Clonmacnois - Irish Pictures (1888)

From Irish Pictures Drawn with Pen and Pencil (1888) by Richard Lovett

Chapter VI: The Shannon … continued

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Book Contents | Next Page »

Athlone is the most convenient starting-point for an excursion that should rank among the most important in Ireland, viz., a visit to Clonmacnois. At one time steamers plied down the Shannon from Athlone to Killaloe; but at the time of writing (1888) this is not the case. A steamer may occasionally go, but this happens too seldom to be of much service to strangers. This is a misfortune, for the trip is one of the best in Ireland. But to visit Clonmacnois the visitor can either hire a row boat and pull down the river, or go by road in a car, a distance of nearly twelve miles. By the latter method he sees to advantage a fine stretch of country, and enjoys some strong fresh air. The district is undulating, and the road winds along past country houses, through tiny hamlets, by deserted cabins, and over large stretches of bog, giving every here and there fine views over the Shannon Valley, and at last brings the visitor to the far-famed 'Meadow of the Son of Nos,' this being the real meaning of the name Clonmacnois.

This famous ecclesiastical establishment is well situated upon a knoll overlooking a wide sweep and curve of the Shannon. Within a Cashel, or stone enclosure, are some magnificent architectural remains, and upon another knoll, only a stone's throw distant, are traces of the ancient structure which served as the episcopal palace and castle of the O'Melaghlins. Clonmacnois was founded in A.D. 546 by St. Kieran on land given by Dermot MacCervail, King of Ireland. It soon became a city, and the seat of a bishopric, and established a great reputation as a seat of learning. In later times it became a favourite cemetery for kings and nobles. It was ravaged again and again by the Northmen, and the centuries have not treated it very kindly. But notwithstanding these vicissitudes, and the destructive influences that have been exerted upon it, it is yet second to no spot in Ireland for the number and interest of its wonderful remains.

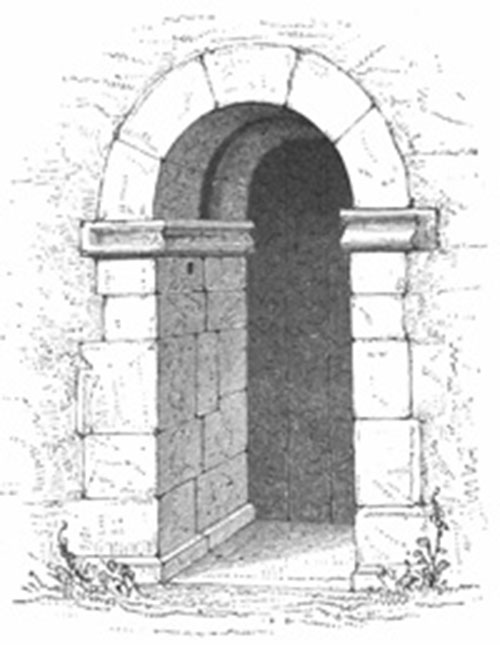

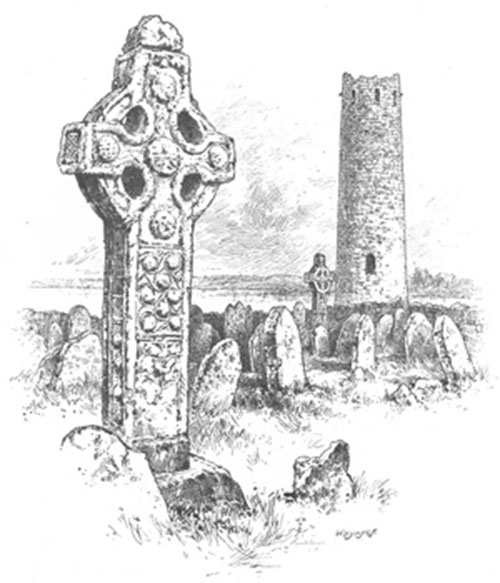

These consist of churches, round towers, stone crosses, and ancient tombs. The building known as Temple Conor is now used as a parish church. This church dates from the tenth century, but of the original edifice, in all probability, the doorway, of which we give an illustration, is the only part extant. The Daimhliag Mor, or Great Church, was built in 909 by Flann, King of Ireland, and Colman, Abbot of Clonmacnois. It was rebuilt in the fourteenth century; but the splendid west doorway is in all probability a part of the original structure. The north doorway, which is enriched by three sculptures placed above the arch—St. Patrick in his pontificals, with St. Francis on one side and St. Dominic on the other—is of the later date. Standing within the church and looking out through the western door, the visitor sees one of the finest ancient crosses in Ireland. It has evidently been placed there purposely, and, seen through the frame of a doorway that was two centuries old when Henry II. landed in Ireland, standing out boldly and clearly as it does against the distant sky, this great, time-worn cross deeply impresses the imagination. About its origin there is no doubt. Upon the west side is the inscription, 'A prayer for Flann, son of Maelsechlainn,' and upon the eastern, 'A prayer for Colman who made this cross on the King Flann.' King Flann died in A.D. 916, and Abbot Colman in 924 or 926, and this magnificent monument, 15 feet high, and so placed that no worshipper could leave the church without seeing it, has for over nine hundred years testified to the piety of the monarch, and to the skill of the men by whom he was served and remembered. On the side of the cross facing the church are sculptures relating to the original foundation of that edifice by St. Kieran, who is represented with a hammer in one hand and a mallet in the other. The other side has carvings depicting scenes in our Lord's Passion. A short distance to the south stands another large cross, nearly as fine a specimen of this kind of art as Flann's. It is a good example of the embossed ornamentation common in Irish sculpture of this period. The engraving on page 146 represents this in the foreground, with Flann's cross and the big Round Tower in the middle, and the Shannon in the distance. The numerous tombstones, ancient and modern, testify to the sanctity of Clonmacnois.

