Irish Music before the Anglo-Norman Invasion

ALTHOUGH in ancient Erin, from the ninth to the middle of the eleventh century, the Danish incursions, as well as internecine conflicts, were serious obstacles to the cultivation of music, yet this very period was one of the greatest lustre for Irish music on the Continent. Of course, there are not wanting a few zealots who would fain have us believe that the Norsemen actually contributed to the preservation of churches and monasteries and schools in Ireland. It is strange to find Dr. Sigerson, in his otherwise excellent book, The Bards of the Gael and Gall, enunciating and upholding these peculiar views in reference to the Norsemen as regards Irish literature and music.

All our ancient chronicles are at one in describing the terrible vandalism committed by the Danes in the island of saints and scholars. Keating distinctly assures us that the Norsemen sought to destroy all learning and art in Ireland. His words are most emphatic:—"No scholars, no clerics, no books, no holy relics, were left in church or monastery through dread of them. Neither bard, nor philosopher, nor musician, pursued his wonted Profession in the land."

To come to concrete examples, we are told that "Brian Boru's March" and "The Cruiskeen Lawn" are good specimens of "Scandinavian music." This statement is quite erroneous. Both of these airs are genuinely Irish in construction, though I gravely doubt whether either of them dates from the Norse period, or even from mediaeval days.

Despite the troubled condition of Ireland during these two or three centuries, as Dr. Douglas Hyde writes, "she produced a large number of poets and scholars, the impulse given by the enthusiam of the sixth and seventh centuries being still strong upon her." Among the distinguished bards of the tenth century was Flann Mac Lonain. In one of his eight poems that have come down to our days he describes a harper called Ilbrechtach, of Slieve Aughty, near Kinalehin.

King Brian, ere his sad death at the glorious victory of Clontarf, in 1014. did a great deal towards repairing the ravages wrought during three centuries. According to the "Wars of the Gael with the Gall," a valuable manuscript that was written during the first quarter of the eleventh century, Brian "sent professors and masters to teach wisdom and knowledge," but he was compelled "to buy books beyond the sea and the great ocean, because the writings and books of the churches and sanctuaries had been burned and drowned by the plunderers."

Whilst we must for ever lament the destruction of our ancient literary and musical manuscripts by the Norsemen, it is gratifying to know that some few musical treasures, written by Irish monks, still remain on the continent. Only to quote one instance, at Zurich, in the library of the Antiquarian Society, may yet be seen a fragment of an Irish Sacramentarium and Antiphonarium.

Our Irish St. Helias, a native of Monaghan, was elected Abbot of Cologne, in Germany, in 1015. He was the bosom friend of St. Heribert, and ruled the two monasteries of St. Martin's and St. Pantaleon's, from 1015 to 1040. Mabillon tells us that not only was St. Helias a most distinguished musician, but that he was "the first to introduce the Roman chant to Cologne,"[1] and he is, most probably, "the stranger and pilgrim" to whom Berno of Riechenau dedicated his well-known musical work, "The Laws of Symphony and Tone."[2] No greater tribute to the esteem in which the Irish monks were held at Reichenau can be cited than the fact that this monastery (founded in 724 by our Irish St. Pirminius) was placed under the patronage of St. Fintan, a Leinster saint, who flourished circa 830. Walafridus Strabo, Dean of St. Gall's, was Abbot of Reichenau from 824 to 849.

The famous Guido of Arezzo (born in 995, and died May 17th, 1050), Benedictine Prior of the monastery of Avellina, perfected the gamut of twenty sounds, and improved diaphony. He devised the hexachordal scale, Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, from the first syllables of the hymn to St. John the Baptist, commencing "Ut queant laxis." It is not a little remarkable that the melody to which this hymn was sung before Guido's time was not an original one, but had been, years before, composed for an Ode of Horace, commencing "Est mihi nonus," and which is to be met with in a Montpellier MS. of the tenth century. This interesting fact strengthens the view put forward in a previous chapter, that many Irish melodies were similarly utilized, or "adapted," by Irish scribes in various copies of the service-books between the eighth and twelfth centuries. Let it not be forgotten that the musical work of St. Ambrose was in great part an adaptation; and, later still, we find the great hymnist, St. Venantius Fortunatus, setting some vintage songs to religious words. Father Michael Moloney, of Bermondsey, some years ago,[3] stated as his "firm belief," that "some day, not far distant, the fact that Gregorian music was largely influenced by ancient Irish music would be satisfactorily established."[4] From all the proofs here quoted—cumulative evidence of the very strongest kind—the reader must be convinced of the deep debt which "plain chant" owes to the monks and scribes of ancient Erin.

