Duke of Schomberg

Schomberg arrived [8] at Bangor, in Down, on the 13th of August, 1689, with a large army, composed of Dutch, French Huguenots, and new levies from England. On the 17th he marched to Belfast, where he met with no resistance; and on the 27th Carrickfergus surrendered to him on honorable terms, after a siege of eight days, but not until its Governor, Colonel Charles MacCarthy More, was reduced to his last barrel of powder. Schomberg pitched on Dundalk for his winter quarters, and entrenched himself there strongly; but disease soon broke out in his camp, and it has been estimated that 10,000 men, fully one-half of the force, perished of want and dysentery. James challenged him to battle several times, but Schomberg was too prudent to risk an encounter in the state of his troops; and the King had not the moral courage to make the first attack.

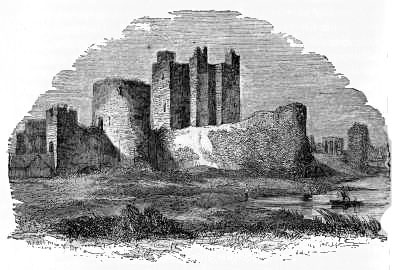

The Castle of Trim

Complaints soon reached England of the condition to which the revolutionary army was reduced. If there were not "own correspondents" then in camp, it is quite clear there were very sharp eyes and very nimble pens. Dr. Walker, whose military experience at Derry appears to have given him a taste for campaigning, was one of the complainants. William sent over a commission to inquire into the matter, who, as usual in such cases, arrived too late to do any good. The men wanted food, the horses wanted provender, the surgeons and apothecaries wanted medicines for the sick.[9] In fact, if we take a report of Crimean mismanagement, we shall have all the details, minus the statement that several of the officers drank themselves to death, and that some who were in power were charged with going shares in the embezzlement of the contractor, Mr. John Shales, who, whether guilty or not, was made the scapegoat on the occasion, and was accused, moreover, of having caused all this evil from partiality to King James, in whose service he had been previously. Mr. John Shales was therefore taken prisoner, and sent under a strong guard to Belfast, and from thence to London. As nothing more is heard of him, it is probable the matter was hushed up, or that he had powerful accomplices in his frauds.

Notes

[8] Arrived.—The journals of two officers of the Williamite army have been published in the Ulster Arch. Jour., and furnish some interesting details of the subsequent campaign. One of the writers is called Bonnivert, and was probably a French refugee; the other was Dr. Davis, a Protestant clergyman, who obtained a captaincy in William's army, and seemed to enjoy preaching and fighting with equal zest.

[9] Sick.—Harris' Life of King William, p. 254, 1719. Macaulay's account of the social state of the camp, where there were so many divines preaching, is a proof that their ministrations were not very successful, and that the lower order of Irish were not at all below the English of the same class in education or refinement. "The moans of the sick were drowned by the blasphemy and ribaldry of their companions. Sometimes, seated on the body of a wretch who had died in the morning, might be seen a wretch destined to die before night, cursing, singing loose songs, and swallowing usquebaugh to the health of the devil. When the corpses were taken away to be buried, the survivors grumbled. A dead man, they said, was a good screen and a good stool. Why, when there was so abundant a supply of such useful articles of furniture, were people to be exposed to the cold air, and forced to crouch on the moist ground?'—Macaulay's History of England, People's Ed. part viii. p. 88.