Irish Monastic Life

From A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland 1906

« previous page | contents | start of chapter | next page »

CHAPTER VI....continued

Monastic Life.—The religious houses of this second class of Irish saints constituted the vast majority of the monasteries that flourished in Ireland down to the time of their suppression by Henry VIII. These are the monasteries that figure so prominently in the ecclesiastical history of Ireland: and it will be interesting to look into them somewhat closely and see how they were managed, and how the monks spent their time.

For spiritual direction, and for the higher spiritual functions, such as those of ordination, confirmation, consecration of churches, &c., a bishop was commonly attached to every large monastery and nunnery. The monastic discipline was very strict, turning on the one cardinal principle of instant and unquestioning obedience. There was to be no idleness: everyone was to be engaged, at all available times, in some useful work; a regulation which appears everywhere in our ecclesiastical history.

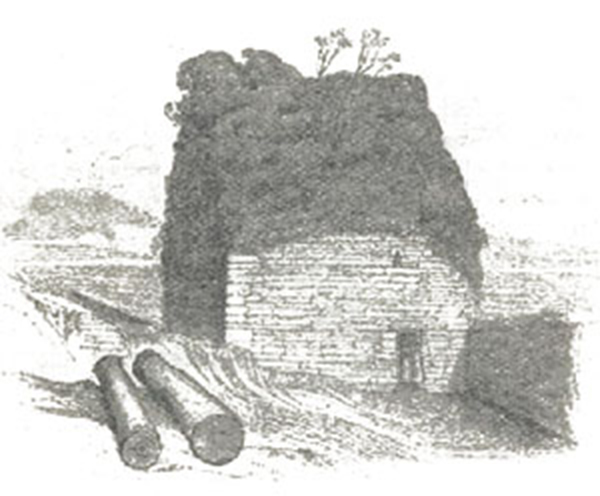

FIG. 38. "St. Columb's or Columkille's House" at Kells, Co. Meath: interior measurement about 16 feet by 13: walls 4 feet thick. An arched roof immediately overhead inside: between which and the steeply sloped external stone roof is a small apartment for habitation and sleeping, 6 feet high. A relic of the second order of saints and probably coeval with St Columkille, sixth century. (From Petrie's Round Towers).

The monasteries of the Second Order were what are commonly known as "cenobitical" or community establishments: i.e., the inmates lived, studied, and worked in society and companionship, and had all things in common. In sleeping accommodation there was much variety; in some monasteries each monk having a sleeping-cell for himself; in others three or four in one cell. In some they slept on the bare earth: in others they used a skin, laid perhaps on a little straw or rushes. Their food was prepared in one large kitchen by some of their own members specially skilled in cookery; and they took their meals in one common refectory. The fare, both eating and drinking, was always simple and generally scanty, poor, and uninviting: but on Sundays and festival days, and on occasions when distinguished persons visited, whom the abbot wished to honour, more generous food and drink were allowed.

When the founder of a monastery had determined on the neighbourhood in which to settle, and had fixed on the site for his establishment, he brought together those who had agreed to become his disciples and companions, and they set about preparing the place for residence. They did all the work with their own hands, seeking no help from outside. While some levelled and fenced in the ground, others cut down, in the surrounding woods, timber for the houses or for the church, dragging the great logs along, or bringing home on their backs bundles of wattles and twigs for the wickerwork walls. Even the leaders claimed no exemption, but often worked manfully with axe and spade like the rest.

Every important function of the monastery was in charge of some particular monk, who superintended if several persons were required for the duty, or did the work himself if only one was needed. These persons were nominated by the abbot, and held their positions permanently for the time. There was a tract of land attached to almost every monastery, granted to the original founder by the king or local lord, and usually increased by subsequent grants: so that agriculture formed one of the chief employments. When returning from work in the evening, the monks brought home on their backs whatever things were needed in the household for that night and next day. Milk was often brought in this manner in a vessel specially made for the purpose: and it was the custom to bring the vessel straight to the abbot, that he might bless the milk before use. In this field-work the abbot bore a part in several monasteries: and we sometimes read of men, now famous in Irish history—abbots and bishops in their time—putting in a hard day's work at the plough.

Those who had been tradesmen before entering were put to their own special work for the use of community and guests. Some ground the corn with a quern or in the mill; some made and mended clothes; some worked in the smith's forge or in the carpenter's workshop; while others baked the bread or cooked the meals.

Attached to every cenobitical monastery was a 'guest house' or hospice, for the reception of travellers. Some of the inmates were told off for this duty, whose business it was to receive the stranger, take off his shoes, wash his feet in warm water, and prepare supper and bed for him. In the educational establishments, teaching afforded abundant employment to the scholarly members of the community. Others again worked at copying and multiplying books for the library, or for presentation outside; and to the industry of these scribes we owe the chief part of the ancient Irish lore, and other learning, that has been preserved to us. St. Columkille devoted every moment of his spare time to this work, writing in a little wooden hut that he had erected for his use at Iona. It is recorded that he wrote with his own hand three hundred copies of the New Testament, which he presented to the various churches he had founded. Some spent their time in ornamenting and illuminating books—generally of a religious character, such as copies of portions of Scripture: and these men produced the wonderful penwork of the Book of Kells and other such manuscripts.

Others were skilled metal-workers, and made crosiers, crosses, bells, brooches, and other articles, of which many are preserved to this day, that show the surpassing taste and skill of the artists. But this was not peculiar to Irish monks, for those of other countries worked similarly. The great English St. Dunstan, we know, was an excellent artist in metal-work. Some of the Irish monks too were skilled in simple herb remedies; and the poor people around often came to them for advice and medicine in sickness. When a monastery was situated on the bank of a large river where there was no bridge, the monks kept a curragh ready to ferry travellers across, free of charge.

In some monasteries it was the custom to keep a fire perpetually burning in a little chapel specially set apart for this purpose, to which the inmates attended in turn to supply fuel, so that the fire might never go out. The perpetual fire of Kildare, which was kept alight from the time of St. Brigit for many centuries, is commemorated in Moore's lines:—

“Like the bright lamp that shone in Kildare's holy fane,

And burned through long ages of darkness and storm:”

and there were similar fires in Kilmainham, Seirkieran, and Inishmurray.

Besides the various employments noticed in the preceding pages, the inmates had their devotions to attend to, which were frequent, and often long: and in most monasteries they had to rise at the sound of the bell in the middle of the night, and go to the adjacent church to prayers.