Irish Churches and Monastic Buildings

From A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland 1906

« previous page | contents | start of chapter | next page »

CHAPTER VI....continued

6. Buildings and other Material Requisites.

Churches and Monastic Buildings.—Nearly all the churches in the time of St. Patrick, and for several centuries afterwards, were of wood. But this was by no means universally the case; for little stone churches were erected from the earliest Christian times.

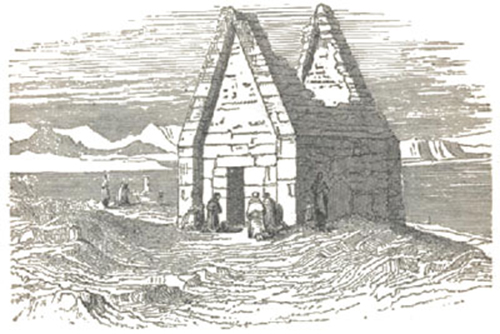

FIG. 42. St. Mac Dara's primitive church on St. Mac Dara's Island, off the coast of Galway. Interior measurement 15 feet by 11. (From Petrie's Round Towers).

The early churches, built on the model of those introduced by St. Patrick, were small and plain, seldom more than sixty feet long, sometimes not more than fifteen, always a simple oblong, never cruciform; almost universally placed east and west, with the door in the west end.

As Christianity spread, the churches became gradually larger and more ornamental, and a chancel was often added at the east end, which was another oblong, merely a continuation of the larger building, with an arch between.

FIG. 43. St. Douloghs stone-roofed Church, four miles north of Dublin. St. Duilech, one of the early Irish saints, settled here and built a church; but the present church (here figured) is not older than the thirteenth century. (From Wakeman's Handbook of Irish Antiquities).

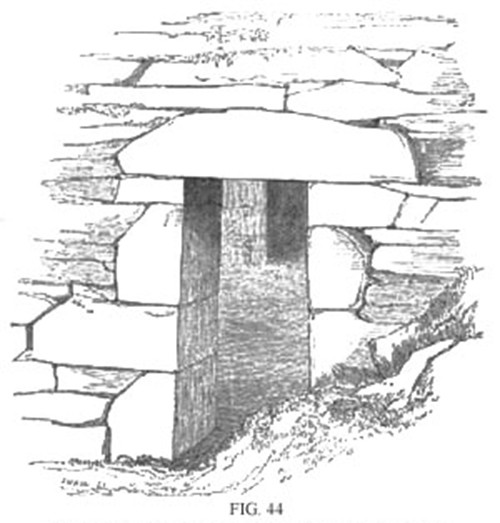

The jambs of both doors and windows inclined, so that the bottom of the opening was wider than the top: this shape of door or window is a sure mark of antiquity. The doorways were commonly constructed of very large stones, with almost always a horizontal lintel: the windows were often semi-circularly arched at top, but sometimes triangular-headed.

FIG. 44. Doorway of Tempull Caimhain in Aran, with sloped sides

The remains of little stone churches, of these antique patterns, of ages from the fifth or sixth century to the tenth or eleventh, are still to be found all over Ireland.

The small early churches, without chancels, were often or generally rooted with flat stones, of which Cormac's chapel at Cashel, St. Doulogh's near Dublin (p. 156), St. Columb's house at Kells (p. 140, supra), and St. Mac Dara's Church (p. 155, supra), are examples. In early ages churches were often in groups of seven—or intended to be so—a custom still commemorated in popular phraseology, as in "The Seven Churches of Glendalough."

In the beginning of the eleventh century, what is called the Romanesque style of architecture, distinguished by a profusion of ornamentation—a style that had previously been spreading over Europe—was introduced into Ireland. Then the churches, though still small and simple in plan, began to be richly decorated. We have remaining numerous churches in this style: a beautiful example is Cormac's chapel on the Rock of Cashel, erected in 1134 by Cormac Mac Carthy, king of Munster (figured on title-page).

Nemed or Sanctuary.—The land belonging to and around a church—the glebe-land—was a sanctuary, and as such was known by the names of Nemed [neveh] meaning literally 'heavenly' or 'sacred,' and Termann or Termon, meaning 'boundary'; for the sanctuary was generally marked off at the corners by crosses or pillar-stones. Once a culprit, fleeing from enraged pursuers, succeeded in getting inside the boundary, he was safe for the time; for no one durst violate the sanctuary by molesting him. But when the immediate occasion passed, he was given up to be dealt with by the ordinary tribunals.

It was usual for the founders of churches to plant trees—oftenest yew, but sometimes oak or ash—for ornament and shelter, round the church and cemetery, and generally within the sanctuary. These little plantations were subsequently held in great veneration, and it was regarded as an outrageous desecration to cut down one of the trees, or even to lop off a branch. They were called Fidnemed [finneveh], 'sacred grove,' or grove of the nemed or sanctuary: from fid (fih), 'a wood or grove.'

The most general term for a church was, and is still, cill [kill], derived from Lat. cella; but there were several other names.

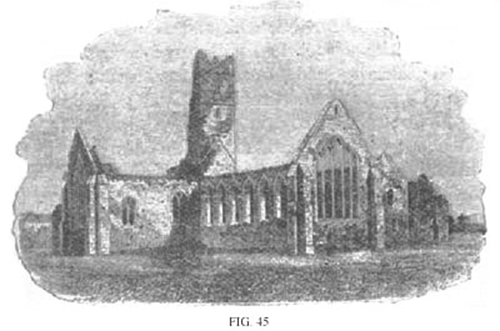

FIG. 45. Dominican Abbey, Kilmallock: founded in 1291 by Gilbert Fitzgerald. (From Kilkenny Archaeological Journal).

Later Churches.—Until about the period of the Anglo-Norman invasion all the churches, including those in the Romanesque style, were small, because the congregations were small. But about the middle of the twelfth century the old Irish style of church architecture began to be abandoned, chiefly through the influence of the Anglo Normans, who were, as we know, great builders. Towards the close of the century, when many of the great English lords had settled in Ireland, they began to indulge their taste for architectural magnificence, and the native Irish chiefs imitated and emulated them; large cruciform churches in the pointed style began to prevail; and all over the country splendid buildings of every kind sprang up. Then were erected—some by the English, some by the Irish—those stately abbeys and churches of which the ruins are still to be seen; such as those of Kilmallock and Monasteranenagh in Limerick; Jerpoint in Kilkenny; Grey Abbey in Down; Bective and Newtown in Meath; Sligo; Quin, Corcomroe, and Ennis in Clare; Ballintober in Mayo; Knockmoy in Galway; Dunbrody in Wexford; Buttevant; Cashel; and many others.