Shipbuilding - Story of Belfast

WHEN Queen Elizabeth received her first report of Belfast from her Lord Deputy in the year 1538, he mentioned that it seemed a very suitable place for shipbuilding, and many people think so still. In 1663, small vessels were built in or near Belfast, vessels from six to twelve tons and manned by two or three men.

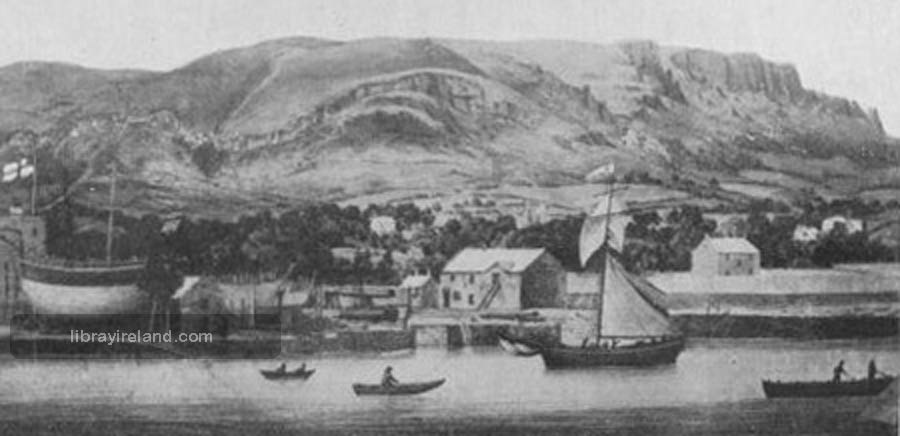

A great and exceptional effort was made a few years before that time. When the Presbyterians were persecuted and ordered to leave the country in the year 1636, a ship was built for them of 150 tons. It sailed for America, but was driven back by adverse winds and "The Eagle's Wing " was obliged to land her passengers in Scotland. We next read of a great stride in shipbuilding, when the "Loyal Charles" of 250 tons was built and launched. Shipbuilding was almost dead when William Ritchie arrived in Belfast. He improved matters very much, and saved both time and expense by repairing vessels here, for formerly they had to be sent away. He visited Belfast in March, 1791, and returned in July of the same year. Ritchie had quickly grasped the future possibilities of shipbuilding in Belfast, so he gave up the yard in Saltcoats and began work here. He brought ten men, apparatus and materials. His brother was an apprentice, and received one third of the business profits until 1793 when they dissolved partnership. He died in 1807, but his work was continued by another brother, John.

William built ships from 50 to 450 tons burden, and John was also successful. There were only six jobbing ship-carpenters in Belfast when he came here. There was no head to direct them, and they had frequently long spells of idleness. Vessels were built and repaired in England and Scotland, but William Ritchie brought with him joiners, blockmakers and blacksmiths. The best work was done in his own shop. He cast anchors of all sizes up to 14 cwt. He did a wonderfully progressive work, he reclaimed land from the sea, embanked it and fronted the quays with stone for his own shipyard, and his graving dock held three vessels of 200 tons. He paid in wages £120 a week, considered a large sum in those days. He engaged to build a dock for the Ballast Office, which occupied four years and was finished in the year 1800. It was known as Ritchie's Dock for many years. His ships for the West Indies and for trading were built of oak, and it was said that "for elegance of mould, fastness of sailing, and utility in every respect they are unrivalled in any of the ports they trade to." This was written of the Belfast-built ships in the year 1811, and the same words might be used again in the year 1913.

Ritchie and McLaine introduced steam navigation, and they built the first steamship in Ireland. William Ritchie retired from business ten years before his death. His shipyard was beside the Harbour Office, and a remnant of the old smithy still exists at the entrance to the tile yard of Messrs. W. D. Henderson & Co., between the Harbour Office and the graving docks.

His business was afterwards carried on by Charles Connell & Sons. The last survivor of this firm—Alexander—was well known, and is still remembered as a great sportsman. Alexander McLaine, who was also a Scotchman, married a daughter of John Ritchie, and the firm was carried on as Ritchie & McLaine, and later on as Alexander McLaine & Sons. This firm existed until the year 1879. The family of McLaine was well known, and most highly respected in Belfast for a great number of years.