There are two Round Towers. That shown in the engraving, although ruined in the upper portion, is one of the largest and finest in the country. It is contemporary, in all probability, with Flann's Church. Caesar Otway's description of it is not only appropriate to this, but applies to many other specimens of this characteristic Irish building. 'It was high enough,' he writes, 'to take cognisance of the coming enemy, let him come from what point he might; it commanded the ancient causeway that was laid down at considerable expense across the great bog on the Connaught side of the Shannon; it looked up and down the river, and commanded the tortuous and sweeping reaches of the stream, as it unfolded itself like an uncoiling serpent along the surrounding bogs and marshes; it could hold communication with the holy places of Clonfert; and from the top of its pillared height send its beacon light towards the sacred isles and anchorite retreats of Lough Ree; it was large and roomy enough to contain all the officiating priests of Clonmacnois, with their pyxes, vestments, and books; and though the Pagan Dane or wild Munsterman might rush on in rapid inroad, yet the solitary watcher on the tower was ready to give warning, and collect within the protecting pillar all holy men and things, until the tyranny was overpast.'

This extract admirably describes the most important functions of these curious buildings. No point in Irish archaeology has been more controverted than the origin and use of the Round Towers. Dr. Petrie has, in the opinion of most scholars, settled the question once for all in his well-known essay. They were watch-towers from which the approach of an enemy might be descried in time to make adequate preparations for defence. They were secure places of refuge, into which the monks and all connected with the monastery could safely retire with their valuables, when they were unable otherwise to withstand the assaults of the Northmen. They were also belfrys or bell-towers, and this may be described as their normal use. In them hung the bell or bells that summoned the various members of the monastery to their duties, and that announced the various services as they were held.

During five or six hundred years the great tower of Clonmacnois discharged these varied functions. It was built, in Dr. Petrie's view, about A.D. 908. In the Annals of the Four Masters, under A.D. 1124, we read: 'The finishing of the cloictheach (the Irish term used to describe these towers, and meaning belfry) of Clonmacnois by O'Malone, successor of St. Kieran.' This entry referred in all probability not to the erection but to a restoration of the tower. And as late as 1552, in the same Annals, the following entry appears: 'Clonmacnois was plundered and devastated by the Galls (English) of Athlone, and the large bells were carried from the cloictheach. There was not left, moreover, a bell, small or large, an image, or an altar, or a book, or a gem, or even glass in a window, from the wall of the church out, which was not carried off. Lamentable was this deed, the plundering of the city of Ciaran, the holy patron.'

Over a hundred specimens of these buildings, some of them quite perfect, have survived to this day. They resemble each other in plan and construction, some exhibiting better masonry than others, and local peculiarities in some instances determining the position of the windows and the door. Usually this is found, as shown in the engraving on page 146, about 15 feet from the ground. This fact strengthens the view that one main purpose the towers served was to afford a safe refuge. When the defenders had entered, and the ladder by which they ascended was removed, they were practically unassailable by any weapons the Northmen possessed. These doors were sometimes decorated with ornamental carvings, but more generally consisted of simple arches.

The second tower at Clonmacnois belongs to the building known as Teampul Finghin, or Fineen's Church, dating, it is supposed, from the tenth century, of which only the chancel and round tower remain. In this instance the tower is perfect. It is much smaller than its companion, being only fifty-six feet high, and the doorway is on a level with the floor of the chancel and opens into it.

Many interesting tombstones exist at Clonmacnois, and many interesting objects of antiquity have been found there. Among these the museum of the Royal Irish Academy in Dublin possesses a crozier which once belonged to the bishops of Clonmacnois, and which is a very fine specimen of this kind of Irish art.

But here, as at Glendalough, although a minute acquaintance with the history and archaeology adds greatly to the value and educational value of a visit, the absence of these by no means destroys the interest of Clonmacnois. The situation is very lovely, the view of the Shannon very fine, the ride or the row from Athlone enjoyable, and even the most superficial inspection of the towers and arches and ruined churches can hardly fail to enrich the visitor with new and deep impressions of the vigorous religious life of Ireland eight hundred or a thousand years ago.

Leaving Clonmacnois and following the course of the great river, Shannon-bridge and Banaghel are passed, and finally we reach Portumna. Here a swivel bridge, 766 feet long, has replaced an earlier wooden structure built by Lemuel Cox, the architect of the still extant Waterford Bridge. There is nothing of special interest in Portumna, but the district around has become notorious in recent years on account of its agrarian troubles. Into these, however, it is not our function to enter.

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Book Contents | Next Page »