Monastery on the Great Skellig - Irish Pictures (1888)

From Irish Pictures Drawn with Pen and Pencil (1888) by Richard Lovett

Chapter V: Glengariff, Killarney, and Valentia … continued

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Book Contents | Next Page »

Lonely indeed is the Great Skellig, bracing the air, and picturesque the views afforded by its own rugged cliffs, and those of the Lesser Skellig, its only near neighbour; but these would hardly form sufficient attractions to draw the visitor, were it not for the well-known fact that over one thousand years ago this solitary peak was the home of a busy and devout life. This was the St. Michael's Mount of Ireland, and its history is dim and shadowy in the very early ages of Church history. Many remains of early architecture, and some of them in wonderful preservation, are still to be seen upon the summit of the rock, and form the chief magnet which draws the traveller hither.

As one begins to grow more familiar with the scene, and to lose something of the awe which it at first inspires, one cannot but feel that a true instinct brought hither the monks in those far-off days. Starting from the lighthouse, the ascent is very fine. 'Above, the rock towers higher and higher, and is split into fantastic forms like the opened leaves of a book set upright, with narrow strips of bright green running between them, or fringing the horizontal blocks of the strata at their feet. When the sunlit mists or vapours sweep in driving clouds above them, the effect is in the highest degree mysterious and beautiful; but when at one moment these mists rise so as entirely to conceal the heights, and at the next they vanish as if at the touch of some unseen hand, and the cliff again stands revealed against the blue unfathomed sky, it seems as if the whole scene were called up by some strange magician's wand.

'The ancient approach to the monastery from the landing-place was on the north-east side. There are 620 steps from a point of the cliff which is about 120 feet above the level of the sea, up to the monastery. The rest of this flight of steps is broken away, and a new approach was cut in very recent times. The old stairs run in a varying line; the steps, which grow broader towards the upper half of the ascent, are lined with tufts and long cushions of the sea-pink, and at each turn the ocean is seen breaking in foam hundreds of feet below.'[3]

For many centuries the island has been the scene of pilgrimage, but the author could get no certain information as to when the practice ceased, if it has come to an end. Half way up the ascent is a little valley between the two peaks, in shape something like a saddle, and known as ' Christ's Saddle,' or the Garden of the Passion. From this place what is known as the Way of the Cross rises up, and at one part a rock has been shaped into the form of a rude cross. The path still rises, and at length brings the climber to the Cashel or enclosing wall of the monastery. And a wonderful spot this is. Around is the sky and sea. In the far distance is the outline of the Irish coast, but a most peculiar effect is produced upon the mind and spirit by the physical properties of the spot.

One cannot at first shake off the sense of insecurity; then the loneliness of a high elevation oppresses one; and yet the disturbing influence of these feelings is soothed by the consciousness that the spot is rich in its spiritual helpfulness. It is good for the soul to be thus lifted out of and away from all the mean and petty detail of life, to escape from the wearing friction of the selfish every-day life, and to be alone with the noblest natural features—the wide sky, the broad and health-giving ocean, the immovable rock, so firmly rooted that through countless generations the Atlantic surges have vainly thundered against it. Standing there one feels that when other countless generations shall have passed the rock will abide there still.

Another element in this potent charm is the conviction that upon this rock the men of the past met, and fought, and conquered those foes with which the true spirit of man is ever at war. We might not be able to use the forms of prayer through which those men expressed their penitence, their praise, their aspiration. We may differ altogether from their conception of life, and think that they were better placed when on the mainland, and nearer the full tide of their brethren's life, and toils, and conflicts and temptations. But few can stand on that lonely elevation, bound up indissolubly as it is with so much that is sublime in the present, and hallowed in the past, without feeling lifted, for a time at least, out of the low commonplace, and the mean selfishness of too much of our daily life.