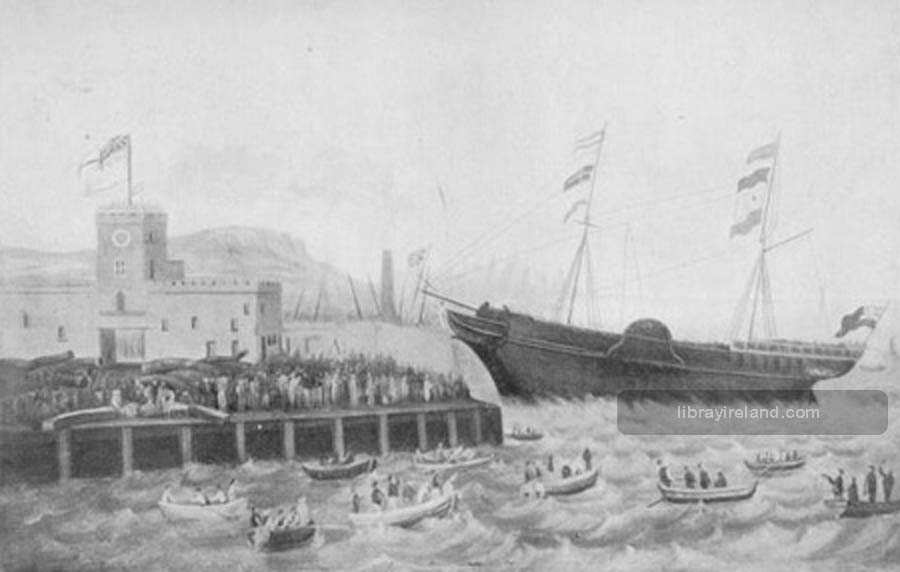

The first steamship that was seen in Belfast was a Scotch boat called the Rob Roy, and she excited great curiosity in the year 1819 when she plied between Belfast and Glasgow. Ritchie built the Chieftain and the engines were made in the Lagan Foundry. It was built for George Langtry, a member of a well-known Belfast family, and it was used as a passenger boat to Liverpool in 1826. Another, the Erin, had the unheard-of audacity of attempting to go to London, and actually ventured on the hazardous journey, but alas! for good intentions, she was lost at the Isle of Man. The first iron boat was built in 1838, which was a wonderful step from the wooden ships. She was built in the yard of the Lagan Foundry. In the same year Ireland had the honour of sending out the first steamboat that ever crossed the Atlantic Ocean. She was owned by the City of Dublin Steamship Company. The Royal William crossed to America in nineteen days, and returned in fourteen and a half. There was a scene of the wildest excitement when the Royal William left the quay in Liverpool. Thousands of people lined the pier to see the venturesome vessel set out on her perilous voyage. The enthusiasm was unbounded, and she left the Mersey amid frantic excitement, loud cheering and cannon firing at many points.

In the year 1853, part of the Queen's Island was taken by Robert Hickson & Company for a shipbuilding yard, the beginning of that work on the County Down side of the river. We may here say a word about the Queen's Island. It was formed of slob-land which was thrown up when the new channel was formed under the superintendence of the engineer, Mr. William Dargan. For many years it was known as "Dargan's Island," but after Queen Victoria's visit to Belfast in 1849, the name was changed to the "Queen's Island." It was the first People's Park, and was for agreat number of years a fine outlet for holiday makers. There was a large glass building, resembling a miniature Crystal Palace, containing a winter garden and a small Zoo. The outside gardens were very well planted, and tastefully arranged. A long row of bathing boxes occupied one side of the Island, and they were used by many people. It was a pleasant holiday resort, and was open to all who paid one halfpenny to be ferried across the river, so the outing combined the excitement of a sea voyage with a rest afterwards on one of the seats under the pleasant shade of the trees. At the North end, there was a battery with cannon mounted, which were used on very special occasions of public rejoicing, until on one hapless day one of them burst, and so the salutes were stopped. Except the name and the memory, nothing now remains of the once well-known pleasure grounds. In the year 1859, Mr. E. J. Harland came to Belfast, and he changed the map.

Mr. G. W. Wolff joined him in 1861, and since then their success has simply been a world's wonder. It is amusing to look back and remember now that, in those early days when these two young men first entertained the idea of shipbuilding, they went to Liverpool to look for land. The Harbour authorities there received their overtures very coldly, considering that they were too young for such a serious undertaking. We must really pardon the Liverpool Harbour Board for such a very natural mistake, as they were then both in their early twenties. So they returned to Belfast, and it is highly probable that the Liverpool authorities may have lived to regret their mistake. However, their loss was most assuredly Belfast's gain. They at first employed 150 men in the year 1861, and built one ship at a time. Now, fifty years after, 14,500 men have constant employment, and their wages bill is £23,000 every week. The largest ships in the world are built and launched here, and the last two cost three millions.

The Titanic and Olympic were marvellous creations. It was a tremendous stride in fifty years to send out a vessel of 45,000 tons, and the Olympic's anchor alone weighs forty tons.

Sir Edward Harland's statue adorns the front of the City Hall, a handsome alert figure and a striking likeness of one of the finest citizens we ever had.

In 1879, Workman and Clark commenced shipbuilding on the County Antrim side of the river, and they also have been wonderfully successful, and their turn-out of work in the year runs the Queen's Island very close indeed. There has been recently added to Harland and Wolff's a great engineering work in the new gantries, the largest in the world. They are so immense in height and size that they are visible for miles. One cost £120,000 and the other £80,000.

The latest electric floating crane is a wonderful piece of mechanism, for it can lift 250 tons with as much ease as a schoolboy lifts an apple. The yards and workshops cover an extent of eighty acres, and every department is full of interest. In the other three great industries, women find employment, thus not leaving the labouring oar entirely in one hand, but in the Queen's Island there is no room for any work but men's.

What would all these men do if we had not the largest and finest ships in the world to carry our produce to the remotest parts of the earth? So these four immense industries are really blended together, and our Belfast tobacco, ropes and linen cross the seas in our swift-sure Belfast ships, carrying our commerce all the wide world over. What would some of the early pioneers think or say if they could revisit Belfast as it is to-day? Imagine William Ritchie standing on the Alexandra Dock, and looking at the Olympic. His feelings might be too deep for words, but his thoughts would be worth recording. After all, perhaps it is as well the early pioneers sleep well where the busy whirr of the looms and clanging of the hammers cannot disturb their well-earned rest. Their work and their names are held in honoured remembrance.