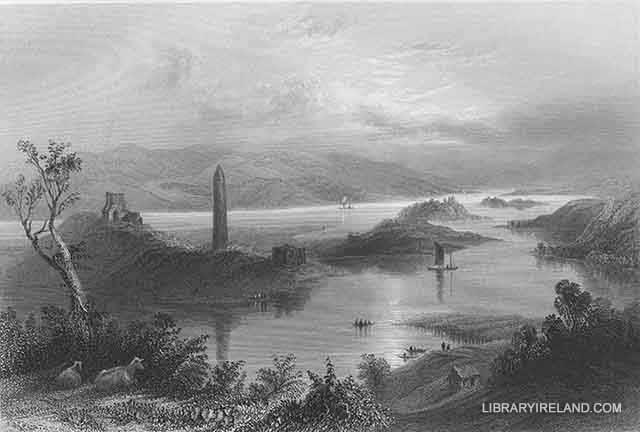

Enniskillen and Devenish Island

The road from Derry to Enniskillen follows the Foyle for a considerable distance, and a most lovely river it is—the deficiency of wood on its shores alone proving an exception to the variety of its beauties. Coasting the northern side of Lough Erne, the traveller arrives at Enniskillen, the chief town of Fermanagh, and the most important in the north-west district of Ireland. The town stands on an elevated island, formed by the branching of the river Erne, in its progress from the upper to the lower lake. Though it cannot boast of high antiquity (says Fraser, in his excellent Guide-Book to Ireland), it may fairly claim what is of far more modern importance—a comparatively well-built, well-arranged, and well-governed town, a steady trade, and many respectable inhabitants.

The environs of Enniskillen are very interesting, as well from the naturally rich and broken character of the country as from its comparative improvement. Two miles from the town, in the entrance to the Lower Lough Erne, stands DEVENISH ISLAND, the most important of the "three hundred and sixty-five islands" said to dot the bosom of this lovely lake. Most of the other islets present a green and cheerful picture to the eye, but Devenish, says the author of The Story of a Life, "has a deader, duller, paler look than any other of the islets of the lake." A writer in a recent publication demurs to this description, and declares the island to be remarkably fertile, and, of course, cheerful in its aspect. The ruins of a supposed monastery, of an ancient abbey, and the cell of a venerable man, stand near the centre of this lonely isle; while the tall shaft of the ancient pillar-tower raises its grey height—"like a mountain of some patient and abiding grief."

Around this place of silence and of ruin, reminiscences of mortality lie scattered, in a way but little grateful to the living; the rude stones that lie upon the graves are so stained with weather, and time-decayed, and overgrown with rank weeds, that they are scarcely approachable, and thus their legends are lost. The crypt of the founder stands roofless amidst this scene of decay, and the stone coffin that once enclosed his breast is firmly buried in the earth beside it. There is a veneration, a religious feeling, or perhaps a superstition, attached to Devenish and its ruined piles. In no country of Europe is more tenderness expressed for the lass of relatives and kindred, or so much posthumous affection manifested in the respect paid to their remains. Perhaps it is imagined that those who flourished at an age nearer to the foundation of Christianity were necessarily more holy, and that the stream is sullied by the length of its course. Whatever be the cause, the veneration for ancient cemeteries, crosses, and ecclesiastical ruins is unbounded.