings of the several features with great exactness. More than sixty years ago Dr. Petrie and Dr. O'Donovan made a most careful detailed examination of the hill and its monuments; and with the aid of those two old topographical treatises they were able, without much difficulty, to identify most of the chief forts and other remains, and to restore their ancient names. The following are the most important features still existing, and they are all perfectly easy to recognise by any one who walks over the hill with the plan given here in his hand. It is to bo borne in mind that the forts now to be seen were the ramparts or defences surrounding and protecting the houses. The houses themselves, as has been already explained (p. 306), were of wood, and have, of course, all disappeared.

The principal fortification is Rath Righ [Rath-Ree], the 'Fort of the kings,' also called Caher Crofinn, an oval occupying the summit and southern slope of the hill, measuring 853 feet in its long diameter. The circumvallation can still be traced all round; and consisted originally of two walls or parapets with a deep ditch between. This seems to have been the original fort erected by the first occupiers of the hill, and the most ancient of all the monuments of Tara.

Within the enclosure of Rath Righ are two large mounds, the Forrad [Forra] and Tech Cormaic, beside each other, and having portions of their ramparts in common. The Forrad has two outer rings or ramparts and two ditches: its extreme outer diameter is nearly 300 feet. The name "Forrad" signifies 'a place of public meeting,' and also 'a judgment-seat,' cognate with Latin forum; so that it seems obvious that this is the structure referred to by the writer of the ancient Norse work called "Kongs Skuggsjo" or 'mirror for kings.' This old writer, in his description of Tara, says:—"And in what was considered the highest point of the city the king had a fair and well-built castle, and in that castle he had a hall fair and spacious, and in that hall he was wont to sit in judgment."

FIG. 99. The Mound called the Forrad at Tara (From Mrs Hall's Ireland).

On the top of the Forrad there now stands a remarkable pillar stone six feet high (with six feet more in the earth), which Petrie believed was the Lia Fail, the inauguration stone of the Irish over-kings, the stone that roared when a king of the true Milesian race stood on it (see p. 20); but recent inquiries have thrown grave doubts on the accuracy of this opinion.

Tech Cormaic ('Cormac's house') was so called from the illustrious King Cormac mac Art, who reigned A.D. 254 to 277. It is a circular rath consisting of a well marked outer ring or circumvallation, with a ditch between it and the inner space; the extreme external diameter being 244 feet. We may probably assign its erection to King Cormac, which fixes its age.

Duma nan Giall or the 'mound of the hostages,' situated just inside the ring of Rath Righ, is a circular earthen mound, 13 feet high, 66 feet in diameter at the base, with a flat top, 25 feet in diameter. The timber house in which the hostages lived, as already mentioned (pp. 22, 23), stood on the flat top.

A little to the west of the Mound of the Hostages stands another mound called Duma na Bo (the 'mound of the cow'), about 40 feet in diameter and 6 feet high. It was also called Glas Temrach (the 'Glas of Tara'), which would seem to indicate that the celebrated legendary cow called Glas Gavlin, which belonged to the Dedannan smith Goibniu, was believed to have been buried under this mound.

About 100 paces from Rath Righ on the north-east is the well called Nemnach ('bright' or 'sparkling'), so celebrated in the legend of Cormac's mill—the first mill erected in Ireland, for which see chap. xxi., below. A little stream called Nith ('shining') formerly ran from it, which at some distance from the source turned the mill. The well is now nearly dried up; but it could be easily renewed.

Rath na Seanaid (the 'rath of the synods': pron. Rath-na-Shanny), now popularly called "the King's Chair," has been partly encroached upon by the wall of the modern church: the two ramparts that surrounded it are still well-marked features. Within the large enclosure are two mounds, 106 and 33 feet in diameter respectively. Three Christian synods are recorded as having been held here, from which it had its name. Near the Rath of the Synods, and within the enclosure of the modern church, stood Adamnan's Cross, of which the shaft still remains, with a human figure rudely sculptured in relief on it.

On the northern slope of the hill are the remains of the Banqueting-Hall, the only structure in Tara not round or oval. It consists of two parallel mounds, the remnants of the side walls of the old Hall, which, as it now stands, is 759 feet long by 46 feet wide; but it was originally both longer and broader. It is described in the old documents as having twelve (or fourteen) doors: and this description is fully corroborated by the present appearance of the ruin, in which six door-openings are clearly marked in each side wall. Probably there was also a door at each end: but all traces of these are gone.

