Irish in America

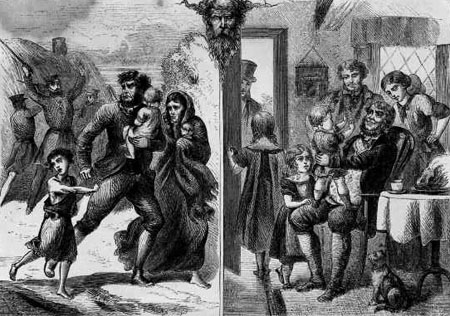

Let those who wish to understand the present history of Ireland, read Mr. Maguire's Irish in America, carefully and thoughtfully. If they do so, and if they are not blinded by wilful prejudices, they must admit that the oft-repeated charges against Irishmen of being improvident and idle are utterly groundless, unless, indeed, they can imagine that the magic influence of a voyage across the Atlantic can change a man's nature completely.

Ireland and America

Let them learn what the Irishman can do, and does do, when freed from the chains of slavery, and when he is permitted to reap some reward for his labour. Let him learn that Irishmen do not forget wrongs; and if they do not always avenge them, that is rather from motives of prudence, than from lack of will. Let him learn that the Catholic priesthood are the true fathers of their people, and the true protectors of their best interests, social and spiritual. Let him read how the good pastor gives his life for his sheep, and counts no journey too long or too dangerous, when even a single soul may be concerned.

Let him judge for himself of the prudence of the same priests, even as regards the temporal affairs of their flocks, and see how, where they are free to do so, they are the foremost to help them, even in the attainment of worldly prosperity. Let him send for Sadlier's Catholic Directory for the United States and Canada, and count over the Catholic population of each diocese; read the names of priests and nuns, and see how strong the Irish element is there. Nay, let him send for one of the most popular and best written of the Protestant American serials, and he will find an account of Catholics and the Catholic religion, which is to be feared few English Protestants would have the honesty to write, and few English Protestant serials the courage to publish, however strong their convictions.

The magazine to which I refer, is the Atlantic Monthly ;the articles were published in the numbers for April and May, 1868, and are entitled "Our Roman Catholic Brethren." Perhaps a careful perusal of them would, to a thoughtful mind, be the best solution of the Irish question. The writer, though avowing himself a Protestant, and declaring that under no circumstances whatever would he be induced to believe in miracles, has shown, with equal candour and attractiveness, what the Catholic Church is, and what it can do, when free and unfettered. He shows it to be the truest and best friend of humanity; he shows it to care most tenderly for the poor and the afflicted; and he shows, above all, how the despised, exiled Irish are its best and truest supports; how the "kitchen often puts the parlour to the blush;" and the self-denial of the poor Irish girl assists not a little in erecting the stately temples to the Almighty, which are springing up in that vast continent from shore to shore, and are only lessened by the demands made on the same willing workers for the poor father and mother,, the young brother or sister, who are supported in their poverty by the alms sent them freely, generously, and constantly by the Irish servant-girl.