The spirit recognises that here in past ages men sought the great Father in heaven, and found that God is love; here, they yearned for pardon and found the true 'way of the cross,' the forgiveness of sins made possible because Jesus Christ died on the cross, and granted to erring man, for the Father, having given the Son, with Him freely gave them all things. These rude, humble stone cells become radiant as one feels that in them answers to prayer were obtained, and that in them men, our brothers, felt the power of the Spirit of God to cleanse, to inspire, to recreate, and to exalt. And this feeling deepens as one remembers the comparative purity of that early Irish Church, which has impressed upon the world's history such personalities as Patrick, Columbkille and Columbanus. Seen under the influence of such associations, one feels the truth of these words: 'The scene is one so solemn and so sad that none should enter here but the pilgrim and the penitent. The sense of solitude, the vast heaven above, and the sublime monotonous motion of the sea beneath, would but oppress the spirit, were not that spirit brought into harmony with all that is most sacred and grand in Nature, by the depth and even by the bitterness of its own experience.'[4]

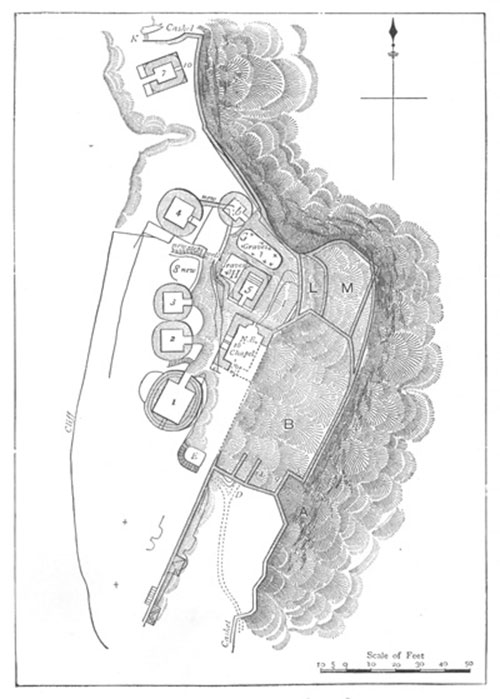

In order to give the reader a notion of what one of these early Irish monasteries was like, the accompanying plan has been engraved. To render it quite clear, a brief explanation is needful. The buildings which form this monastery occupy a piece of ground measuring about 180 feet in length by from 80 to 100 feet in width. They are, first—the Church of St. Michael, two small oratories, Nos. 5 and 7 in ground plan, and six anchorite cells or dwelling-houses. There are also two wells and five leachta, or places of entombment, and several rude crosses. This group of buildings was enclosed on one side by the rock, against which they were partly built, and then by the Cashel, which ran along the edge of the precipice. The old entrance was at A (see ground plan). It consisted of a flight of steps through a door, which has long been stopped up. It leads into a small level piece of ground, called the Monk's Garden, at B, then by another flight to the doorway, D, which is also closed.

St. Michael's Church (marked chapel in plan) is not the original church of the monastery, but a later structure. It is peculiar, inasmuch as it faces the north-east; and its walls, now only a mass of ruins, were, but a few years since, nearly perfect. More interesting are the old cells, of which the Cashel contains several fine specimens. No. 1 is a circular structure having what is known as a bee-hive roof. Each stone projects on the inside a little beyond the one beneath, and gradually in this way the roof comes to a point closed by a single stone. These erections belong to a very ancient period of early Irish ecclesiastical architecture. The interior is 16 feet 6 inches high, and the walls are 6 feet thick. No. 2 is rectangular inside, better built than No. 1, and composed of larger stones, some of which are dressed. Nos. 3 and 4 are similar structures. No. 5 was an oratory, and is quadrangular up to the height of 8 feet, and then becomes an oval dome. The wall at the door is 4 feet 8 inches thick. No. 6 is a cell, having on the inside 'two rows of projecting stones or pegs, which here, as also in the other cells, may have been the supports of book-satchels.' No. 7 is an oratory, stands alone, and gives evidence of being the oldest of the whole group of buildings by reason of the very rude nature of the building. No. 8, for a similar reason, is supposed to be the oldest of the cells. It is partly hidden by a wall built up against it in modern times.

G. H. are old burial-grounds, containing many rude crosses and pillar stones.

NOTES

[3] Dunraven's Notes on Irish Architecture, pp. 27, 28.

[4] Dunraven's Notes on Irish Architecture, vol. i., p. 30.

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Book Contents | Next Page »