Irish Missions to Foreign Lands

From A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland 1906

« previous page | contents | start of chapter | next page »

CHAPTER VI....continued

Missions to Foreign Lands.—Whole crowds of ardent and learned Irishmen travelled to the Continent in the sixth, seventh, and succeeding centuries, spreading Christianity and secular knowledge everywhere among the people. "What," says Eric of Auxerre (ninth century), in a letter to Charles the Bald, "what shall I say of Ireland, who, despising the dangers of the deep, is migrating with almost her whole train of philosophers to our coasts?"

FIG. 39. Shrine, now preserved in Copenhagen, showing the Opus Hibernicum, one of the Continental traces of Irish missionaries. Made either by an Irish artist or by one who had learned from Irish artists (From Journ. Roy. Soc. Antiq. Irel.).

"A characteristic still more distinctive of the Irish monk"—writes Montalembert—"as of all their nation, was the imperious necessity of spreading themselves without, of seeking or carrying knowledge and faith afar, and of penetrating into the more distant regions to watch or combat paganism": and a little further on he speaks of their "Passion for pilgrimage and preaching."

These men, on their first appearance on the Continent, caused much surprise, they were so startlingly different from those preachers the people had been accustomed to. They generally—as we have said—went in companies. They wore a coarse outer woollen garment, in colour as it came from the fleece, and under this a white tunic of finer stuff. They were tonsured bare on the front of the head, while the long hair behind flowed down on the back: and the eyelids were painted or stained black. Each had a long stout cambutta, or walking-stick: and slung from the shoulder a leathern bottle for water, and a wallet containing his greatest treasure—a book or two and some relics. They spoke a strange language among themselves, used Latin to those who understood it, and made use of an interpreter when preaching, until they had learned the language of the place.

Few people have any idea of the trials and dangers they encountered. Most of them were persons in good position, who might have lived in plenty and comfort at home. They knew well, when setting out, that they were leaving country and friends probably for ever; for of those that went, very few returned. Once on the Continent, they had to make their way, poor and friendless, through people whose language they did not understand, and who were in many places ten times more rude and dangerous in those ages than the inhabitants of these islands: and we know, as a matter of history, that many were killed on the way. Yet these stout-hearted pilgrims, looking only to the service of their Master, never flinched. They were confident, cheerful, and self-helpful, faced privation with indifference, caring nothing for luxuries; and when other provisions failed them, they gathered wild fruit, trapped animals, and fished, with great dexterity and with any sort of next-to-hand rude appliances. They were rough and somewhat uncouth in outward appearance: but beneath all that they had solid sense and much learning. Their simple ways, their unmistakable piety, and their intense earnestness in the cause of religion caught the people everywhere, so that they made converts in crowds.

Irish professors and teachers were in those times held in such estimation that they were employed in most of the schools and colleges of Great Britain, France, Germany, and Italy. The revival of learning on the Continent was indeed due in no small degree to those Irish missionaries; and the investigations of scholars among the continental libraries are every year bringing to light new proofs of their industry and zeal for the advancement of religion and learning. To this day, in many towns of France, Germany, Switzerland, and Italy, Irishmen are venerated as patron saints. Nay, they found their way even to Iceland. We have the best authority for the statement that when the Norwegians first arrived at that island, they found there Irish books, bells, crosiers, and other traces of Irish missionaries; and the Irish geographer Dicuil, who wrote his Geography of the World in 825, records that in 795 some Irish ecclesiastics had sojourned in Iceland from February to August, where—as they told him—during a part of the time, they had sufficient light to transact their ordinary business all night through. Europe was too small for their missionary enterprise. We find a distinguished Irish monk named Augustin in Carthage in Africa, in the seventh century: and a learned treatise by him, written in very elegant Latin, on the "Wonderful Things of the Sacred Scripture," is still extant, and has been published. During his time also two other Irish monks named Baetan and Mainchine laboured in Carthage. There were settlements of Irish monks also in the Faroe and Shetland Islands.

All over the Continent we find evidences of the zeal and activity of Irish missionaries. Twelve centuries after this host of good men had received the reward they earned so well, an Irish pilgrim of our own day —Miss Margaret Stokes—traversed a large part of the scene of their labours in Southern Europe, in a loving and reverential search for relics and memorials of them: and how well she succeeded, how numerous were the vestiges she found—abbeys, churches, oratories, hermitages, caves, crosses, altars, tombs, holy wells, baptismal fonts, bells, shrines, and crosiers, beautiful illuminated manuscripts in their very handwriting, place-names, passages in the literatures of many languages—all with their living memories, legends, and traditions still clustering round them—she has recorded in her two charming books, "Six Months in the Apennines," and "Three Months in the Forests of France." May she be welcomed by those she revered and honoured!

The Irish "Passion for pilgrimage and preaching" never died out: it is characteristic of the race. This great missionary emigration to foreign lands has continued in a measure down to our own day: for it may be safely asserted that no other missionaries are playing so general and successful a part in the conversion of the pagan people all over the world, and in keeping alight the lamp of religion among Christians, as those of Ireland.

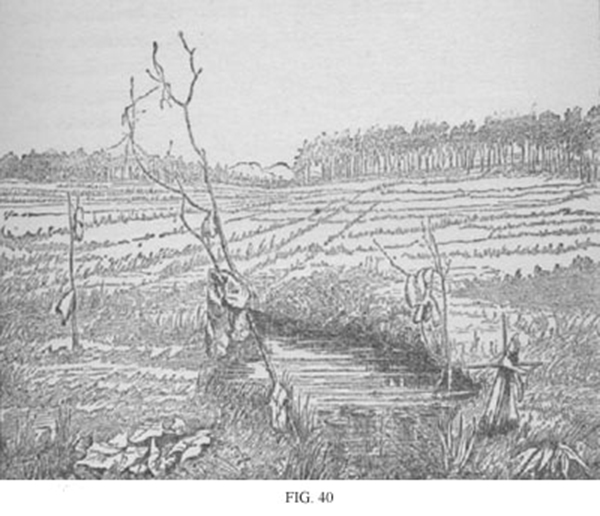

FIG. 40. Holy Well of St Dicuil, at Lure, in France: from Miss Stokes's Three Months in the Forests of France. This Dicuil (different from Dicuil the geographer) was a native of Leinster: educated at Bangor in Down: accompanied St. Columbanus to the Continent: founded a Monastery at Lure where he is now venerated as patron saint: died A.D. 625. Well still called by his name: much resorted to by pilgrims.

Take up any foreign ecclesiastical directory or glance through any newspaper account of religious meetings or ceremonies, or bold missionary enterprises in foreign lands; or look through the names of the governing bodies of Universities, Colleges, and Monasteries, in America, Asia, Australia, New Zealand—all over the world—and your eye is sure to light on cardinals, archbishops, bishops, priests, principals, professors, teachers, with such names as Moran, O'Reilly, O'Donnell, Mac Carthy, Higgins, Murphy, Walsh, Fleming, Fitzgerald, Corrigan, O'Gorman, Byrne, and scores of such-like, telling unmistakably of their Irish origin, and proving that the Irish race of the present day may compare not unfavourably in missionary zeal with those of the times of old. As the sons of Patrick, Finnen, and Columkille took a leading part in converting the people of Britain and the Continent, so it would seem to be destined that the ultimate universal adoption of Christianity should be mainly due to the agency of Irish missionaries.