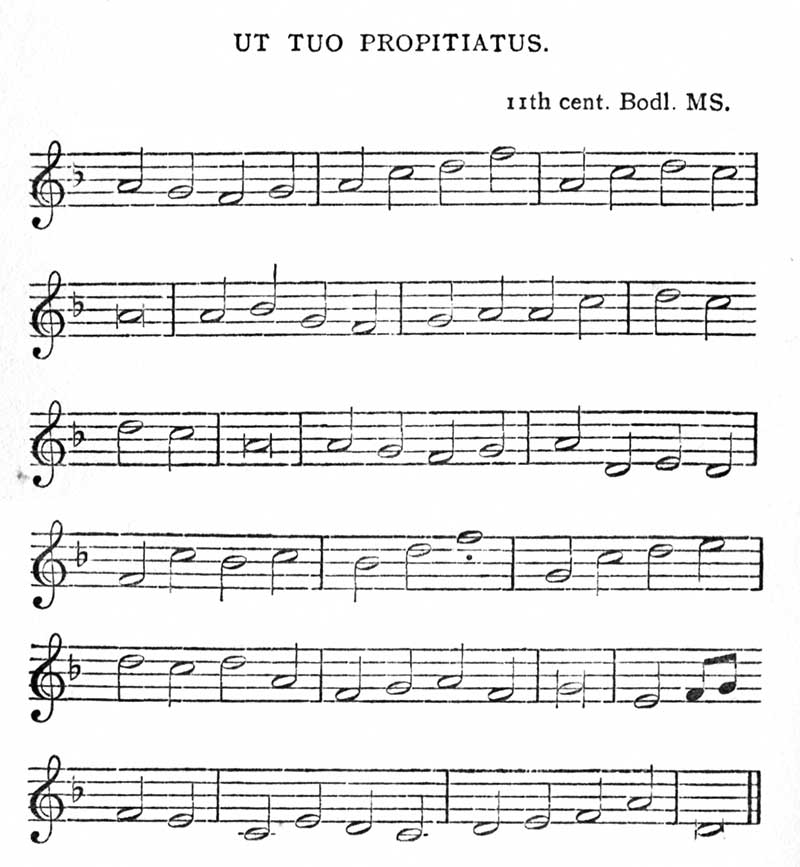

As amply and conclusively supporting my view I can confidently quote the "organised" arrangement of Ut tuo propitiatus, written by an Irish scribe about the year 1095, and interpolated in a tenth century Cornish manuscript now in the Bodleian Library (Bodley, 572). Professor Wooldridge says that it is one of the earliest known examples of "irregular Organum" in contrary movement, employing an independent use of dissonance, and it is written in alphabetical notation. The hymn itself is portion of the hymn to St. Stephen, and apparently was most popular in England, as well as on the continent, as we meet with a variant of it in the Sarum Antiphonal. In 1897, Professor Wooldridge was of opinion that the hymn was of the same age as the whole of the Bodleian manuscript in which it is included, but, in 1901, as a result of closer examination, he agrees with the experts who assign its date as eleventh century, or certainly not later than the year 1100.

The score of the "organal" part, as stated in a learned article by Dr. Oscar Fleischer, in the Vierteljahrsschrift fur Musikwissenshaft, 1890, is really an adaptation, or setting, of "a Gaelic folk song, afterwards worked upon by a learned composer of that period," the melody being "in a scale of the pentatonic character." I subjoin a translated modern version of this ancient Irish melody from the reconstruction as given by Dr. Fleischer:—

In a rare vellum MS. in Trinity College, Dublin (H. 3, 18), compiled about the year 1490, there is an extract given from an Irish tract written at the commencement of the thirteenth century, which exhibits a full knowledge of the Guidonian system, and discusses at great length the etymology of the syllables Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La. A translation of this extract is quoted in lull by Dr. W. K. Sullivan, in his introduction to O'Curry's Lectures. A still more convincing proof that the Guidonian gamut was known in Ireland at the close of the eleventh century is the actual preservation of some Irish airs in Morris's Welsh collection, quoted by Dr. Burney, which are said to have been transcribed in the twelfth century.

The great monastery of St. Peter's, Ratisbon, was established by Muiredach (Marianns) Mac Robertaigh, in 1076; and St. James's, at Ratisbon, was founded in 1090, with Diuma, or Domnus, a monk from the South of Ireland, as Abbot—being built, according to the Chronicon Ratisbonense, "by funds supplied from Ireland to Denis, the Irish Abbot of St. Peter's, at Ratisbon." By a curious irony of fate, the music school of Ratisbon, originally founded by Irish monks, has been for some years past importing German organists to various Catholic churches in Ireland, whilst Ratisbon itself is the home of the great music publishing establishment of F. Pustet, the printer of various liturgical works used in the Western Church.

END OF CHAPTER V.

Notes

[1] The Annals of Ulster tell us that Donnchad, Abbot of Dunshaughlin, died on a pilgrimage at Cologne in 1027, as also did Eochagan, Archdeacon of Slane, in 1042; and, similarly, Brian, King of Leinster, died there in 1052. Of course, the great musical theorist, Franco of Cologne, must have imbibed some of the Irish traditions as to discant or organum.

[2] Mabillon, Annales Benedictinorum, tom. iv., p. 297.

[3] At the Irish Literary Society, London, on January 25th, 1900, the present writer lectured on "A Hundred Years of Irish Music," when a vote of thanks was proposed by the Countess of Aberdeen, and seconded by Father Moloney, the chair being occupied by Mr. C. L. Graves, in the unavoidable absence of Professor Sir Charles Villiers Stanford.

[4] Professor Dickinson, in his monumental book, The Music of the Western Church (1902), unhesitatingly adopts the view of Gevaert, that "actual adaptations of older tunes and a spontaneous enunciating of more obvious melodic formulas" are the true sources of the earlier liturgical chant.