State of Ireland

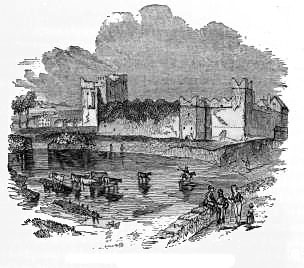

Swords Castle, Dublin

The State of Ireland before and after the Union—Advancement of Trade before the Union—Depression after it—Lord Clare and Lord Castlereagh in the English Parliament—The Catholic Question becomes a Ministerial Difficulty—The Veto—The O'Connell Sept—Early Life of Daniel O'Connell—The Doneraile Conspiracy—O'Connell as Leader of the Catholic Party—The Clare Election—O'Connell in the English House of Parliament—Sir Robert Peel—George IV. visits Ireland—Disturbances in Ireland from the Union to the year 1834, and their Causes—Parliamentary Evidence—The "Second Reformation"—Catholic Emancipation—Emigration, its Causes and Effects—Colonial Policy of England—Statistics of American Trade and Population—Importance of the Irish and Catholic Element in America—Conclusion.

[A.D. 1800—1868.]

T is both a mistake and an injustice to suppose that the page of Irish history closed with the dawn of that summer morning, in the year of grace 1800, when the parliamentary union of Great Britain and Ireland was enacted. I have quoted Sir Jonah Barrrington's description of the closing night of the Irish Parliament, because he writes as an eyewitness, and because few could describe its "last agony" with more touching eloquence and more vivid truthfulness; but I beg leave, in the name of my country, to protest against his conclusion, that "Ireland, as a nation, was extinguished." There never was, and we must almost fear there never will be, a moment in the history of our nation, in which her independence was proclaimed more triumphantly or gloriously, than when O'Connell, the noblest and the best of her sons, obtained Catholic Emancipation.

The immediate effects of the dissolution of the Irish Parliament were certainly appalling. The measure was carried on the 7th of June, 1800. On the 16th of April, 1782, another measure had been carried, to which I must briefly call your attention. That measure was the independence of the Irish Parliament. When it passed, Grattan rose once more in the House, and exclaimed: "Ireland is now a nation! In that new character I hail her, and bowing to her august presence, I say, Esto perpetua!"

A period of unexampled prosperity followed. The very effects of a reaction from conditions under which commerce was purposely restricted and trade paralyzed by law, to one of comparative freedom, could not fail to produce such a result. If the Parliament had been reformed when it was freed, it is probable that Ireland at this moment would be the most prosperous of nations. But the Parliament was not reformed. The prosperity which followed was rather the effect of reaction, than of any real settlement of the Irish question.

The land laws, which unquestionably are the grievance of Ireland, were left untouched, an alien Church was allowed to continue its unjust exactions; and though Ireland was delivered, her chains were not all broken; and those which were, still hung loosely round her, ready for the hand of traitor or of foe. Though nominally freed from English control, the Irish Parliament was not less enslaved by English influence. Perhaps there had never been a period in the history of that nation when bribery was more freely used, when corruption was more predominant.

A considerable number of the peers in the Irish House were English by interest and by education; a majority of the members of the Lower House were their creatures. A man who ambitioned a place in Parliament, should conform to the opinions of his patron; the patron was willing to receive a "compensation" for making his opinions, if he had any, coincide with those of the Government. Many of the members were anxious for preferment for themselves or their friends; the price of preferment was a vote for ministers. The solemn fact of individual responsibility for each individual act, had yet to be understood. Perhaps the lesson has yet to be learned.

One of the first acts of the Irish independent Parliament, was to order the appointment of a committee to inquire into the state of the manufactures of the kingdom, and to ascertain what might be necessary for their improvement. The hearts of the poor, always praying for employment, which had been so long and so cruelly withheld from them, bounded with joy. Petitions poured in on every side. David Bosquet had erected mills in Dublin for the manufacture of metals; he prayed for help. John and Henry Allen had woollen manufactories in the county Dublin; they prayed for help. Thomas Reilly, iron merchant, of the town of Wicklow, wished to introduce improvements in iron works.

James Smith, an Englishman, had cotton manufactories at Balbriggan; he wished to extend them. Anthony Dawson, of Dundrum, near Dublin, had water mills for making tools for all kinds of artisans; this, above all, should be encouraged, now that there was some chance of men having some use for tools. Then there were requests for aid to establish carpet manufactories, linen manufactories, glass manufactories, &c.; and Robert Burke, Esq., of the county Kildare, prayed for the loan of £40,000 for seven years, that he might establish manufactories at Prosperous. These few samples of petitions, taken at random from many others, will enable the reader to form some faint idea of the state of depression in which Ireland was kept by the English nation—of the eagerness of the Irish to work if they were only permitted to do so.