The whole site of the Hall was occupied by a great timber building, 45 feet high or more, ornamented, carved, and painted in colours. Within this the Feis or Convention of Tara held its meetings, which will be found described in chap. xxv., sect. 1, farther on. Here also were held the banquets from which the Hall was named Tech Midchuarta [Meecoorta], the 'mead-circling house'; and there was an elaborate subdivision of the inner space, with the compartments railed or partitioned off, to accommodate the guests according to rank and dignity. For, as will be seen in next chapter, they were very particular in seating the great company in the exact order of dignity and priority. From this Hall, moreover, the banqueting-halls of other great houses commonly received the name of Tech Midchuarta.

Rath Caelchon was so called from a Munster chief named Caelchon, who was contemporary with Cormac mac Art, third century. He died in Tara, and was interred in a leacht or carn, beside which was raised the rath in commemoration of him. The rath is 220 feet in diameter; and the very carn of stones heaped over the grave still remains on the north-east margin of the rath.

Rath Gráinne is a high, well-marked rath, 258 feet in diameter. It received its name from the lady Gráinne [Graunya: 2 syll.], daughter of King Cormac mac Art, and betrothed wife of Finn mac Cumail. She eloped with Dermot O'Dyna, and the whole episode is told in detail in the historic romance called "The Pursuit of Dermot and Gráinne."* This mound, and also the smaller mound beside it on the south called the Fothad [Foha] of Rath Gráinne, are now much hidden by trees.

A little north-west of the north end of the Banqueting-Hall, and occupying the space north of Rath Gráinne and Rath Caelchon, was the sheskin or marsh of Tara, which was drained and dried up only a few years before Petrie's time: but the well which supplied it, Tober Finn (Finn's well), still remains.

Rath Laegaire [Rath Laery], situated south of Rath Righ, was so called from Laegaire, king of Ireland in St. Patrick's time, by whom, no doubt, it was erected. It is about 300 feet in diameter, and was surrounded by two great rings or ramparts, of which one is still very well marked, and the other can be partially traced. Laegaire was buried in the south-east rampart of this rath, fully armed and standing up in the grave, with his face towards the south as if fighting against his enemies, the Leinster men. (See chap. xxvii., sect. 3, farther on.)

West of Rath Righ was the well called Laegh [Lay], a name signifying 'calf': it is now dried up, though the ground still remains moist. In this well, according to the seventh-century Annotations of Tirechan, St. Patrick baptised Lis first convert at Tara, Erc the son of Dego, who afterwards became bishop of Slane, and who is commemorated in the little hermitage still to be seen beside the Boyne (p. 137, above).

The five main sliges [slees], or roads, leading from Tara in five different directions through Ireland, will be found described in chap. xxiv., sect. 1. Of these portions of three are still traceable on the hill. The modern road traverses and covers for some distance the sites of two of them, Slige Dala and Slige Midluachra, as seen on the plan: Slige Asail still remains, and is sometimes turned to use.

In one of the ancient poetical accounts quoted by Petrie, it is stated that the houses of the general body of people who lived near Tara were scattered on the slope and over the plain east of the hill.

In connexion with Tara, two other great circular forts ought to be mentioned. A mile south of Rath Righ lies Rath Maire, which is very large—673 feet in diameter; it forms a striking object as seen from the hill, and is well worth examining. It was erected, according to one account, by Queen Maive (not Queen Maive of Croghan), wife of Art the solitary, the father of King Cormac mac Art, which would fix the period of its erection as the beginning of the third century. The other fort is Rathmiles, 300 feet in diameter, lying one mile north of the Banqueting-Hall: but nothing is known of its history.

After the abandonment of Tara, the kings of Ireland took up their abode where they pleased, each commonly in one of his other residences, within his own province or immediate territory. One of these seats was Dun-na-Sciath (the 'Fort of the Shields': pron. Doon-na-Skee), of which the circular fort still remains on the western shore of Lough Ennell in County Westmeath. Another was at Rath, near the western shore of Lough Lene in Westmeath, two miles from the present town of Castlepollard. This residence was occupied for a time by the Danish tyrant Turgesius, so that the fort, which is one of the finest in the country, is now known as Dun-Torgeis or Turgesius' fort; while the Old Irish name has been lost.

It has been already stated (p. 15) that Tuathal the Legitimate, king of Ireland in the second century, built four palaces at Tara, Tailltenn, Ushnagh, and Tlachtga. The fort of Tlachtga still remains on the summit of the Hill of Ward near the village of Athboy in Meath. There were royal residences also at Dunseverick in Antrim, the ancient Dun-Sobairce; at Rathbeagh on the Nore, where the rath is still to be seen; at Dun-Aenguis on Great Aran Island; and on the site of the present Baily Lighthouse at Howth, where several of the defensive fosses of the old palace-fort of Dun-Criffan can still be traced.

« previous page | contents | start of chapter | next page »

NOTE

* This fine story will be found in Joyce's Old Celtic Romances.